Shoulder-in

The shoulder-in is a lateral movement in dressage used to supple and balance the horse and encourage use of its hindquarters. It is performed on three tracks, where the horse is bent around the rider's inside leg so that the horse's inside hind leg and outside foreleg travel on the same line. For some authors it is a "key lesson" of dressage, performed on a daily basis.[1]

History

In the seventeenth century, Antoine de Pluvinel used the basic shoulder-in exercise to increase the horse's suppleness and to get the animal used to the aids, especially the leg aids. He felt the exercise helped to make the horse obedient. Independently, the Duke of Newcastle developed the exercise. In the eighteenth century, the French riding master Francois Robichon de la Gueriniere adapted the movement for use on straight lines.

Performance

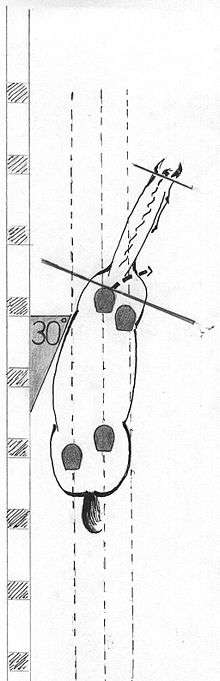

In the shoulder-in, the shoulder of the horse is brought to the inside, creating a 30-degree-angle with the rail, with the neck bent only the slightest amount, only softening in the jaw so that the corner of the eye is visible to the rider. The horse's hind legs track straight forward along the line of travel while the front legs move laterally, with the inside foreleg crossing in front of the outside foreleg and the inside hind hoof tracking into or beyond the hoofprint made by the outside foreleg. Because the horse is bending away from the direction of travel, the movement requires a certain amount of collection. The shoulder-in can be performed at any forward gait, but in dressage competition it is usually ridden only at the trot.

A young horse is first introduced to the movement when coming out of a corner or a circle on which the horse is already correctly bent, from nose to tail, along the arc of the corner or circle, as it is usually easier to maintain bend than to establish it from a straight line in the young or green (untrained) horse.

The rider is positioned on the horse in a manner similar to riding a circle or corner, with the shoulders aligned to mirror the angle of the horse's shoulders, while the rider's hips and legs mirror the position of the horse's hind legs. Thus, as the circle becomes the shoulder-in, the rider's shoulders are turned to the inside, while his/her hips remain "straight" on the track. The rider uses the inside leg at the girth to maintain the bend and encourage the horse to step under its body with its inside hind leg, while the rider's outside leg prevents the horse's haunches from swinging out. The outside rein steadies the horse and helps maintain the correct bend, while the inside rein is used with a giving hand. The rider's back and position in the saddle shift toward the horse's outside shoulder in order to restrain the horse from moving off the track, maintaining movement along the track.

Common errors include use of the inside rein to create the bend for the shoulder-in. Doing so creates too much bend in the horse's neck compared to its body,[2] and may also pull the horse off the track. The inside rein only asks for flexion, and if the horse is correctly on the aids, the inside rein can be loose.

Variants of the Shoulder-In include the Shoulder-fore, where less angle is asked, and a four-track movement is created. This is a useful exercise for the younger horse, and can be used in canter work to negate a horse's natural tendency toward crookedness.

References

- Cf. Loriston-Clarke, p. 84. - Also: "The shoulder-in is a key lesson of advanced dressage training because many features of the correctly ridden horse are represented in this movement.", translated from the German Richtlinien, p. 50.

- "Too much neck bend and no angle" is one of the "common faults". Davison, p. 54.

Sources

- Richard Davison, Dressage Priority Points, Howell Book House, New York 1995, ISBN 0-87605-932-9

- Jennie Loriston-Clarke, The Complete Guide to Dressage. How to Achieve Perfect Harmony between You and Your Horse. Principal Movements in Step-by-step Sequences. Demonstrated by a World Medallist. Quarto Publishing plc London 1989, reprinted 1993, ISBN 0-09-174430-X

- Richtlinien für Reiten und Fahren. Bd. 2: Ausbildung für Fortgeschrittene. Ed. by the German Equestrian Federation (FNverlag) Warendorf 12th edition 1997, ISBN 3-88542-283-2