Shuimu

Shuimu (Chinese: 水母), or Shuimu Niangniang (Chinese: 水母娘娘), is a water demon, spirit or witch of Buddhist and Taoist origin in Chinese mythology.[1] She is also identified with the youngest sister of the transcendent White Elephant (Buddha’s gate-warder).[2] According to Chinese folklore, she is responsible for submerging Sizhou (an ancient Chinese city located in today’s Anhui Province) under the waters of Hongze Lake in 1574 A.D. and is currently sealed at the foot of a mountain in Xuyi District.[3] However, different tales of Shuimu exist in different regions of China. For example, in Suzhou, Anhui she may be a demon goddess,[3] while in Taiyuan, Shanxi it is believed that she was a women who was gifted a magical whip by an old man.[4] In Mandarin, the word "Shui" means 'water', "mu" is 'mother', and "niangniang" may mean a goddess. Shuimu is also referred to as The Old Mother of Waters,[3] Fountain Goddess,[4] and Sea Goddess.[5]

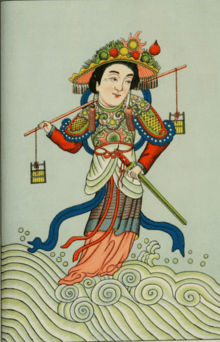

Appearance

She has been described in some sources as a woman who can turn into a snake or dragon. According to Henri Dorés "Researches into Chinese Superstitions", in her ‘human’ form she carries a sword along with two buckets and has black hair with a youthful appearance.[6]

Mythology

The Old Mother of Water

According to Chinese folklore, Shuimu inundated Sizhou yearly and so on the insistence of the locals, Yu Huang or the Jade Emperor raised an army to capture Shuimu and deprive her of her powers. The water demoness, however, was able to trick the army and escape after which she continued to wreak havoc upon the city. One day Shuimu was carrying two buckets of water near the city gate. Li Laojun (a famous philosopher from Dao that takes on a mythological personification here) suspected that she was going to attack Sizhou so while she was away, he led a donkey to the buckets and allowed it to drink the water. However, the donkey was unable to finish all the water as the buckets contained the sources of the five great lakes. Shuimu saw through Li Lao's scheme and overturned one of the buckets with her foot creating a massive flood which submerged the city.[3]

The magic vermicelli

The tale of the magic vermicelli is a continuation of the story after Shuimu had submerged the city of Sizhou. The Monkey King tried to capture her but she continued to slip through his fingers and so asked Guanyin (the Goddess of Mercy and also the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara)[7] for help. Shuimu was famished after being constantly chased so she went to a vermicelli stand where Guanyin (disguised as a woman) was waiting for customers with two bowls of food. However, while she ate, the vermicelli in her stomach turned into iron chains with the end protruding from her mouth. The remaining contents of the bowl also became chains and welded themselves to the end of the ones in her mouth after which she surrendered. Guanyin then ordered The Monkey King to chain Shuimu in a well at the foot of a mountain in Xuyi District. It is believed that the end of her chain can still be seen when the water is low.[3]

Battle against the celestial warriors

In another tale (documented by Henri Doré) Shuimu fought alongside Tuhuogui (a fiery demon) against Wang Lingquan (The supreme God of Taoists) and his army (the celestial warriors) at the request of the Water Elephant. She arrived with five thousand sailors, her magic tortoises, and crabs from the Eastern seas. Despite, Wang Lingquan’s warnings, she and Tuhuogui attacked with water and fire torrents respectively. Shuimu also created large tidal waves from the five great lakes that swept over the plains. However, reinforcements for the celestial warriors arrived and Shuimu was overpowered. The Red Child demon heated her water to the boiling point and so she along with her troops fled to a place called Sizhou) after which Wang and his army won the battle.[6]

The magic whip

There are different legends about Shuimu depending in different region of China. In Shanxi, the story goes that a peasant women was given a magical whip by an old man. Whenever she needed water, she would simply knock her jug with the whip and immediately water would spring out from it. However, her mother-in-law found out about the whip and tried to do the same thing herself, only this time, the water did not stop flowing and the area became the spring Nanlao Quan (难老泉), a source of the Jin River (晋河).[4] At the Jinci temple complex above Nanlao Quan in Taiyuan, one of the temples is dedicated to Shuimu, Shuimu Lou temple (水母楼), was built in the 17th century. The Shuimu Lou temple is a two-storied structure containing a statue of Shuimu.[8]

Rainbow Bridge Shuimu (虹桥水母)

“Presenting the gift of a pearl at the rainbow bridge” or Hongqiao Zengzhu, is a Chinese play in which Shuimu is a demoness that lives under the Rainbow Bridge. The bridge is also close to Sizhou and she calls herself ‘Granny Water Mother’. She rules over other demons and one day meets a young man while she is in town (Sizhou). She falls in love with him and invites him into her underwater residence. The man follows her inside willingly despite knowing that she is a demoness. Once there, he sees the ‘water-repellent pearl’ on her collar and so he gets her drunk, takes the collar and flees. In retaliation, Shuimu drowns Sizhou. Guanyin hears the plight of its people and gathers an army to fight Shuimu, however she does not relent. As a result, Guanyin tricks her into eating noodles that turn into chains while they are in her stomach so she surrenders.[9]

Notes

- Fontenrose, Joseph Eddy. Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins. University of California Press, 1959. Print.

- Doré, Henri. Researches into Chinese Superstitions. Vol 9. Túsewei Printing Press. Internet Archive. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

- Werner, Edward Theodore Chalmers (1922). Myths and Legends of China (PDF). Courier Corporation. pp. 166–168.

- Hoevels, Fritz Erik (1999). Mass Neurosis Religion: Colleted Essays about the Psychoanalysis of Religion. Ahriman-Verlag GmbH. pp. 196–197.

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda (2015). "Chapter 6, Chapter 13". The Encyclopedia of Amazons: Women Warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Era. Open Road Media.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Doré, Henri. Researches into Chinese Superstitions. Vol 9. Túsewei Printing Press. Internet Archive. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda. The Encyclopedia of Amazons: Women Warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Era. Open Road Media, 2015. Print

- "五一山西中线游记(一)——晋祠".

- Yü, Chün-fang. Kuan-Yin: The Chinese Transformation of Avalokitesvara. Columbia University Press, 2001, www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/yu--12028. Page 121

Bibliography

- Buckhardt. Chinese Creeds and Customs. Routledge, 2013. Print. Page 166

- Doré, Henri. Researches into Chinese Superstitions. Túsewei Printing Press. Internet Archive. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

- Fontenrose, Joseph Eddy. Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins. University of California Press, 1959. Print.

- Hoevels, Fritz Erik. Mass Neurosis Religion: Colleted Essays about the Psychoanalysis of Religion. Ahriman-Verlag GmbH, 1999. Page 197

- PhD, Patricia Monaghan. Encyclopedia of Goddesses and Heroines: Revised. New World Library, 2014. Print. Page 70

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda. The Encyclopedia of Amazons: Women Warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Era. Open Road Media, 2015. Print. Chapter 6, Chapter 13

- Werner, Edward Theodore Chalmers. Myths and Legends of China. Courier Corporation, 1994. Print. Page 222