Shapira Scroll

The Shapira Scroll (also known as the Shapira Strips) was a manuscript carrying Biblical verses written in Paleo-Hebrew script. It was presented by Moses Shapira in 1883 as an ancient Biblical artifact, and was the focus of a major archaeological controversy.

.jpg)

The scroll consisted of fifteen leather strips, and Shapira claimed to have found it in Wadi Mujib near the Dead Sea. The Hebrew text hinted at a different version of Deuteronomy, including an eleventh commandment: "Thou shalt not hate thy brother in thy heart: I am God, thy God". The authenticity of the scroll was quickly questioned by scholars, and the shame brought about by the accusation of forgery drove Shapira to suicide in 1884.

The scroll disappeared and then reappeared a couple of years later in a Sotheby's auction, where it was sold for £25. It was considered to have been destroyed in an 1899 fire at the house of the presumed final owner, Sir Charles Nicholson. In 2011 Australian researcher Matthew Hamilton identified its purchaser as Dr. Philip Brookes Mason. Mason's wife sold her husband's possessions after his death in 1903. The whereabouts of the scroll are unknown.

Presentation of the scroll

Shapira's description of the discovery of the scroll is contained within a handwritten letter from Shapira to Professor Hermann Strack of Berlin on 9 May 1883:[1]

I am going to surprise you with a notice and a short description of a curious manuscript written in old Hebrew or Phoenician letters upon small strips of embalmed leather and seems [sic] to be a short unorthodoxical [sic] book of the last speech of Moses in the plain of Moab ... In July 1878 I met several Bedouins in the house of the well-known Sheque Mahmud el Arakat, we came of course to speak of old inscriptions. One Bedouin asserted that the antique brings blessedness to the place where it lays. And begins to tell a history to about [sic] the following effect. Several years ago some Arabs had occasion to flee from their enemies & hid themselves in caves high up in a rock facing the Moujib (the neues Arnon [sic]) they discovered there several bundles of very old rugs. Thinking they may [sic] contain gold they peeled away a good deal of Cotton or Linen & found only some black charms & threw them away; but one of them took them up & and [sic] since having the charms in his tent, he became a wealthy man having sheeps [sic] etc.

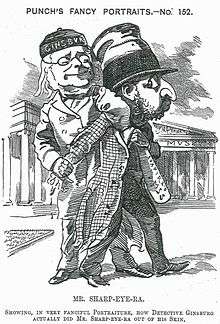

Shapira sought to sell the scroll to the British Museum for a million pounds, and allowed the Museum to exhibit two of the 15 strips.[2] The exhibition was attended by thousands. Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau, whom Shapira had previously denied access to the scroll, was among the attendees and, after close examination of the two strips on display, declared them to be forgeries.[3] Soon afterward British biblical scholar Christian David Ginsburg came to the same conclusion. Later, Clermont-Ganneau suggested that the leather of the Deuteronomy scroll might have been cut from the margin of a genuine Yemenite scroll that Shapira had previously sold to the Museum.[3]

Yours truly, Moses Wilhelm Shapira"

Shapira's letter to Ginsburg, August 23, 1883[4]

Aftermath

Shapira fled London in despair, his name ruined and all of his hopes crushed. Six months later, on 9 March 1884, he shot himself at the Hotel Willemsbrug in Rotterdam.[5]

The British Museum put up the scroll for auction at Sotheby's in 1885 and it was purchased by Bernard Quaritch, a bookseller. Two years later, Quaritch listed the scroll for sale for £25. The scroll was thought to have been purchased by Sir Charles Nicholson, and destroyed in a fire in Nicholson's study in England in 1899.[3][6] In 2011 Australian researcher Matthew Hamilton identified its purchaser as Dr. Philip Brookes Mason;[7] the identification was publicized in a 2014 documentary by Yoram Sabo, Shapira and I,[8] and a 2016 book by Professor Chanan Tigay, The Lost Book of Moses.[9][7][10]

Re-assessment in light of the Dead Sea Scrolls

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947, in approximately the same area Shapira claimed his scroll was discovered, cast some doubt on the initial charges of forgery.[11][12]

Despite the assessment of contemporary scholars—including not just Clermont-Ganneau and Ginsburg, but also German ones from Halle, Leipzig and Berlin—which rested on doubts about the antiquity of the leather or purported flaws in the Hebrew, and even leaving aside the fact that the peculiar "eleventh commandment" showed Christian leanings which could be connected to Shapira's own conversion, there have always been researchers claiming to have reasons to believe that the Shapira scroll might be a genuine ancient artifact after all.[13]

Professor Menahem Mansoor, chairman of the Department of Hebrew and Semitic Studies at the University of Wisconsin, announced in 1956 that the scroll may have been authentic.[14] In a book published in 1958 Mansoor concluded that “neither the internal nor the external evidence... supports the idea of a forgery... there is justification... for a re-examination of the case”.[15] Mansoor’s conclusion was supported by Jacob L. Teicher and attacked by Moshe H. Goshen-Gottstein and by Oskar K. Rabinowicz.[16]

References

- Guil 2017, p. 9.

- Reiner 1995, pp. 109, 115, 116.

- Press, Michael (11 September 2014). "'The Lying Pen of the Scribes': A Nineteenth-Century Dead Sea Scroll". The Appendix. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- Reiner 1995, p. 110.

- Newspaper "Het Vaderland", March 12, 1884.

- Crown 1970, pp. 421–423.

- Tigay, Chanan. "Was this the first Dead Sea Scroll?".

- Shapira & I

- Guil 2017, p. 25: "Surprisingly, contrary to the belief held for the last forty five years, the Shapira scroll was not destroyed in a fire that erupted in the house of Sir Charles Nicholson, near London. We presently know that it was Dr. Philip Brookes Mason of Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire, who acquired the Shapira scroll in 1888 or beginning of 1889 and probably held it until his death in 1903. There are indications that, after his death, his wife sold his life's collection at an auction. Some good detective work might lead to the rediscovery of the Shapira scroll."

- OBITUARY NOTICE OF PHILIP BROOKES MASON, by The Rev. CHAS. F. THORNEWILL; Read before the Society, September 14, 1904, Journal of Conchology, VOL XI, 1904 — 1906, p.105 "It is not generally known that Mr. Mason became the eventual possessor of the notorious 'Shapira' manuscript, which for a time deceived some of the most experienced authorities on such matters, but was at length discovered to be a remarkably clever forgery."

- Allegro 1965.

- Vermès 2010.

- Guil 2017, pp. 6–27.

- "Dead Sea Scroll Traced to Jew Who Committed Suicide 70 Years Ago - Jewish Telegraphic Agency". www.jta.org. 14 August 1956.

- Mansoor 1958, p. 225.

- Reiner 1997, p. Endnote 2.

Further reading

Original scholarly papers

- Clermont-Ganneau, Les fraudes archéologiques en Palestine, Paris, 1885, pp. 107ff., 152ff. 159, 173

- Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement (October 1883), pp. 195–209;

- Hermann Guthe, Fragmente einer Lederhandschrift (Leipzig, 1883)

- A.C.R. Carter, “Shapira, the Bible Forger,” in Let Me Tell You (London, 1940), pp. 216–219

- Walter Besant, Autobiography of Sir Walter Besant (New York, 1902; reprint, St. Clair Shores, MI: Scholarly Press, 1971), pp. 161–167.

- Yaakov Asya, “Parashat Shapira,” supplement to: Myriam Harry [pseud.], Bat Yerushalayim Hakatanah (in Hebrew) (A. Levenson Publishing House, 1975) originally published as La Petite Fille de Jerusalem (Paris, 1914).

Initial reappraisal

- Mansoor, Menahem (1958). "The Case of Shapira's Dead Sea (Deuteronomy) Scrolls of 1883" (PDF). Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters. 47: 183–229.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- J.L. Teicher (“The Genuineness of the Shapira Manuscripts,” Times Literary Supplement, 22 March 1957).

- Moshe H. Goshen-Gottstein “The Shapira Forgery and the Qumran Scrolls,” Journal of Jewish Studies 7 [1956], 187–193, and “The Qumran Scrolls and the Shapira Forgery” [in Hebrew], Ha’aretz, 28 December 1956

- Oskar K. Rabinowicz, The Shapira Forgery Mystery,” Jewish Quarterly Review, n.s. 47 [1956–1957], pp. 170–183)

Modern scholarship

- Allegro, John Marco (1965). The Shapira affair. Doubleday. OCLC 543413.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Judith Anne (2005). John Marco Allegro: The Maverick of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-0-8028-2849-1.

- Crown, Alan D. (1970). "The Fate of the Shapira Scroll". Revue de Qumran. 7 (27): 421–423.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davila, James R. (3 November 2013). "The Shapira forgeries raise their moldering heads again". Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- Vermès, Géza (2010). The story of the scrolls: the miraculous discovery and true significance of the Dead Sea scrolls. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-104615-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guil, Shlomo (2017). "The Shapira Scroll was an Authentic Dead Sea Scroll". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 149 (1): 6–27. doi:10.1080/00310328.2016.1185895.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Press, Michael (July 1214). ""The Lying Pen of the Scribes": A Nineteenth-Century Dead Sea Scroll". The Appendix. 2 (3). Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- Rabinowicz, Oskar K. (July 1965). "The Shapira Scroll: An nineteenth-century forgery". The Jewish Quarterly Review: New Series. 56 (1): 1–21. JSTOR 1453329.

- Reiner, Fred N. (1995). "C.D. Ginsburg and the Shapira affair: a nineteenth-century Dead Sea Scroll controversy" (PDF). British Library Journal. 21 (1): 109–127.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reiner, Fred N. (28 June 2011). Standing at Sinai: Sermons and Writings. AuthorHouse. pp. 301–. ISBN 978-1-4567-6507-1.

- Reiner, Fred (1997). "Tracking the Shapira Case: A Biblical Scandal Revisited". Biblical Archaeology Review.

Also list of sources at

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Tigay, Chanan (2017). The Lost Book of Moses: The Hunt for the World's Oldest Bible. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-220642-8.

- Neil Asher Silberman, “One Million Pounds Sterling, the Rise and Fall of Moses Wilhelm Shapira, 1883–1885,” in Digging for God and Country (New York: Knopf, 1982);

- Mansoor, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Textbook and Study Guide, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1983), chap. 25, pp. 215–224;

- Colette Sirat, “Les Fragments Shapira,” Revue des études juives 143 (1984), pp. 95–111;

- Hendrik Budde, “Die Affaere um die ‘Moabitischen Althertuemer,’” in Budde and Mordechay Lewy, Von Halle Nach Jerusalem (Halle: Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt, 1994), pp. 106–117.

- Guil,Shlomo In Search of the Shop of Moses Wilhelm Shapira, the Leading Figure of the 19TH Century Archaeological Enigma

Primary sources

- British Library Add. MS. 41294, “Papers Relative to M. W. Shapira’s Forged MS. of Deuteronomy (A.D. 1883–1884).”