Seven Dials Jazz Club

The Seven Dials Jazz Club opened its doors in 1980 as a venue for live music in Covent Garden, London. It hosted a range of artists and styles of jazz and began to attract a regular audience. Starting in 1983, a series of saxophone festivals was held on the premises each year.

It started in the Seven Dials Community Centre on Shelton Street and later moved nearby to 46 Earlham Street, opposite the Donmar Warehouse. In 1986 it moved to the Black Horse, 6 Rathbone Place, Fitzrovia.[1]

History

Early days

During the mid-1970s the Seven Dials Community Centre, in Shelton Street, London WC2, was briefly used by the Jazz Centre Society (founded 1969)[2] as a venue for music. After some building alterations, the Seven Dials Jazz Club reopened on a regular basis in July 1980, but soon met with financial difficulties. In 1982, saxophonists Evan Parker and Dave Chambers, on behalf of local musicians, approached Matthew Wright of Collets Jazz & Folk Shop (soon to transform itself into Ray’s Jazz Shop), Shaftesbury Avenue, to take over and run the club.

It was at this time, during a visit by Matthew Wright to Ronnie Scott’s club, that Scott mentioned to him that he had heard he had taken over the Dials. Wright replied in the affirmative and extended an invitation that any time the club owner and saxophonist wanted to drop by, his name would be on the door as his guest. "And I suppose you’d like me to reciprocate?" was Scott's characteristically deadpan riposte, the difference between the two venues in terms of profile not escaping the attention of both men.

Artists and styles

The Dials soon started to pick up and attracted a regular audience with a wide range of artists and styles of jazz. Jazz-rock was represented by the Dick Morrissey-Jim Mullen group, Ian Carr’s Nucleus and the Latin band Cayenne. African and Township Jazz were featured and Julian Bahula's Jazz Africa, Dudu Pukwana and Zila, Brian Abrahams' District Six and the explosive bands of Louis Moholo were all regular attractions. South Africa trumpeter Hugh Masekela dropped by on one occasion he was in town and sat in to play.

The "freer" end of the music included Paul Rutherford, Mike Osborne, Evan Parker, Barry Guy, John Stevens, Howard Riley, Phil Wachsmann, Phil Minton, Lol Coxhill, and Roger Turner among others. Other groups featured on included groups headed by bop drummer Tommy Chase, Clark Tracey, Alan Skidmore, Elton Dean, Don Weller, John Taylor, Don Rendell and the Lennie Tristano-influenced saxophonist, Chas Burchall.

Although the club had a reputation for modern players, New Orleans style trumpeter Ken Colyer performed, as Wright widened the musical policy, whilst retaining the improvisational element. The hugely respected folk singer, Frankie Armstrong, appeared with percussionist Ken Hyder’s group, and Blues bands were also booked: Rolling Stones pianist Ian Stewart’s all-star Rocket 88, Jimmy Roche and singer Carol Grimes.

Kate and Mike Westbrook’s Brass Band made appearances, as did the American pianist/guitarist/"vout" vocalist, Slim Gaillard. Wright had recently written an article about Gaillard for Collusion magazine, and the two had struck up a close friendship after Gaillard appeared on the London jazz scene and settled in London.

The policy of stretching the boundaries was exemplified by two evenings that featured established post-bop tenor saxophonist Bobby Wellins with "free" player Evan Parker. The first meeting saw Wellins in an improvisational setting with Parker’s group; a few weeks later, Parker guested with Wellins’ more straight-ahead quartet. Both occasions were a success. As well as established names, the club also promoted up-and-coming musicians, such as the emerging talents of Annie Whitehead, Alan Barnes, Simon Pickard, Veryan Weston, Tim Whitehead, Django Bates, Mervyn Africa and Ruthie Smith’s all female group, The Guest Stars.

The club hosted small ‘festivals’. It was the venue for the first of "Four Nights of Canadian Improvised Music in London", in which visiting reed player and editor of CODA Magazine, Bill Smith, with fellow Canadian saxophonist Maury Coles, played with local musicians Paul Rutherford (trombone), Paul Rogers (bass) and Nigel Morris (drums).

The saxophone festivals

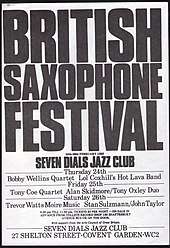

In 1983 was the first of the venues Saxophone Festivals, supported by the Arts Council of Great Britain. Presented over 3 nights, the first coupled Bobby Wellins’ Quartet with Lol Coxhill’s Hot Lava Band; the following night, Tony Coe’s Quartet and the Alan Skidmore/Tony Oxley Duo; the final night Stan Sulzmann and John Taylor opened the proceedings before the climax of Trevor Watts’ Moire Music. This was a ten-piece band that included four saxophonists and two violinists, and it played to a packed house. Lol Coxhill was MC, a role in which he had become accustomed at festivals, and as Jack Massarik pointed out in his review in the London Evening Standard (28 February 1983), Coxhill explained wryly: "I first got into this as a ruse to be near my idols, but things didn’t go quite as planned when I turned out to be one of the finest musicians in the world." Massarik continued, "The ice thus broken, he retired to 'sit at the feet of the master' as (Tony) Coe did indeed give a magisterial performance both on tenor sax and clarinet."[3]

The following year’s Saxophone Festival included Sulzmann, Parker, Peter King, Ray Warleigh, Kathy Stobart (with vibes player Bill Le Sage), Don Weller, Art Themen and the duo of Elton Dean and pianist Keith Tippett. The structure and juxtaposition of styles was always important to Wright, to reflect the breadth and variety of the genre.

John Fordham wrote in The Guardian newspaper in June 1984: “There was a time when saxophone players as far apart on the spectrum as Stan Sulzmann and Evan Parker would never be able to appear in the same club let alone share the microphone. Both events transpired on the first night of the Seven Dials excellent saxophone festival.”[4]

Later in the year, Wright took more of a back seat, due to commitments following the changeover of Collets into Ray’s Jazz Shop, and he handed the reins to American drummer Joe Gallivan, although his right-hand man, well-known Soho jazz character, Jackie Docherty, continued to man the door.

The regular listings programme contained woodcut-style pen and ink drawings by illustrator Clifford Harper.[5]

References

- "Page 5", Jazz Journal International, 39, 1986

- The Jazz Site Archived 2011-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Jack Massarik (1983) Jazz. London Evening Standard. 28 February 1983.

- John Fordham (1984), "Evan Parker", The Guardian, June 1984.

- Agraphia