Shireoaks Hall

Shireoaks Hall is a grade II* listed 17th-century country house in the hamlet of Shireoaks, 2 1⁄4 miles (3.6 km) north-west of Worksop, Nottinghamshire, UK.[1]

| Shireoaks Hall | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Country house |

| Address | Thorpe Lane, Shireoaks, Nottinghamshire, England |

| Coordinates | 53°19′10″N 1°10′20″W |

| Construction started | 1612 |

| Completed | 1617 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | John Smythson |

| Designations | Grade II* listed building |

The modestly sized house was originally built for Thomas Hewett, probably by John Smythson (son of Robert Smythson), between 1612 and 1617. It was remodelled around 1700 and further restored in 1812 and again after 1975. It is built of coarse square rubble with a slate roof and stands in a rectangular 40-acre (16 ha), formerly open parkland with avenues of trees, fishponds and a deerpark, which is now enclosed as farmland.[2][3]

The 17th and 18th-century landscaped park that surrounds the hall is Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[4]

History

The estate acquired

The manor of Shireoaks was given to the Priory of Worksop by Emma de Lovetot, whose husband William de Lovetot founded the priory in 1105.[5] The Prior and convent leased the grange to Henry Ellis and his wife Dame Luce in 1458.[6] In August 1546, following the Dissolution of the Monasteries by King Henry VIII, the manor, lordship or grange, with appurtenances in Sherockes, Gytford and Derfold (Darfoulds), was granted to Robert and Hugh Thornhill of Walkeringham with licence to alienate it to Thomas Hewett, Clothworker of London.[7][8][9] At about the same time Thomas Hewett had acquired the (already plundered) house and lands of Roche Abbey at Maltby, South Yorkshire (about 7 miles north of Shireoaks), from which he could have recovered building stone.[10] He kept Roche for 18 years until granted licence to alienate it to Richard Hunt of Manchester in January 1563/64.[11][12]

The brothers William and Thomas Hewett were born in the hamlet of Wales, in Laughton-en-le-Morthen, South Yorkshire, the sons of Edmund Hewett.[13] Around 1530 both became free of the newly-chartered Company of Clothworkers in the city of London. William Hewett the Master of that Company in 1543-1544 (after he had purchased Harthill,[14] and shortly before Thomas purchased Roche and Shireoaks), was Sheriff of London (with Thomas Offley) for 1553-1554 (Queen Mary's first year), and was elected Lord Mayor of London in 1559 (as Elizabeth I's reign was beginning). Sir William died in 1567 making his only daughter (Anne, wife of Sir Edward Osborne) heir to his lands at Wales and Harthill,[15] which became the core of the Kiveton Park estate of their descendants, the Dukes of Leeds.

Shireoaks manor had a special association with the ancient oak woodlands (part of Sherwood) which grew where the counties of Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire met: the precise location was debated, but one enormous tree standing in the 18th century was said to overhang all three.[16][17] In 1576 Thomas Hewett, who became a very prosperous London merchant, died leaving Shireoaks manor to his son Henry, also a citizen Clothworker.[18] Henry's brother William had received the parsonage of Dunton Bassett in Leicestershire, and lands at Mansfield, from his uncle: distinct branches of the family evolved. Henry died in 1598, leaving his "Manour, Lordshippe or Grange of Sherookes" to his eldest son and heir (Sir) Thomas Hewett.[19] The "Grange" refers to the monastic manorial farmstead.

The first Hall

The construction of Shireoaks Hall as a more imposing residence on this site is credited to this Sir Thomas, grandson of the Clothworker Thomas. Before 1619 he conveyed the manor to William Wrottesley, presumably as a marital endowment.[20] The design of the building is attributed to the architect John Smythson, son of Robert Smythson, and the date of the work probably between 1612 and 1617.[21] Old heraldic arms were restored to Sir Thomas in 1618 by Richard St George.[22]

This was a substantial but compact rectangular structure built of Magnesian Limestone, its principal frontages facing south-west, to a prospect of the park and estates, and north-east overlooking a large enclosed rectangular terrace garden on the same lateral alignment, with the course of the river Ryton just beyond. Across the upper terrace next to the house a path aligned on the central axis of the house leads down a flight of steps to the main broad terrace, across this and beyond, to two further flights leading to narrower lower terraces towards the river.[23] The Hall stands midway along the south-western edge of this garden, the perimeter walls enclosing a considerable area of land thought to have been laid out thus in the original phase of construction.[24]

The Sir Thomas Hewett for whom this Hall was built resided at Shireoaks and became Sheriff of Nottinghamshire for 1627. He lived long, through the English Civil War and the Commonwealth of England, and to see his son William Hewett married and the birth of a grandson Thomas Hewett in around 1656. However William died at about the same time as his father (which was in 1660-1661),[25] and so the infant Thomas at four years of age became the heir to Shireoaks. He was taken to Shrewsbury (where his grandfather Sir Richard Prynce the younger (1598-1665) was yet living, at Whitehall mansion[26]) for education, and during his minority the Hall was occupied by the Earle family of Rampton.[27] Having matriculated at the University of Oxford in 1676,[28] in 1677 he leased the Hall for seven years to William and Richard Sanderson of Godford.[29]

Development: park and water-gardens

This younger (Sir) Thomas Hewett, having completed his studies at Oxford, a term of service in the Yeomen of the Guard to Charles II, and some four or five years of travel in Europe, in 1689 married in Geneva and brought his young wife Frances home to Shireoaks.[30] Thomas settled the manor and premises in Shireoaks upon his marriage, by lease and release to Sir Edward Betenson, 2nd Bart., in 1692.[31] He became a noted royal servant and official, Surveyor-General of Woods in 1701 and 1714 and Surveyor of the King's Works from 1719 until his death in 1726.[32] Privately he made extensive alterations and improvements to his house and park at Shireoaks.[33] His wife was a friend and correspondent of the young Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.[34]

In addition to the alterations of c. 1700 to the main house at Shireoaks, various built developments around the Hall were carried out. A matching pair of two-storey rectangular outbuildings with steeply-pitched hipped roofs, now called the East and West Stables (but with domestic fenestration), were built at the north approach to the Hall, the space between them forming an entrance way.[35] Two pools were developed to the north-east of these, enclosing the north-west boundary of the terraced garden. A canal pool, called the "Fountain Pool", was created below the north-east side of the terraces, 127 metres long and 21 metres wide, with a semicircular extension at the centre of the farther side (corresponding to the house axis), presumably the position of a fountain.[36]

- The canal garden

The main extent of the park (now mostly agricultural land) lay south-west of the Hall, between Thorpe Lane to the north, Spring Lane to the east, Steetley Lane to the south and Dumb Hall Lane and Netherhall Lane in the west. Through this landscape Sir Thomas Hewett laid out a formal prospect. A great lawn extended from the south front of the Hall, ending in a ha-ha to exclude livestock from the park without interrupting the view. Beyond this, in line with the central (front-to-back) axis of the Hall itself, he built a garden canal 250 metres long. This was fed from a circular basin 122 metres in diameter situated (on the same line) in a woodland plantation 880 metres from the Hall, itself fed by a 400-metre culvert from Netherhall. Between the basin and the farther end of the canal was created an artificial system of 34 cascades falling through 12 separate pools. Over all this distance was a pathway along the south side and a sheltering line of yew trees interspersed with a single linden tree after every third yew.[37]

- The avenues and pavilion

Two long straight avenues of beech trees were planted on lines opening away symmetrically from the Hall and diverging from the canal as their median axis, so as to frame the Vista (the arrangement called a "patte d'oie"). A third avenue crossed between the further ends, and the woodlands to the north of the basin (Shireoaks Park Wood) and those to the south-west of it (Scratta Wood) formed the distant backdrop to the scene. In Scratta Wood Sir Thomas built a pavilion or banqueting house in Italian style. It was a rectangular structure with flights of steps to entrances at each end. Inside were three rooms with marble walls and floors, each differently appointed with pilasters according to the three classical orders, and with "little Cupids on several Angles prettily design'd".[38] The ceilings were painted by Henry Trench (an Irish historical painter who studied in Italy and died in 1726[39]), and the building housed a bust of Sir Thomas Hewett by John Michael Rysbrack.[40][41] Hewett's banqueting house no longer exists.

- Completion

Hewett also formed or enlarged the deer-park. The works were not entirely complete at his death in 1726: "Whereas I have begun the building of the house in the wood called Scratoe[42] and also have designed to make severall Cutts and other ornaments in and about the said Wood according to a draught and design I have made and drawn thereof", he therefore empowered his trustees to complete the work. He made his widow's lifetime tenure of the hall dependent (among other responsibilities) upon her maintaining there a herd of 200 deer. He asked to be buried in the chancel of the church at Wales, Yorkshire, where he has a monument with an informative inscription.[43]

His widow went to live in London where she died in 1756 aged 88, but she was buried beside her husband in the church at Wales.[44] She is said to have retained her beauty and accomplishments into old age.[45] Her will details her collections of paintings and her tea-sets of blue-and-white and red-and white china.[46] John Hallam, who under Sir Thomas Hewett's regime as Surveyor-General of the King's Works had been Secretary to the Board, and Clerk of Works at Whitehall, Westminster and St James's,[47] shared Hewett's enthusiasm for hydrostatics and designed and built a Bathhouse-Summerhouse for Sir George Savile, 7th Baronet, at Rufford Abbey in 1730.[48]

John Thornhagh Hewett

By Sir Thomas's will his estates including Shireoaks, having been held by his wife, in 1744 came under the administration of his godson John Thornhaugh of Osberton Hall (near Worksop), grandson of John Thornhagh, M.P. and Elizabeth Earle of Stragglethorpe, and son of Saint-Andrew Thornhagh,[49] who was executor to the will but had died in 1742.[50][51] Sir Thomas is said to have dispossessed his own daughter because she had formed a liaison with a fortune-teller.[52] The will named John Thornhaugh as residuary legatee, upon condition that he adopt the surname of Hewett (which he did in 1756[53]). John studied at Queens' College in the University of Cambridge, where he was admitted Fellow commoner in 1739.[54] In that year 1744 he married Arabella (daughter of Sir George Savile, 7th Baronet), who died in 1767:[55][56] their only surviving daughter Mary Arabella married Francis Ferrand Foljambe of Aldwarke in 1774.[57][58]

John Thornhaugh Hewett, M.P. for Nottinghamshire from 1747 to 1774,[59] was also the owner of Osberton Hall, Bassetlaw Wapentake, which had passed to his family in the late 17th century and was let to other residents. He is thought to have been responsible for reshaping the central block of that hall, with its original full-height porch and colonnaded pediment:[60][61] a private Museum was developed there.[62] Through his kinship with the Foljambes and Saviles at Scofton Hall,[63] part of John's extensive correspondence survives.[64] John Hewett was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London by 1771,[65] and received antiquary visitors at Shireoaks during the 1770s.[66] He had his own collections of books and pictures, and a cabinet of foreign medals and coins is particularly mentioned in his will. He died in 1787 without male issue.[67] His wife of his late years (after 1783), John Norris Hewett,[68] survived him and died in Richmond, Surrey in 1790.[69] John (Thornhaugh) Hewett and Arabella are buried at Sturton le Steeple, Nottinghamshire, where both have memorial inscriptions.[70]

Revd. John Hewett

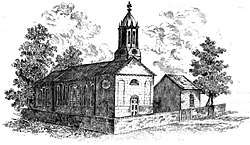

With John Hewett's death in 1787, Shireoaks and other properties passed (under Sir Thomas Hewett's will) to the Revd. John Hewett (1722-1811), as the male heir of his father Revd. John Hewett of Harthill (c.1690-1757). The Duke of Leeds, as lay patron of the church of Harthill (closely in the sphere of Kiveton and Wales), had granted that benefice to his grandfather (John, c. 1664-1715) in 1695, to which his father followed in 1715 and the younger John in 1757.[71][72] He came to the estate of Shireoaks at the age of 65 and enjoyed it for more than 20 years. He built a chapel of ease attached to the estate in 1809: "a neat stone edifice, consisting of a nave and chancel, with an octangular tower surmounted by a cupola."[73] This structure, minus the tower, is now the Shireoaks village hall.

Decline

In 1810 the Revd. John made a deed of gift of the Hall and estate to his relative John Wheatley, reserving his own lifetime occupancy. Wheatley instantly (the same day) re-sold it to Vincent Eyre, agent for Charles Howard, 11th Duke of Norfolk, seated at Worksop. The new owner soon began to cut down the beech avenues, greatly to the Revd. Hewett's mortification, and while he was unable to prevent what had been done he showed in law that the timber was not contained in the sale, and obliged the owner to pay for it. On his last excursion from the hall the old man's carriage was actually obstructed from passing by the felled trees lying across the way. The shock of this devastation brought on his death (aged 89) in 1811.[74] He is said to be buried in his chapel.[75]

The death of the Revd. Hewett was the signal for the Hall itself to be torn down except for that portion of the walls which were bought for a small sum by Mr Froggett, of Sheffield, and fitted up as a dwelling.[76] The Duke's descendants sold it in 1842, together with their Manor of Worksop, to the then Duke of Newcastle. In 1854 the latter Duke's successor discovered a valuable coal seam beneath the land, in time sold much of it to the Shireoaks Colliery Company, and in 1863 built a church for the growing colliery village.[41][77]

In 1945 the hall, by now somewhat dilapidated, was sold to a local farmer. The house and the water gardens have been separately owned since the 1970s.

References

- See: Sheffield City Archives (Arundel Castle Manuscripts): "Shireoaks deeds of the Hewitt family 1577-1659", ref. ACM/65260; "Shireoaks Manor, survey and particular 1600-1650", ref. ACM/W/185. Nottinghamshire Archives (Foljambe collections): "Notts (Shireoaks, etc) deeds and estate papers and Hewett family papers", ref. DD FJ (The National Archives (UK), Discovery Catalogue).

- "Shireoaks Hall, Shireoaks". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- "Nottinghamshire-Bassetlaw-Shireoaks" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-30. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- Historic England, "Shireoaks Hall (1000367)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 2 December 2016

- 'Houses of Austin canons: The Priory of Worksop', in W. Page (ed.), A History of the County of Nottingham, Vol. 2 (V.C.H., London 1910), pp. 125-29 (British History Online).

- R. White, Worksop, "The Dukery" and Sherwood Forest (1875), pp. 82-85 (Internet Archive). Facsimile of the 1458 lease, made 1751, following page 82.

- N. Pevsner, The Buildings of England, 2nd edn. revised by E. Williamson (Harmondsworth, 1979), p. 310. The National Archives, Discovery Catalogue: Conveyance of 1546, Sheffield City Archives, ACM/WD/559, 776, 777.

- J. Throsby (ed.), Thoroton's History of Nottinghamshire: Republished with Large Additions, 3 vols (B. and J. White, London 1797), III, pp. 400-01 (Google).

- 'Grants in August 1546' in J. Gairdner and R.H. Brodie (eds), Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Vol. 21 Part 1: January-August 1546 (HMSO, London 1908), no. 17, p. 762 and no. 35, pp. 767-68 (British History Online).

- '1166. Grants in June, 1546: 73. Licences to alienate', in Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, Vol. 21 Part 1, p. 582 (British History Online).

- E. Milner, ed. E. Benham, Records of the Lumleys of Lumley Castle (George Bell and Sons, London 1904), p. 359 (Internet Archive).

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Elizabeth I, Vol. III: 1563-1566 (HMSO 1960), p. 134, no. 571 (Internet Archive).

- R.E.C. Waters, Genealogical Memoirs of the Extinct Family of Chester of Chicheley, Their Ancestors and Descendants, 2 vols (Robson and Sons, London 1878), I, pp. 226–29.

- Leeds Library, 'Deeds and related documents', YAS/DD5 Duke of Leeds Library Catalogue, ref. DD5/3 passim (Leeds Library pdf)

- Will of Sir William Huett, Alderman of London (P.C.C. 1567). Printed in full in D. Hewett, William Hewett, 1496–1566/7, Lord Mayor of London (Unicorn Publishing, London 2004), pp. 14–24.

- J. Stacye (contributor), 'On the true site of the celebrated Shireoak' (Proceedings), Journal of the British Archaeological Association, XXX (1874), pp. 202-05 (Google).

- J. Evelyn, Sylva: Or, a Discourse of Forest-trees, and the Propagation of Timber in His Majesty's Dominions, Fifth Edition (London 1729), p. 202 (Google).

- Will of Thomas Hewett, Clothworker of Saint Clement Eastcheap, City of London (P.C.C. 1576, Carew quire).

- Will of Henry Hewett, Clothworker of Saint Mary Orgar, City of London (P.C.C. 1598, Lewyn quire).

- 'Pardon to William Wrottesley', Sheffield City Archives, ref. ACM/WD/928 (The National Archives (UK), Discovery Catalogue).

- M. Girouard, Robert Smythson and the Elizabethan Country House (Yale University Press, New Haven 1983), pp. 134-38 and Pls. 74-75. (Original: Country Life 1966).

- J. Foster, ed. W.H. Rylands, Grantees of Arms Named in Doquets and Patents to the End of the XVII Century Harleian Society LXVI (1915: Reprint by The Armorial Register Limited, 2016), p. 123 (Google), citing Harleian MS 1422 fol. 16, and B.M. Add. MS 5524, fol 206.

- 'Gardens and Pleasure grounds', in English Heritage, "Shireoaks Hall", Official Listing.

- N. Pevsner and E. Williamson, The Buildings of England: Nottinghamshire, 2nd Edition (Harmondsworth 1979), pp. 312-13.

- Will (01/12/1659) of Sir Thomas Hewett of Shireoaks, Worksop, Proved Retford Deanery, 13 December 1661: Nottinghamshire Archives, ref. PR/NW 7245 (Nottingham County Council).

- "Will of Sir Richard Prynce, 1666", in H.E. Forrest, 'Wills of the Prynce Family', Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society XLI Part 1 (1921), pp. 122-32, at pp. 126-28 (Society's pdf, at pp. 136-38)

- M. Doole, 'Sir Thomas Hewett, a man of Nottinghamshire and beyond', Thoroton Society Newsletter, Issue 94 (Winter 2018), pp. 4-6 (Thoroton Society online).

- J. Foster (ed.), Alumni Oxonienses 1500-1714 (Oxford 1891), at 'Hawten-Hider', pp. 679-705 (British History Online).

- Agreement of lease (1677), Sheffield City Archives, ref. ACM/WD/797 (The National Archives (UK), Discovery Catalogue).

- J. Holland, The History, Antiquities, and Description of the Town and Parish of Worksop (J. Blackwell, Sheffield 1826), pp. 176-77 (Google).

- University of Nottingham, Manuscripts and Special Collections, Newcastle family of Clumber Park papers, ref. Ne 6 D 2/39/1 (Calm).

- Doole, 'Sir Thomas Hewett', (Thoroton Society online).

- H.M. Colvin (et al.), A History of the King's Works, Vol. V: 1660-1782 (HMSO 1963), pp. 71-73.

- 'Supplement: Letters to Mrs. Hewet', in J. Dallaway (ed.), The Works of the Right Honourable Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Fifth Edition, 5 vols (Richard Phillips, London 1805), V, pp. 225-57 (Google).

- See images in: (HughieD), "Report: Shireoaks Manor, Nottinghamshire, July 2018", 28DL Urban Exploration (28DaysLater.co.uk)

- Historic England Scheduled Monument: List entry number: 1021383 (Listing), 'Formal and water gardens at Shireoaks Hall'.

- Historic England Scheduled Monument: List entry number: 1021383 (Listing), 'Formal and water gardens at Shireoaks Hall'.

- Colvin, History of the King's Works, V, pp. 71-72, citing a description by George Vertue.

- W.G. Strickland, A Dictionary of Irish Artists, 2 Vols (Maunsell and Company, London and Dublin 1913), II.

- (Pevsner and Williamson 1979)

- "Nottinghamshire History: The Dukeries". Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- Sir Thomas's will reads "Scratoe" in the register, but other sources call the wood "Scratta".

- Will of Sir Thomas Hewett of Shireoakes, Nottinghamshire (P.C.C. 1726, Plymouth quire).

- Holland, History of Worksop, pp. 176-77 (Google).

- The Works of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Vol. V, pp. 227-28 (Google).

- Will of Dame Frances Hewett, Widow of Shire Oaks, Nottinghamshire (P.C.C. 1756, Glazier quire).

- A. Dugdale, 'John Hallam, a poor country joiner', Georgian Group Journal, VII (1997), pp. 37-42.

- P. Smith, 'Rufford Abbey and its gardens in the 17th and 18th centuries', English Heritage Historical Review, Vol. 4 (2009), pp. 122-53, at p. 142 (eastmidlandshistory.org.uk pdf).

- "St Andrew" was the maiden surname of John Hewett's Thornhaugh great-grandmother: see E.R. Edwards, 'Thornhaugh, John (1648-1723), of Fenton, Notts.', in B.D. Henning (ed.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1660-1690 (from Boydell and Brewer, 1983), History of Parliament Online.

- Will and probate of Sir Thomas Hewett of Shireoakes, Nottinghamshire (P.C.C. 1726, Plymouth quire).

- Lord Hawkesbury, 'Notes on Osberton, Scofton, Rayton, Bilby, Hodsock, Fleecethorp, &c.', Transactions of the Thoroton Society, V (1901), Supplement, pp. 9-31, at pp. 15-16 (Internet Archive).

- For the story, see Holland, History of Worksop, p. 177, note (Google). They had a descendant known as "Shireoaks Tom".

- Journals of the House of Lords, Beginning 26 George II, 1753, Vol. XXVIII, p. 550 (Google).

- J.A. Venn and J. Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses, Part 1 Vol. 4 (Cambridge University Press, 1927), p. 231 (Internet Archive).

- Milner, Records of the Lumleys, pp. 209-12 (Internet Archive).

- Portraits of Mr and Mrs Thornhaugh Hewett were in the Savile collection at Carlton Terrace in 1905, see Catalogue of Portraits, Miniatures &c.: in the possession of Cecil George Savile (Private, 4th Earl of Liverpool, 1905), p. 108, nos. 347, 348 (Internet Archive).

- R. White, Worksop, "The Dukery" and Sherwood Forest, pp. 178-79 (Internet Archive).

- C.G.S. Foljambe, 'The Nottinghamshire family of Thornhagh: from the original MS of 1683, and continued to the present time', The Reliquary, Quarterly Archaeological Journal and Review, XVIII (1876-1877), pp. 235-38 (Internet Archive).

- J. Brooke, 'Thornhagh, John (c.1721-87), of Osberton and Shireoaks, Notts. and South Kelsey, Lincs.', in L. Namier and J. Brooke (eds), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1754-1790, (from Boydell and Brewer, 1964), History of Parliament Online.

- Hawkesbury, 'Notes on Osberton, &c.', at pp. 15-16 (Internet Archive).

- 'Unregistered Park and Garden: Osberton Hall and Scofton Hall', Report for Bassetlaw District Council, NCC/BDC ref. 0041, at p. 4. (bassetlaw.gov.uk pdf).

- E. Eddison, History of Worksop; with Sketches of Sherwood Forest and the Neighbourhood (Longman and Co., London 1854), p. 224 (Internet Archive).

- W. White, History, Gazetteer and Directory of Nottinghamshire, and the Town and County of the Town of Nottingham (William White, Sheffield 1823), pp. 469-70 (Google).

- "Foljambe of Osberton: Deeds and Estate Papers", Correspondence of George Savile and John Hewett, Nottinghamshire Archives, ref. DD/FJ/11/1/1-7 (The National Archives (UK), Discovery Catalogue).

- 'A List of the Society of Antiquaries of London, May 2 1771', Gentleman's Magazine Vol. XLI (London 1771), p. 258 (Google).

- F. Grose and T. Astle (comp.), The Antiquarian Repertory: a Miscellaneous Assemblage of Topography, History, Biography, Customs and Manners, New Edition, 4 vols (Edward Jeffery, London 1808), III, pp. 314-16 (Google).

- Will of John Hewett of Shireoakes, Nottinghamshire (P.C.C. 1787, Major quire).

- Admiral John Norris was the last Mrs Hewett's grandfather: see N. Jeffares, 'John Norris Hewett, a singular woman', at Wordpress, (2016). ("https://neiljeffares.wordpress.com/2016/10/19/john-norris-hewett-a-singular-woman/").

- Will of John Norris Hewett, widow of Richmond, Surrey (P.C.C. 1790, Bishop quire).

- J. Throsby (ed.), Thoroton's History of Nottinghamshire. Republished with Large Additions (J. Throsby, Nottingham 1796), III, p. 299 (Google).

- Foster, Joseph (1888–1892). . Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715–1886. Oxford: Parker and Co – via Wikisource.

- J.A. Venn and J. Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses, Part 1 Vol. 2 (1922), p. 361 (Internet Archive).

- White, Directory, pp. 469-70 (Google).

- Holland, History of Worksop, pp. 177-78 (Internet Archive).

- R. White, Worksop, "The Dukery" and Sherwood Forest (1875), p. 85 (Internet Archive).

- Holland, History of Worksop; W. White, Directory, pp. 469-70.

- 'Cap. cxv: Shireoaks District Church Act, 1861', in G.K. Rickards, The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 25 Part 1: 24 and 25 Victoria, A.D. 1861 (Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1861), pp. 458-59 (Google).