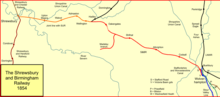

Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway

The Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway was authorised in 1846. It agreed to joint construction with others of the costly Wolverhampton to Birmingham section, the so-called Stour Valley Line. This work was dominated by the hostile London and North Western Railway, which used underhand and coercive tactics. The section between Shrewsbury and Wellington was also built jointly, in this case with the Shropshire Union Railway.

The S&BR opened from Shrewsbury to its own Wolverhampton terminus in 1849. The Stour Valley Line was still delayed by the LNWR, but the S&BR eventually got access to it in 1852. By this time it was obvious that the LNWR was an impossible partner, and the S&BR allied itself to the Great Western Railway, which reached Wolverhampton in 1854. The S&BR merged with the GWR in 1854. With the S&BR and other absorbed railways, the GWR obtained a through route between London and the River Mersey at Birkenhead, and to Manchester and Liverpool by the use of running powers.

The S&BR route was an important part of this main line until the 1960s, when electrification of former LNWR routes compelled concentration of long-distance traffic elsewhere, and the line became a secondary route, still in important passenger operation.

The S&BR line had the distinction of having at one time the northernmost section of GWR broad gauge usage, and much later the first section of the former GWR to have overhead electrification.

Origins

Local people proposed a railway from Birmingham to Shrewsbury by way of Dudley and Wolverhampton in 1844. The London and Birmingham Railway was engaged at the time in competitive rivalry with the Grand Junction Railway and hoped that the Shrewsbury line might enable them to by-pass the GJR; accordingly they supported it, and provisionally agreed a lease.[1][2]

In their own defence, the Grand Junction Railway devised a scheme for a railway from Wolverhampton to Shrewsbury as well as a line from Stafford, on their own main line, to join it. It was these lines that went to the 1845 session of Parliament as the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway, but the scheme failed Standing Orders and was rejected.

Shortly afterwards the London and Birmingham Railway and the Grand Junction Railway amalgamated, forming (with the Manchester and Birmingham Railway)the London and North Western Railway. This changed the competitive situation completely, and both factions within the LNWR abandoned their support for any Shrewsbury line.[1][3]

The independent promoters of the Shrewsbury line called their line the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway. They decided to continue their attempt, but to leave the section of route between Birmingham and Wolverhampton to be built jointly with others: this was going to be the most expensive section to build, and the bigger railways already had plans for the district. That became the Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Stour Valley Railway; it would be paid for jointly, with the S&BR, the LNWR and the Birmingham Canal each subscribing a quarter of the capital; the remaining quarter would come from ordinary public subscriptions.[2]

Authorisation

The Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway bill (now for a railway between Shrewsbury and Wolverhampton only, under 20 miles) and the Stour Valley Railway (the short form name of the BW&SVR) both went to the 1846 session; so did the Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Dudley Railway, destined to be the saviour of the S&BR later on. Sixteen railways in the district were under consideration, and the S&BR capital was £1.3 million. The Stour Valley capital was £1.11 million. The Bills were passed on 3 August 1846.[4][2][5][6]

The Shrewsbury, Oswestry and Chester Junction Railway was authorised in 1845 to build to a terminus in Shrewsbury, but the obvious affinity of that line – it became the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway – with the Birmingham company led to the decision to have a joint station at Shrewsbury, at a modified location. It would also be jointly used by the Shrewsbury and Hereford Railway and the Shropshire Union company. It was ready in time for the opening throughout of the S&BR.[7]

So far as the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway was concerned, the ten miles from Shrewsbury to Wellington, about a third of the extent of the line, was to be built and operated jointly with the Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company; that railway was planning a line from Stafford to Wellington, in order to get access to Shrewsbury.

The final laying out of the line was entrusted to William Baker. The directors instructed that the major structures on the line be made suitable for broad gauge track, in case that were to be laid later.[1][8]

In 1847 the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway got approval to build a branch from Shifnal to Madeley, and extend the Coalbrookdale branch to Ironbridge, as well as increasing capital.[9]

The LNWR gathers strength

In the autumn of 1846 the LNWR took a lease of both the Shropshire Union Railway and Canal system, and of the Stour Valley Railway. The S&BR acquiesced in this, having been given assurances about traffic pooling.[8] The LNWR had acquired share of the Birmingham Canal Company, so that the LNWR now had a 50% share of the Stour Valley Railway as well as the lease. Suddenly the LNWR was dominant in the area, and the Shrewsbury and Birmingham saw that its position was precarious. However an agreement was reached with the LNWR that traffic would not improperly be diverted away from the S&BR line, and the LNWR's Bill to authorise the lease was allowed to pass. The Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway was also given running powers over the Stour Valley line; and in addition that the short section of line from Wolverhampton station to the divergence of the Shrewsbury and Stafford lines would be joint. The running powers would lapse if the S&BR were taken over by the GWR or certain companies considered to be its allies.[10][8]

Opening of the line

Oakengates tunnel, 471 yards, took some time to complete; although it was short, it was to be bored through solid rock.[9]

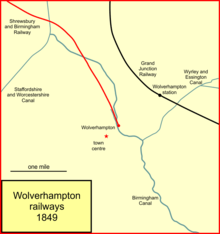

The S&BR opened its line as far as from Shrewsbury to Oakengates station, as well as the joint line on 1 June 1849. The LNWR opened its line from Stafford, joining the joint line at Wellington, on the same day. The rest of the S&BR through to a temporary station at Wolverhampton was opened on 12 November 1849. The Wolverhampton station was a small affair immediately south of the Wednesfield Road. It was at this stage not connected to any other railway, so one platform was enough for the passenger business.[11][12][9]

War with the LNWR

At this period the LNWR decided to do all it could to harm the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway, and its natural allies the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway, and the Chester and Birkenhead Railway. This extended to illegal acts; the worst of these took place around Chester, involving the two railways that opposed the LNWR there.[13] Further south the LNWR engaged in a price war, in which fares dropped to unreasonably low levels, in an attempt to coerce the S&BR.

In addition the LNWR as the major shareholder in the Stour Valley line ensured that the completion of the line, on which the S&BR relied, was delayed. The agreement about traffic pooling was ignored. The LNWR had the old Grand Junction Railway station at Wednesfield Heath, a mile or so from Wolverhampton, while the S&BR connected into no other line at Wolverhampton.[14][15]

Obviously the S&BR was unable to convey goods traffic for points south of Wolverhampton because of LNWR intransigence, and they tried to construct a goods transhipment location alongside the canal at Victoria basin, just north of Wolverhampton, in April 1850. This was alongside their passenger terminus. As they attempted to lay boards to make a pathway for the physical transfer of goods from their wagons to canal barges, they suffered from LNWR physical violence and intimidation there too.[9]

The S&BR was alienated from the LNWR, and turned to the Great Western Railway, which was building its own line towards Wolverhampton.[note 1] On 10 January 1851 a traffic agreement was concluded between the S&BR and the S&CR with the GWR.[16][17][18]

LNWR actions included packing shareholders’ meetings with nominees, the forging of a S&BR company seal, and numerous other improper procedures. As the S&BR and S&CR became increasingly aligned to the GWR, LNWR aggression turned to the Birkenhead, Lancashire and Cheshire Junction Railway. Nevertheless, in 1851 the Associated Companies (the GWR, the S&BR and the S&CR) obtained running powers over the BL&CJR, giving them ultimately access to Birkenhead, Liverpool and Manchester.[19]

Stour Valley line

The Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway needed the Stour Valley line to be opened, to give them access to Birmingham. It was evidently physically completed, but the LNWR now adopted underhand tactics to delay opening that would permit the S&BR trains to run on the line. The escalation of this culminated in the S&BR deciding to run a train on 1 December 1851, despite the LNWR prevarication. The LNWR put physical obstructions on the lie to prevent the train running; a large number of men on both the S&BR and LNWR sides were present, but the planned run was frustrated.

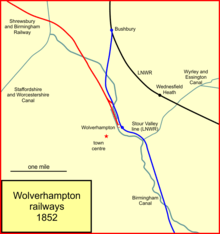

The matter dragged on, with alleged unsafe factors on the line being used to delay opening, in some cases assisted by the Board of Trade inspector. At length the line opened on 1 July 1852. The LNWR was still able to prevent the S&BR trains running, by failing to agree operating rules at Wolverhampton and Birmingham stations, and numerous other artificial difficulties. Eventually on 4 February 1854 S&BR Trains started to run on the Stour Valley Line to Birmingham.[20][21][22][9]

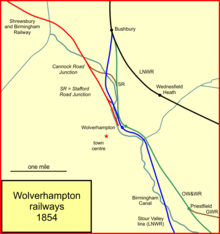

A GWR route at last

The opening of the Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Dudley Railway in 1854 finally gave the S&BR access southwards to the GWR, and the LNWR was at last powerless to frustrate the S&BR in the Birmingham area.[17] The Wolverhampton Junction Railway was an essential part of the connection. It was three-quarters of a mile long and connected the southward course of the S&BR at Stafford Road Junction into the Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Dudley Railway, at Cannock Road Junction. It was wholly owned by the Great Western Railway.

Its course passed through the S&B locomotive and carriage works at Stafford Road; this was quite new, and many modern buildings were demolished to make way for the new connecting line. It opened in on 14 November 1854, at the same time as the BW&DR. It was mixed gauge; OW&WR broad gauge trains required access to Victoria Basin, and the headshunt into the Basin sidings was the northernmost point of the GWR broad gauge.[23]

Amalgamation with the GWR

The determined hostility of the LNWR naturally led to a strong feeling of allied interests between the Great Western Railway, the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway and the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway, and they became known as the Allied Companies. It was clear that formal amalgamation was inevitable, and this was enacted on 7 August 1854, taking effect in 1 September 1854.[24] The two Shrewsbury lines were narrow (standard) gauge and were referred to as the “northern division” within the enlarged GWR. There was no physical connection at first until the Wolverhampton line was opened in November 1854.[25][26]

The Shrewsbury lines which the GWR now absorbed were not greatly profitable; and they had huge indebtedness in debentures and guaranteed preference shares. The two lines together had £3 million of capital, of which only £1.8 million was in ordinary shares. There was half a million in 8% preference shares.[27]

Madeley and Lightmoor

The Lightmoor branch was authorised in S&BR days, to serve a mineral district. It opened in 1854 and was extended to Coalbrookdale in 1864, and the area was connected from the southern end also. The passenger service was never successful and closed in 1915. There was pressure locally to revive it, and remarkably a trial was arranged in 1925; it was unsuccessful and the service closed again two months later.

From 1969 the branch handled merry-go-round services to a coal-fired power station at Ironbridge. This work has ceased and the branch has closed.[28]

In GWR days

In 1858 the GWR built a large goods depot at Herbert Street, Wolverhampton, near the Victoria Basin. In broad gauge days it was used as the transshipment shed at the break of gauge.

GWR passenger trains now used their own station at Wolverhampton, and in March 1859 the GWR sold its half share of the other (High Level) station, inherited from the S&BR, to the LNWR. The connection from the S&BR lines to the High Level station was then severed. Herbert Street depot was alongside that connection, and now traffic for Herbert Street accessed the depot by a one-mile connection from Stafford Road Junction.[29]

From 1854 the Great Western Railway had a through route from Paddington to the Mersey at Birkenhead., albeit with a break of gauge at Wolverhampton. By this time it was obvious that extension of the broad gauge north of Wolverhampton was impossible, and the GWR progressively converted the broad gauge southward to mixed gauge. From 1 October 1861 narrow gauge trains ran between Paddington and Birkenhead.

The S&BR route proved to be an important part of the GWR connection with Birkenhead, and through expresses from London were booked on the route. Local traffic was never significant, and the development of reliable bus services in the 1920s and later took much traffic away from the line.

Oxley marshalling yard was developed just north of the divergence from the Stafford line, and a large carriage servicing depot was later established there.

After 1930

_Market_Drayton_Junction_geograph-2575835-by-Ben-Brooksbank.jpg)

The GWR operated the line as an important main line; Birkenhead was a key access point for Liverpool passenger traffic, and trunk express trains, including a night sleeping car train ran. The Birkenhead, Lancashire and Cheshire Junction Railway network gave direct access for goods trains to Liverpool and Manchester. The BL&CJR was now owned jointly by the GWR and the London, Midland and Scottish Railway as successor to the LNWR. Birkenhead was itself a key destination for coal and an originating point for imported iron ore. As holiday and leisure traffic developed the seasonal train service included through trains to the coastal destinations of Aberystwyth, Barmouth and Pwllheli.

The main line railways of Great Britain were nationalised in 1948, but the train service pattern remained largely unchanged for some time. However a changed pattern of leisure and holiday travel led to a gradual decline of those services, while the local passenger trains suffered a steep decline in patronage. The loss of heavy industry resulted in diminished mineral traffic; and the common ownership of alternative routes led to diversion of much trunk freight to other lines.

From 1966

The Stafford – Wolverhampton – Birmingham line was electrified in 1966. The Paddington to Birkenhead trunk passenger route was ended in 1967, with all through traffic from London to Crewe and beyond being handled over the former LNWR route. Wolverhampton Low Level, the GWR station, was closed to passengers on 6 March 1972[30] and all Wolverhampton passenger traffic was dealt with at the High Level (former LNWR) station. This required reinstatement of the short connecting line to the S&BR line near Stafford Road. Wolverhampton Low Level station was later used as a parcels concentration depot, from 6 April 1970.[31]

Oxley Sidings had become an important carriage servicing depot, and the line from there to Wolverhampton High Level was electrified in 1972. This was the first section of the former GWR to be electrified with overhead equipment.[29][32]

From 1967 development of a new town named Telford took place. The town has a station on the S&BR line, opened in 1986.

In 1983 a new spur line was built at Wolverhampton, enabling direct running from the Stafford direction to Oxley Carriage Sidings: from Stafford Road Junction to Bushbury Junction. The short line was largely built on the course of the Wolverhampton Railway connection from Stafford Road Junction, and a former gas works branch near Bushbury Junction. The connection was installed to enable empty coaching stock trains to access Oxley sidings, but there have been occasional instances of diverted passenger trains using the line.

In 2009 a rail freight depot known as Telford International Railfreight Park was opened, partly funded by generous Government grants. However it does not appear to have attracted much traffic.

The present-day (2019) passenger train service consists of typically three trains an hour on weekdays, with some through trains to Aberystwyth and Holyhead.

Location list

Main line

- Shrewsbury; joint station; opened 1 June 1849;

- Abbey Foregate Junction; convergence of Shrewsbury Loop, 1867 onwards;

- Abbey Foregate; opened April 1887; former ticket platform; closed 30 September 1912;

- Potteries Junction; convergence of Shropshire and Montgomeryshire Railway 1866 – 1880;

- Upton Magna; opened 1 June 1849; closed 7 September 1964;

- Walcot; opened 1 June 1849; closed 7 September 1964;

- Admaston; opened 1 June 1849; closed 7 September 1964;

- Market Drayton Junction; convergence of Market Drayton branch 1867 – 1967;

- Wellington; opened 1 July 1849; still open;

- Stafford Junction; divergence of Stafford line 1849 - 1991;

- End of Joint Line;

- Ketley Junction; divergence of Wellington and Severn Junction Railway (later part of Wellington to Craven Arms Railway, 1857 – 1962;

- New Hadley Halt; opened 3 November 1934; closed 13 May 1985;

- Oakengates; opened 1 June 1849; renamed Oakengates West between 1951 and 1956; still open;

- Telford Central; opened 12 May 1986; still open;

- Hollinswood Junction; divergence of Stirchley branch 1908 - 1959;

- Madeley Junction; convergence of Coalbrookdale line; below;

- Shifnal; opened 13 November 1849;

- Cosford Aerodrome Halt; opened for workmen only 17 January 1938; opened to public 31 March 1938; renamed Cosford 1940;

- Albrighton; opened 13 November 1849; still open;

- Codsall; opened 13 November 1849; still open;

- Birches and Bilbrook; opened 1934; renamed Bilbrook 1974; still open;

- Oxley North Junction; divergence of Kingswinford branch 1925 - 1965;

- Oxley Middle Junction; convergence of line from Kingswinford branch 1925 - 1965;

- Oxley Sidings;

- Stafford Road Junction; 1854 divergence to Cannock Road Junction and Wolverhampton GWR station.

- Wolverhampton Stafford Road; opened October 1850; closed July 1852;

- Spur to LNWR 1852 to 1854;

- Wolverhampton ; temporary station at Wednesfield Road; opened 13 November 1849; closed 1 December 1851, when LNWR station (later High Level) opened.

- Wolverhampton; opened 1 July 1854; closed 6 March 1972.

Wolverhampton Junction Railway and Low Level Station

- Stafford Road Junction; above;

- Dunstall Park; opened 1 December 1896; closed 1 January 1917; reopened 3 March 1919; closed 4 March 1968;

- Cannock Road Junction; convergence with former OW&WR line;

- Wolverhampton Low Level; opened 1 July 1854; closed 6 March 1972.

Lightmoor branch

Opened 1854.

Notes

- At this stage the GWR was no closer than Banbury.

References

- E T MacDermot, History of the Great Western Railway: volume I, published by the Great Western Railway, London, 1927, pages 348 to 351

- Keith M Beck, The Great Western North of Wolverhampton, Ian Allan Limited, Shepperton, 1986, ISBN 0 7110 1615 1, page 10

- Rex Christiansen, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 7: the West Midlands, David & Charles Publishers, Newton Abbot, 1973, 0 7110 6093 0, pages 81 to 83

- Christiansen, page 85

- Herbert Rake, The Progress of the Great Western Railway from London to the Mersey, part1, in the Railway Magazine, June 1915

- Ernest F Carter, An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles, Cassell, London, 1959, pages 117 to 119

- MacDermot, page 346

- Beck, page 11

- Rake, part 2, in Railway Magazine, August 1915

- MacDermot, pages 351 to 353

- MacDermot, page 353

- Christiansen, page 86

- Peter E Baughan, A Regional History of the Railways Of Great Britain: volume 11: North and Mid Wales, David St John Thomas, Nairn, 1980, ISBN 0 946537 59 3, pages 40 and 41

- Geoffrey Holt and Gordon Biddle, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 10: the North West, David St John Thomas, Nairn, 1986, ISBN 0 946537 34 8, page 45

- George P Neele, Railway Reminiscences, McCorquodale & Co, London, 1904, pages 28 and 29

- MacDermot, pages 357 to 363

- Christiansen, page 88

- Beck, page 14

- MacDermot, pages 371 to 373

- MacDermot, pages 373 to 380

- Christiansen, pages 88 and 89

- Beck, pages 15 to 18

- Christiansen, pages 91 and 92

- MacDermot, page 390

- MacDermot, page 397

- Donald J Grant, Directory of the Railway Companies of Great Britain, Matador Publishers, Kibworth Beauchamp, 2017, ISBN 978 1785893 537, page 502

- MacDermot pages 402 and 403

- Christiansen, page 156

- Christiansen, page 90 and 91

- Michael Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in England, Scotland and Wales: A Chronology, the Railway and Canal Historical Society, Richmond, Surrey, 2002

- Christiansen, pages 95 and 96

- J C Gillham, The Age of the Electric Train, Ian Allan Limited, Shepperton, 1988, ISBN 0 7110 1392 6

- R A Cooke, Atlas of the Great Western Railway as at 1947, Wild Swan Publications, Didcot, 1997, ISBN 1 874103 38 0

- Col M H Cobb, The Railways of Great Britain: A Historical Atlas, Ian Allan Limited, Shepperton, 2002