Shieling

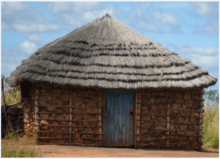

A shieling (Scottish Gaelic: àirigh), also spelt sheiling,[1] shealing and sheeling,[2] is a hut, or collection of huts, once common in wild or lonely places in the hills and mountains of Scotland and northern England. The word is also used for a mountain pasture for the grazing of cattle in summer, implying transhumance between there and a valley settlement in winter.

Etymology

The term shieling is mainly Scottish, originally denoting a summer dwelling on a seasonal pasture high in the hills,[3] particularly for shepherds and later coming to mean a more substantial and permanent small farm building in stone. The first recorded use of the term is from 1568.[4] The term is from shiel, from the Northern dialect Middle English forms schele or shale, probably akin to Old Frisian skul meaning 'hiding place' and to Old Norse Skjol meaning 'shelter' and Skali meaning 'hut'.[5]

Seasonal dwelling

Farmers and their families lived in shielings during the summer to have their livestock graze common land. Shielings were therefore associated with the transhumance system of agriculture. The mountain huts generally fell out of use by the end of the 17th century, although in remote areas this system continued into the 18th.[6]

Ruins of shielings are abundant in high or marginal land in Scotland and Northern England, along with place-names containing "shield" or their Gaelic equivalents, with names such as Pollokshields in Glasgow,[7] Arinagour on the island of Coll,[8] Galashiels in the Scottish Borders,[9][10] and "Shiels Brae" near Bewcastle.[11] Some were constructed of turf and tend to gradually erode and disappear but traces of stone-built structures persist. Some shielings are mediaeval in origin and were occasionally occupied permanently after abandonment of the transhumance system. The construction of associated structures such as stack-stands and enclosures indicate that in these cases they became farmsteads, some of which evolved into modern farms.[11]

In his 1899 book The Lost Pibroch, Neil Munro refers to the shieling as something temporary: "the women, posting blankets for the coming shieling...";[12] "It was about the time Antrim... came scouring through our glens..., with not a shieling from end to end, except on the slopes of Shira Glen...";[13] "...for never a shieling passed but the brosey folks came pouring down Glenstrae, scythe, sword, and spear, and went back with the cattle before them..."[14]

Memories in folksong, literature and poetry

The well-known folksong Mairi's Wedding contains the phrase "past the shieling, through the town" which helps protect this word from obscurity. A Gaelic song (covered on Uam by Julie Fowlis) is Bothan Àirigh am Bràigh Raithneach ("A shieling on the Braes of Rannoch"),[15] while the 'weaver poet' Robert Tannahill's song to "Gilly Callum" begins "I'll hie me to the shieling hill, / And bide amang the braes, Callum..."[16]

Insofar as a shiel is a simple enclosure like a shell and shieling may describe action, the 1820 novel The Monastery, by Sir Walter Scott notes that in Scotland, a "shieling-hill" was a place for separating wheat corn from chaff by hand. Here shieling is a verb describing the act of removing wheat grain shells, combined with the noun hill.[17][18][19] Further use of shiel in this order is found in Sir Walter Scott's The Black Dwarf (novel), in which in 1816 was written "...[W]e took their swords and pistols as easily as ye wad shiel peacods."[20]

The temporary nature of the shieling, and its location high in the Scottish hills, are alluded to in the musicologist William Sharp's Shieling Song of 1896, which he published under the pseudonym "Fiona MacLeod": "I go where the sheep go, with the sheep are my feet... / O lover, who loves me, / Art thou half so fleet? / Where the sheep climb, the kye go, / There shall we meet!" (Kye means "cattle".)[21]

The shieling could be on a Scottish island, as in Marjory Kennedy-Fraser's delicate tune "An island shieling", recorded on "Songs of the Hebrides" by Florence McBride.[22][23] Edward Thomas's poem "The Shieling" evokes the loneliness of a quiet old highland building that "stands alone/Up in a land of stone...A land of rocks and trees..."[24]

Shiel is found in a 1792 Robert Burns song, Bessy and her Spinnin' Wheel: "On lofty aiks the cushats wail, / And Echo cons the doolfu' tale; / The lintwhites in the hazel braes, / Delighted, rival ither's lays; / The craik amang the claver hay, / The pairtrick whirring o'er the ley, / The swallow jinkin' round my shiel, / Amuse me at my spinnin' wheel."[25] Shiel is found again in a 1792 Robert Burns poem, The Country Lass.[26] There it mentions a shiel used for dairy production as referenced in the following section.

Surviving shielings in Scotland and elsewhere

Among the many surviving buildings named shieling is Shieling Cottage, Rait, Perth and Kinross, an 18th-century cottage of clay-bonded rubble, originally roofed in thatch, now in slate.[27][lower-alpha 1]

The 'Lone Shieling', built in 1942 in Canada's Cape Breton Highlands National Park, is modelled on a Scottish 'bothran' or shepherds' hut of the type that was used during the summer when it was possible to move the sheep up on to the hills to graze. It has the same design as the Lone Sheiling on the Scottish isle of Skye,[28] romanticised in the lines "From the lone shieling of the misty island/Mountains divide us and the waste of seas – Yet still the blood is strong, the heart is Highland, And we in dreams behold the Hebrides."[3]

Derek Cooper, in his 1983 book on Skye, suggests that the isolation of shielings gave opportunity for "sexual experiment[ation]", and in evidence identifies a moor named "Àirigh na suiridh", the bothy of lovemaking.[3] The song Bothan Àirigh am Bràigh Raithneach confirms this with the verse "And we'll rear them in a shieling on the Braes of Rannoch, in the brush-wood enclosed hut of dalliance."[15]

The buildings on the moors were repaired each summer when the people arrived with their cattle; they made butter and cheese, and "gruthim", salted buttered curds.[3]

See also

Notes

- However, the cottage may be named for the nearby horseshoe-shaped farmstead.

References

- "sheiling". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary: Sheeling". Encyclo.co.uk. 1913. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Cooper, 1983. pp. 124–125

- "Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". shieling. Merriam-Webster. 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- "shiel". Webster's Third New International Dictionary. 3 (3 ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 1986. p. 2094.

- As discussed in "Britain and Ireland 1050–1530: Economy and Society", By R. H. Britnell, pg 209.

- "Scottish National Dictionary 1700-". Dictionary of the Scots Language. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Learn Gaelic". Learn Gaelic.Scot/Dictionary. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Scots Words and Place-names". Place-Name Glossary. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- "Galashiels". Scottish Places. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- "Introductions to Heritage Assets: Shielings". English Heritage / Historic England. May 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- Munro, 1899. p. 35

- Munro, 1899. p. 52

- Munro, 1899. p. 134

- "Na h-òrain air 'Uam' / The songs on 'Uam'". Julie Fowlis. 2011. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- "I'll Hie Me to the Shieling Hill". Glasgow Guide. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- "The Monastery". Archibald Constable, and John Ballantyne (Edinburgh); Longman, Hurst Rees, Orme, and Brown (London). Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Schele v." Dictionary of the Scots Language. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Sheel v." Dictionary of the Scots Language. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "The Black Dwarf". William Blackwood, Edinburgh; John Murray, London. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- Sharp, William (1896). "Vocal settings of "Shieling song"". The LiederNet Archive. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Songs of the Hebrides, Part 1: Birlinn of Clanranald / An island shieling / Cockle gatherer". DB 591 (WA 10954). Columbia. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Discography section 14: Ma-McKay" (PDF). National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Thomas, Edward (1878–1917). "The First World War Poetry Digital Archive: The Shieling". OUCS.ox.ac.uk (originally Faber & Faber). Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Bessy and her Spinnin' Wheel". Robert Burns. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "The Country Lass". Robert Burns. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- Canmore database (11 September 2012). "Canmore: Rait, The Shieling". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Lone Sheiling". Canada's Historic Places. 2 June 1994. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

Bibliography

- Cooper, Derek (1983). Skye. Routledge. pp. 124–125. ISBN 9780710095657.

- Munro, Neil (1899). "The Lost Pibroch and other Shieling Stories". William Blackwood and Sons.