Shimashki Dynasty

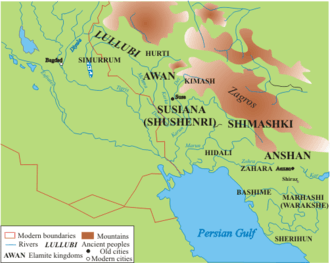

The Shimashki or Simashki dynasty (𒈗𒂊𒋛𒈦𒄀𒆠, lugal-ene si-mash-giki "Kings of the country of Simashgi"), was an early dynasty of the ancient region of Elam, to the southeast of Babylonia, in approximately 2200-1900 BCE.[1] A list of twelve kings of Shimashki is found in the Elamite king-list of Susa, which also contains a list of kings of Awan dynasty.[2] It is uncertain how historically accurate the list is (and whether it reflects a chronological order[3]), although some of its kings can be corroborated by their appearance in the records of neighboring peoples.[2] The Dynasty corresponds to the middle part of the Old Elamite period (dated c.2700 – c. 1600 BC). It was followed by the Sukkalmah Dynasty. Shimashki was likely near today's Isfahan.

Nature of the "Dynasty"

Daryaee suggests that, despite the impression from the king-list that the rulers of Shimashki was a dynasty of sequential rulers, it is perhaps better to think of Shimashki as an alliance of various peoples "rather than a unitary state."[4]

Occupation of Mesopotamia

The Shimashki confederacy led an alliance against the Ur III Empire, and managed to defeat its last ruler Ibbi-Sin.[5] After this victory, they destroyed the kingdom, looted the capital of Ur, and ruled through military occupation for the next 21 years.[5][6]

The Shimashki rulers became participants in an ongoing conflict with the rulers of Isin and Larsa after the fall of Third Dynasty of Ur.[7]

Under the Shimashki and their successors the Sukkalmah, Elam then became one of the most powerful kingdoms of West Asia, influencing the territories of Mesopotamia and Syria through commercial, military or diplomatic contacts.[5] Expansion in Mesopotamia was only halted by the Babylonian king Hammurabi in the 18th century BC.[5] After a prolonged conflict, the military forces of Elam were finally forced to retreat their forces positioned along the Tigris river, and to return to Susa.[5]

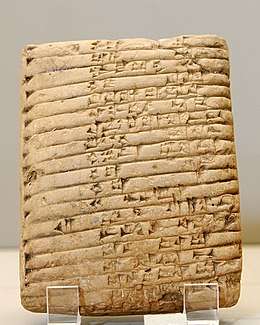

Paleography

Shimashki is first mentioned on the inscription to an image of Puzur-Inshushinak, king of Awan around 2100 BC, which depicts a Shimashkian king as subordinate to him.[8]

The Shimashki dynasty was followed by the Sukkalmah dynasty (c. 1900-1500).[7]

Individual Rulers

The names in the king-list, as found in Potts, are "Girnamme, Tazitta, Ebarti, Tazitta, Lu[?]-[x-x-x]-lu-uh-ha-an, Kindattu, Idaddu, Tan-Ruhurater, Ebarti, Idaddu, Idaddu-napir, Idaddu-temti, twelve Sumerian kings" (bracketed letters original).[9]

Girnamme ruled at the same time as Shu-Sin, king of Ur, and was involved, as either a groom or simply a facilitator, in the marriage of Shu-Sin's daughter.[10] Gwendolyn Leick places this event in 2037 BCE.[10] Girnamme, along with Tazitta and Ebarti I, appears in "Mesopotamian texts establishing food rations issued to messengers," texts from 2044-2032 BCE.[8]

Tazitta, the second figure in the list, is referred to in a document from the eighth year of the reign of Amar-Sin of Ur.[3]

Kindattu was also known as Kindadu.[11] A Kindattu, who according to Daryaeee was "apparently" the Shimashkian king of the list above, lead the army that destroyed the Third Dynasty of Ur in 2004 BCE.[3] The operation was a joint effort between Kindattu and his then-ally Ishbi-Erra, who defeated Ur and captured Ibbi-Sin, its king.[8] The Ishbi-Erra hymn claims that Ishbi-Erra later expelled Kindattu from Mesopotamia.[3]

Idaddu I (also known as Indattu-Inshushinak,[8] or simply Indattu) called himself "king of Shimashki and Elam".[8] According to Stolper and André-Salvini, he was the son of Kindattu,[8] while Gwendolyn Leick calls him "son of Pepi," claiming that Kindattu may have been his grandfather.[12] According to Leick he ascended to the throne of Shimashki around 1970 BCE.[12]

Tan-Ruhurater, also known as Tan-Ruhuratir, formed an alliance with Bilalama, the governor of Eshnunna, by marrying Bilama's daughter Mê-Kubi.[13][14]

Ebarti II of Shimashki may have been the same individual known as Ebarat, a Sukkalmah, or "Grand Regent".[15] If so, he was ruler simultaneously to the next member of the list of twelve Shimaskin kings: Idaddu II.[15]

Idaddu II was the son of Tan-Ruhurater, during whose reign he oversaw building projects as the governor of Susa.[16] According to Leick, he was the last of the Shimashkian kings.[1]

Rulers

| Name | Portrait | Title | Born-Died | Entered office | Left office | Family Relations | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shimashki Dynasty,[17][18] c. 2100–c. 1928 BC | ||||||||

| 1 | The unnamed king of Simashki | king of Simashki | ?–c. 2100 BC | ? | c. 2100 BC | ? | cont. Kutik-Inshushinak king of Awan | |

| 2 | Gir-Namme I | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | ||

| 3 | Tazitta I | king of Simashki | ?–? | c. 2040 BC[19] | c. 2037 BC[19] | ? | ||

| 4 | Eparti I | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | c. 2033 BC[19] | ? | ||

| 5 | Gir-Namme II | king of Simashki | ?–? | c. 2033 BC | ? | |||

| 6 | Tazitta II | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | ? | |||

| 7 | Lurak-Luhhan | king of Simashki | ?–2022 BC | c. 2028 BC | 2022 BC | ? | ||

| 8 | Hutran-Temti | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | ||

| 9 | Indattu-Inshushinak I | king of Simashki | ?–2016 BC | ? | 2016 BC | son of Hutran-Temti | ||

| 10 | Kindattu | king of Simashki | ?–? | before 2006 BC | after 2005 BC | son of Tan-Ruhuratir | conqueror of Ur | |

| 11 | Indattu-Inshushinak II |  Idadu II, seated, offering an ax, symbol of dignity, to Kuk Simut |

king of Simashki | ?–? | c. 1980 BC | ? | son of Pepi[20] | cont. Shu-Ilishu king of Isin & Bilalama king of Eshnunna |

| 12 | Tan-Ruhuratir I | king of Simashki | ?–? | c. 1965 BC | ? | son of Indattu-Inshushinnak II | cont. Iddin-Dagan king of Isin | |

| 13 | Indattu-Inshushinak III | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | ? | son of Tan-Ruhuratir I | more than 3 years | |

| 14 | Indattu-Napir | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | ? | ? | ||

| 15 | Indattu-Temti | king of Simashki | ?–? | ? | 1928? BC | ? | ||

See also

References

- Gwendolyn Leick (31 January 2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-134-78795-1.

- I. E. S. Edwards; C. J. Gadd; N. G. L. Hammond (31 October 1971). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 654. ISBN 978-0-521-07791-0.

- Touraj Daryaee (16 February 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-19-020882-0.

- Touraj Daryaee (16 February 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-19-020882-0.

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. Routledge. p. 221. ISBN 9781134159079.

- D. T. Potts (12 November 2015). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-107-09469-7.

- Sigfried J. de Laet; Ahmad Hasan Dani (1994). History of Humanity: From the third millennium to the seventh century B.C. UNESCO. p. 579. ISBN 978-92-3-102811-3.

- Matthew Stolper; Béatrice André-Salvini (1992). "The Written Record". The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-87099-651-1.

- D. T. Potts (1999). The Archaeology of Elam. Cambridge University Press. p. 141.

- Gwendolyn Leick (31 January 2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-134-78795-1.

- Touraj Daryaee (16 February 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-19-973215-9.

- Gwendolyn Leick (31 January 2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-134-78795-1.

- On the alliance, see Katrien De Graef; Jan Tavernier (7 December 2012). Susa and Elam. Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives.: Proceedings of the International Congress held at Ghent University, December 14-17, 2009. BRILL. p. 54. ISBN 978-90-04-20741-7.

- On Bilalama's position as governor of Eshnunna, see Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). University of Toronto Press. p. 491. ISBN 978-0-8020-5873-7.

- Elizabeth Carter; Matthew W. Stolper (1984). Elam: Surveys of Political History and Archaeology. University of California Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-520-09950-0.

- Gwendolyn Leick (31 January 2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-134-78796-8.

- Some archaeologists have suggested that Simashki was located in the north of Elam and Anshan near modern Isfahan.

- Cameron, 1936; The Cambridge History of Iran; Hinz, 1972; The Cambridge Ancient History; Majidzadeh, 1991; Majidzadeh, 1997; Vallat "Elam ...", 1998.

- Potts, 1999.

- Hinz, 1972.

Sources

- Hinz, W., "The Lost World of Elam", London, 1972 (tr. F. Firuznia, دنیای گمشده ایلام, Tehran, 1992)

- Potts, D. T., The Archaeology of Elam, Cambridge University Press, 1999.