Shanks transformation

In numerical analysis, the Shanks transformation is a non-linear series acceleration method to increase the rate of convergence of a sequence. This method is named after Daniel Shanks, who rediscovered this sequence transformation in 1955. It was first derived and published by R. Schmidt in 1941.[1]

This viewpoint has been persuasively set forth in a delightful paper by Shanks (1955), who displays a number of amazing examples, including several from fluid mechanics.

Milton D. Van Dyke (1975) Perturbation methods in fluid mechanics, p. 202.

Formulation

For a sequence the series

is to be determined. First, the partial sum is defined as:

and forms a new sequence . Provided the series converges, will also approach the limit as The Shanks transformation of the sequence is the new sequence defined by[2][3]

where this sequence often converges more rapidly than the sequence Further speed-up may be obtained by repeated use of the Shanks transformation, by computing etc.

Note that the non-linear transformation as used in the Shanks transformation is essentially the same as used in Aitken's delta-squared process so that as with Aitken's method, the right-most expression in 's definition (i.e. ) is more numerically stable than the expression to its left (i.e. ). Both Aitken's method and the Shanks transformation operate on a sequence, but the sequence the Shanks transformation operates on is usually thought of as being a sequence of partial sums, although any sequence may be viewed as a sequence of partial sums.

Example

As an example, consider the slowly convergent series[3]

which has the exact sum π ≈ 3.14159265. The partial sum has only one digit accuracy, while six-figure accuracy requires summing about 400,000 terms.

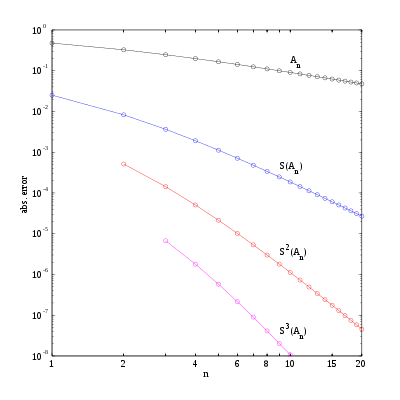

In the table below, the partial sums , the Shanks transformation on them, as well as the repeated Shanks transformations and are given for up to 12. The figure to the right shows the absolute error for the partial sums and Shanks transformation results, clearly showing the improved accuracy and convergence rate.

| 0 | 4.00000000 | — | — | — |

| 1 | 2.66666667 | 3.16666667 | — | — |

| 2 | 3.46666667 | 3.13333333 | 3.14210526 | — |

| 3 | 2.89523810 | 3.14523810 | 3.14145022 | 3.14159936 |

| 4 | 3.33968254 | 3.13968254 | 3.14164332 | 3.14159086 |

| 5 | 2.97604618 | 3.14271284 | 3.14157129 | 3.14159323 |

| 6 | 3.28373848 | 3.14088134 | 3.14160284 | 3.14159244 |

| 7 | 3.01707182 | 3.14207182 | 3.14158732 | 3.14159274 |

| 8 | 3.25236593 | 3.14125482 | 3.14159566 | 3.14159261 |

| 9 | 3.04183962 | 3.14183962 | 3.14159086 | 3.14159267 |

| 10 | 3.23231581 | 3.14140672 | 3.14159377 | 3.14159264 |

| 11 | 3.05840277 | 3.14173610 | 3.14159192 | 3.14159266 |

| 12 | 3.21840277 | 3.14147969 | 3.14159314 | 3.14159265 |

The Shanks transformation already has two-digit accuracy, while the original partial sums only establish the same accuracy at Remarkably, has six digits accuracy, obtained from repeated Shank transformations applied to the first seven terms As said before, only obtains 6-digit accuracy after about summing 400,000 terms.

Motivation

The Shanks transformation is motivated by the observation that — for larger — the partial sum quite often behaves approximately as[2]

with so that the sequence converges transiently to the series result for So for and the respective partial sums are:

These three equations contain three unknowns: and Solving for gives[2]

In the (exceptional) case that the denominator is equal to zero: then for all

Generalized Shanks transformation

The generalized kth-order Shanks transformation is given as the ratio of the determinants:[4]

with It is the solution of a model for the convergence behaviour of the partial sums with distinct transients:

This model for the convergence behaviour contains unknowns. By evaluating the above equation at the elements and solving for the above expression for the kth-order Shanks transformation is obtained. The first-order generalized Shanks transformation is equal to the ordinary Shanks transformation:

The generalized Shanks transformation is closely related to Padé approximants and Padé tables.[4]

See also

Notes

- Weniger (2003).

- Bender & Orszag (1999), pp. 368–375.

- Van Dyke (1975), pp. 202–205.

- Bender & Orszag (1999), pp. 389–392.

References

- Shanks, D. (1955), "Non-linear transformation of divergent and slowly convergent sequences", Journal of Mathematics and Physics, 34: 1–42, doi:10.1002/sapm19553411

- Schmidt, R. (1941), "On the numerical solution of linear simultaneous equations by an iterative method", Philosophical Magazine, 32: 369–383

- Van Dyke, M.D. (1975), Perturbation methods in fluid mechanics (annotated ed.), Parabolic Press, ISBN 0-915760-01-0

- Bender, C.M.; Orszag, S.A. (1999), Advanced mathematical methods for scientists and engineers, Springer, ISBN 0-387-98931-5

- Weniger, E.J. (1989). "Nonlinear sequence transformations for the acceleration of convergence and the summation of divergent series". Computer Physics Reports. 10 (5–6): 189–371. arXiv:math.NA/0306302. Bibcode:1989CoPhR..10..189W. doi:10.1016/0167-7977(89)90011-7.