Sextus Tarquinius

Sextus Tarquinius was the third and youngest son of the last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, according to Livy, but by Dionysius of Halicarnassus he was the oldest of the three.[1]. It is possible he was the youngest of the family as the name “Sextus” translates to sixth in English implying he was the sixth of two living and three stillborn brothers. According to Roman tradition, his rape of Lucretia was the precipitating event in the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the Roman Republic.

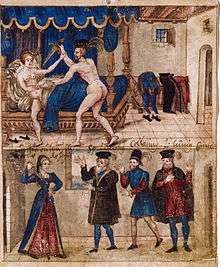

Rape of Lucretia

Tarquinius Superbus was besieging Ardea, a city of the Rutulians. The place could not be taken by force, and the Roman army lay encamped beneath the walls. While the king's sons, and their cousin, Tarquinius Collatinus, the son of Egerius, were feasting together, a dispute arose about the virtue of their wives. As nothing was happening in the field, they mounted their horses to pay a surprise visit to their homes. They first went to Rome, where they caught the king's daughters unaware at a splendid banquet. They then hastened to Collatia, and there, though it was late in the night, they found Lucretia, the wife of Collatinus, spinning amid her handmaids.

The beauty and virtue of Lucretia had fired the evil passions of Sextus Tarquinius. A few days later he returned to Collatia, where he was hospitably received by Lucretia as her husband's kinsman. In the dead of night he stealthily entered her chamber with a drawn sword. He forced her to yield to his sexual advances by telling her the alternative was that he would kill her and one of her slaves, place their bodies together, and claim he had defended her husband’s honour when he caught her having adulterous sex.

Soon after, Lucretia sent a message to both her husband and her father, Spurius Lucretius Tricipitinus, telling them everything. She then killed herself. The revolt that followed, led by her husband's friend and cousin, Lucius Junius Brutus, brought to an end the kingship of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus and brought about the beginning of the Roman Republic, Brutus becoming the first consul together with Collatinus. Sextus Tarquinius fled to Gabii, seeking to make himself king, but he was killed in revenge for his past actions.[2]

Cultural references

Art

Lucretia and Tarquin have been the subject of many paintings, including those by great artists.

Examples include:

- Tarquin and Lucretia by Titian, 1571

- Lucretia - Rembrandt (1664) [3]

- Tarquin and Lucretia - Tintoretto (c.1578) [4]

- Death of Lucretia - Ithell Colquhoun (1931) [5]

Literature

The story of Lucretia's rape is the subject of William Shakespeare's narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece, a work as long as many full-length plays, taking about two hours to recite. It has sometimes been performed as readers' theatre. Shakespeare alludes to Tarquin in his plays as well. In Cymbeline (Act 2, Scene 2), Iachimo has slipped into the sleeping Imogen's bedchamber, and compares himself to Tarquin:

... Our Tarquin thus

Did softly press the rushes, ere he waken'd

The chastity he wounded … .

In a soliloquy (known as the 'Dagger Soliloquy') from Macbeth, Macbeth alludes to Tarquin as a 'trope of stealth':

With Tarquin's ravishing strides, towards his design

Moves like a ghost. (Act 2 Scene 1, Lines 5-6)

In Shakespeare's history play Julius Caesar (Act 2, Scene 1), the character Brutus reflects on his ancestor's role in overthrowing Tarquin's father and the monarchy:

… Shall Rome stand under one man's awe?

What, Rome? My ancestors did from the streets of Rome the Tarquin drive, when he was call'd a king.

Tarquin, under his first name Sextus, is present with the Etruscan army in Thomas Babington Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome, when Lars Porsena, King of Clusium, attempts to restore the Tarquin dynasty to the Roman throne:

By the right wheel rode Mamilius, prince of the Latian name,

And by the left false Sextus, who wrought the deed of shame.

But when the face of Sextus was seen among the foes,

A yell that rent the firmament from all the town arose.

On the house-tops was no woman but spat toward him and hissed,No child but screamed out curses, and shook its little fist.[6]

Lucretia's rape is also the subject of Benjamin Britten's 1946 opera The Rape of Lucretia.

References

Citations

- Roman Antiquities Book 4.69

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1.60

- NGA

- image

- image

- Macaulay's Horatius at the Bridge

Sources

- Livy Ab urbe condita (From the Founding of the City) 1.53, 58

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sextus Tarquinius. |