Short-tailed chinchilla

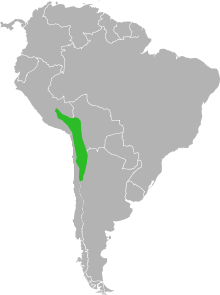

The short-tailed chinchilla (Chinchilla chinchilla;[1][2] formerly C. brevicaudata)—also called the Bolivian, Peruvian, or royal chinchilla—is an endangered species of South American rodent, and one of two species in the genus Chinchilla. Their original native range extended throughout the Andes Mountains of Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Bolivia. These animals were exploited for their luxurious fur, causing their numbers in the wild to dwindle. The other species of chinchilla is also endangered; C. lanigera, or the long-tailed chinchilla, is the wild ancestor of the domestic chinchilla, which is commonly raised as a pocket pet throughout the world.

| Short-tailed chinchilla | |

|---|---|

| |

| A wild Peruvian chinchilla nestling in the rock of the Andes Mountains (2006) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Chinchillidae |

| Genus: | Chinchilla |

| Species: | C. chinchilla |

| Binomial name | |

| Chinchilla chinchilla (Lichtenstein, 1829) | |

| |

| Past range of Chinchilla chinchilla. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Characteristics

Short-tailed chinchillas’ bodies measure between 28 to 49 centimetres (11 to 19 in) long and weigh around 38 to 50 ounces (1,100 to 1,400 g). By comparison, wild long-tailed chinchillas have body lengths up to 26 cm (10 in). Male long-tailed chinchillas weigh 13.0–17.4 ounces (up to 1.09 pounds (0.49 kg)) and females weigh 13.4–15.9 ounces (up to 0.99 pounds (0.45 kg)).[3] Domesticated animals are larger: the female weighs up to 800 g (28 oz) and males up to 600 g (21 oz).

They have short front legs and long, powerful hind legs that aid in climbing and jumping. Short-tailed chinchillas have thicker necks and shoulders, and have shorter tails than their long-tailed relatives by a little over one inch (up to 100 mm (3.9 in) compared to 130 mm (5.1 in)).[4] Domestic chinchillas have tails measuring 3 to 6 inches long.[4]

Ecology

In the wild, chinchillas burrow under rocks or in the ground for shelter. They mostly live in colder climates, for which they are well-adapted because of their dense fur. They feed upon vegetation. They are social animals living in colonies or herds; chinchillas usually have litters of one or two offspring.

Commercialization

Many chinchillas are bred in captivity for their fur, which is very fine and dense, and is in high demand in the fur industry. Commercial hunting began in 1829 and increased every year by about half a million skins, as fur and skin demand increased in the United States and Europe: “[t]he continuous and intense harvesting rate [...] was not sustainable and the number of chinchillas hunted declined until the resource was considered economically extinct by 1917."[5]

Hunting chinchillas became illegal in 1929, but those laws were not effectively enforced until 1983.[5] Domestic chinchillas come from 11 specimens obtained by Mathius F. Chapman in 1923 for the purposes of breeding for the fur trade.[4]

Conservation

Because of an impending extinction of short-tailed chinchillas, conservation measures were implemented in the 1890s in Chile. However, these measures were unregulated. The 1910 treaty between Chile, Bolivia, Argentina, and Peru brought the first international efforts to ban the hunting and commercial harvesting of chinchillas. Unfortunately, this effort led to great price increases, which caused a further decline of the remaining populations.

The first successful protection law, passed in Chile, was not until 1929. Today, both the short-tailed and long-tailed chinchillas are listed as “endangered” by Chile and by the IUCN.[6] Because of successful reproduction in captive environments, chinchillas are less hunted in the wild.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chinchilla brevicaudata. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Chinchilla brevicaudata |

- Roach, N.; Kennerley, R. (2016). "Chinchilla chinchilla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T4651A22191157. Retrieved 30 January 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woods, C. A. and Kilpatrick, C. W. (2005). Infraorder Hystricognathi. In: D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder (eds), Mammal Species of the World, pp. 1538-1599. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, USA.

- Spotorno, Angel E.; Zuleta, C.A.; Valladares, J.P.; Deane, A.L.; Jiménez, J.E. (15 December 2004). "Chinchilla laniger". Mammalian Species. 758: 1–9. doi:10.1644/758. PDF Archived 2010-12-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Animal-World. (2007) http://animal-world.com/encyclo/critters/chinchilla/chinchilla.php. accessed on April 24, 2007.

- Jiménez, Jamie E. (1995) The Extirpation and Current Status of the Wild Chinchillas Chinchilla langigera and C. brevicaudata. Gainesville, FL. PDF

- Jiménez, J.E. 1995. Conservation of the last wild chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera) archipelago: a metapopulation approach. Vida Silvestre Neotropical 4:89-97.