Rikka

Rikka (立花, "standing flowers") is a form of ikebana.[1]

History

The origins go back to Buddhist offerings of flowers, which are placed upright in vases. This tatehana (立て花) style was established in the Muromachi period (1333–1568).

The term came to be a popular synonym for ikebana in the 15th century, when rikka became a distinctive element of interior decoration in the reception rooms at the residences of the military leaders, nobility, and priests of the time.[2] It enjoyed a revival in the 17th century, and was used as a decorative technique for ceremonial and festive occasions.

One of the rikka proponents was Senkei Ikenobō (池坊専慶). The essence of the direction of the rite was clarified by Sen'ō Ikenobō (池坊専伝, 1482–1543) in the manuscript "Ikenobō Sen'ō kuden" (池坊専応口伝). Today it is still practice by the Ikenobō school of flower arranging.

Rikka later deveoped into a less formal style. It was eventually supplanted by the shōka style, which had a classical appearance but was asymmetrical in structure.[1]

The Saga Go-ryū (嵯峨御流) school has Buddhist roots and the style of floral offerings at the altar follows similar rules and is called shōgonka (荘厳華).[3][4]

Characteristics

The rikka style reflects the magnificence of nature and its display. For example, pine branches symbolize endurance and eternity, and yellow chrysanthemums symbolizes life. Trees can symbolise mountains, while grasses and flowers can suggest water. Until 1700, the arrangement consisted of seven main lines, and roughly starting in 1800, it consisted of nine main lines, each of which supports other minor lines. Important rules have been created that relate to the nature of the lines, their lengths and combinations of materials, the use of kenzan or komiwara (straw bundles), etc. Editing in that style can only be done through regular and long-term practice. The main axis, often the branch, is predominantly perpendicular, often the axis is formed by pine branches and is the most distinctive element of the arrangement. Both other lines are arranged at the bottom. The editing centre is filled like a bouquet of flowers.

Rikka style arrangements were also used for festive events and exhibitions. They are usually quite large from 1.5–4.5 metres and their construction requires the highest technical and artistic skills.[1]

Rikka shōfūtai (立花正風体) builds on the basics of traditional aesthetics of rikka direction. It is used by seven or nine lines when creating a pattern. The arrangement is to be varied and expresses the diversity of nature, which is very characteristic for this direction.

Rikka shimpūtai (立花新風体) was introduced in 1999. The characteristics lies in the arrangement of lines that create nine to eleven branches or stems and the essence lies above all in balance, harmony, perspective and movement, although it follows the rikka style. It is not important to follow the rule of only three plant materials. Exotic plant material is used as well as classical plants (saliva, pine).

Gallery

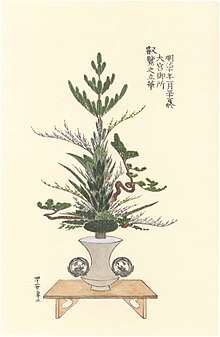

Rikka arrangement by Shūgyoku (from Rikka-zu narabini Sunamono-zu)

Rikka arrangement by Shūgyoku (from Rikka-zu narabini Sunamono-zu) Rikka arrangement by Daijuin (from Daijuin Rikka Sunamono-zu)

Rikka arrangement by Daijuin (from Daijuin Rikka Sunamono-zu) Sunamono arrangement

Sunamono arrangement

See also

References

- "Rikka - floral arrangement". Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Genshoku Chado Daijiten, ed. Iguchi Kaisen et. al. (Kyoto: Tankosha Publishing Co., 10th printing, 1975) (in Japanese). ISBN 4-473-00089-3 Entry for Kadō.

- https://helsinkisagaikebana.org/about-arrangement-styles/

- http://www.ikebana-bundesverband.de/files/index.php?menu=en&page=saga.html

External links

![]()