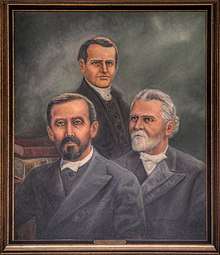

Seth Cook Rees

Seth Cook Rees (August 6, 1854 to May 22, 1933) was a leading figure in the “holiness movement," co-founding the International Holiness Union and Prayer League, and, following a schism with the Church of the Nazarene, founding the Pilgrim Holiness Church, a forerunner of the Wesleyan Church.

.jpg)

Early life and ministry

Rees was born in Westfield, Indiana to a Quaker family.[1] For his formal education, Rees attended the town's Friends Academy.[1][2]

In March 1873, Rees "converted," undergoing a spiritual awakening.[1] The following August, Rees commenced his career as an evangelical preacher, giving his first sermon atop a mound of dirt.[1][2] In 1876, Rees married Hulda Johnson, a tenant of his uncle.[2]

In 1883, Rees underwent a second "calling" by the Holy Spirit. He took on the life of an itinerant missionary, preaching to the Modoc, Cherokee and Peoria peoples in Kansas, before returning to the life of a pastor in Michigan.[2]

In 1894, Rees began serving as pastor at the independent Emmanuel Church in Providence, Rhode Island. During his two years as pastor more than a thousand people were "saved" at the church. He organized his followers in a system of six “corps”: the Slum Corps, the Sailor Corps, the Prison Corps, the City Mission Corps, the Hospital Corps, and the Open Air Corps.[3] Rees' military-style form of organization underscored the active engagement with the poor and downtrodden, a central tenet of Rees' philosophy.[4]

After two years of his Providence revival, Rees again took to the road to preach. With his boisterous preaching style, he was dubbed the "Earthquaker."[2][3] While in Cincinnati, he met Martin Wells Knapp.[2][3] With Knapp, Rees formed the International Holiness Union and Prayer League in 1897, an organization led by Rees until 1905.[5] The Prayer League emphasized holiness, healing, evangelism, and premillennialism.[5] In this regard, the League was heavily influenced by the “fourfold gospel” of A. B. Simpson, founder of the Christian & Missionary Alliance, which emphasized of Salvation, Sanctification, Healing and the Second Coming.[1][3]

Rees' views were crystallized in an 1897 book titled The Ideal Pentecostal Church.[6][7][4]

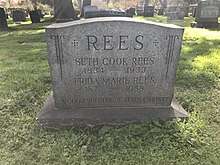

In 1898, Rees' wife Hulda passed away. The following year, in November 1899, Rees married 17-year-old, Swedish-born, Frida Marie Stromberg of Providence, Rhode Island.[1][2] For their honeymoon, the two held a revival in South Carolina attended by more than 1,000 "seekers."[2]

By 1901, Rees had set up a ministry in Chicago, where he established his first "rescue home" for girls and women.[2] Rees eventually launched a total of ten such homes across the country.[2] In 1905, while still in Chicago, Rees published Miracles in the Slums, a book intended to inspire young women to rise above prostitution.[8]

Move to Pasadena

In 1908, Rees moved west, settling in Pasadena, California, a place that Rees regarded as "the fairest and best," and which served as his home until his death 25 years later.[1]

After settling in Pasadena, Rees commissioned the renowned Santa Barbara architect Francis W. Wilson to design a home in Pasadena's Normandie Heights neighborhood. The house exhibits typical Arts and Crafts features including clapboard siding on the first floor and wood-shingle wall cladding on the second floor and gables; wood double-hung and casement windows with divided lights; a wide wood front door with a large oval window; Arroyo-stone foundation, porch, columns and chimney; vented gables; exposed rafters on the horizontal portions of the roof and triangular braces on the sloping roofs. In light of the home's architectural significance, it has been designated an historical landmark by the City of Pasadena.[9]

Later that year, after a particularly energetic guest sermon at the First Church of Nazarene in Los Angeles, Rees caused a bit of local scandal by departing the church and leaving his sleeping son Paul behind. According to a newspaper account, "[w]hen the boy awoke he was frightened and began to scream lustily, but the door was locked and his rescue was delayed." When Rees returned home, he recalled having the boy and promptly telephoned the pastor's wife, learning that the boy was safe.

Church of the Nazarene

In 1912, Phineas Bresee, founder and a General Superintendent of the Church of the Nazarene, called upon Rees to serve as the pastor of the newly formed Nazarene University in Pasadena.[1] Bresee named H. Orton Wiley as the dean of this new institution.[1][3]

In January 1914, Rees called a "judgment day meeting" at the University, exhorting students to prepare by confessing to one another as if Christ's return were imminent.[1][10] This resulted in a frenzied and ongoing revival, with the student body developing a profound attachment to Rees and Wiley.[10] However, a deep rift developed between Reese and Wiley, on a group of faculty members, led by Professor A. J. Ramsay and A. O. Hendricks, who opposed the "freedom of the spirit."[10] Over the following years, charges and counter-charges were leveled.[10]

After Bresee died in 1915, and Wiley resigned from the school the following year, Rees found himself isolated. When ecclesiastical charges that had been routinely quashed by Bresee were renewed against Rees in May 1916, protocol was followed and a “trial” was set for May 29 at the First Church of the Nazarene, then located at Sixth and Wall Streets in Los Angeles. While such trials were supposed to be conducted behind closed doors, Rees reached out to supporters through the local press, promising a “sensation.”[11] When the trial began, a raucous crowd of two hundred supporters had assembled as “character witnesses” outside the church. The throng caused such a commotion that the trial committee agreed to admit the crowd to the auditorium; however, they were not allowed access to the proceedings, and Rees "walked out" in protest. In the end, the committee of elders was unable to reach consensus and Rees was acquitted.[12]

But the die had been cast. On February 25, 1917, a Nazarene executive showed up at a Sunday morning service to excommunicate Rees and order the dissolution of his congregation as a Nazarene church.[1][13] In a formal letter, the district superintendent claimed that the move was required due to "intolerable conditions" within the church.

Pilgrim Holiness Church

Following his expulsion, Rees formed a small denomination known as the Pilgrim Church, and began circulating a periodical known as The Pilgrim.[1] The group then formed a Bible training school and began sending missionaries to locations such as Mexico.[1][2]

In 1922, Rees merged with congregation with the International Holiness Church in order to form the Pilgrim Holiness Church.[1] In 1926, Rees was elected general superintendent, sharing the leadership of the church with two others.[2] In 1930, the church was reorganized, and Rees was called upon to hold undivided leadership.[2]

Later, in 1968, the Pilgrim Holiness Church merged with the Wesleyan Methodist religious body to form the Wesleyan Church.[2]

Later years and death

In 1925, Rees began a lengthy tour of the world, visiting Europe, the Holy Land, China and Japan, and chronicling his journey with dispatches to his followers.[1]

By 1932, Rees was in ill health, and could often not venture beyond the parlor of his Pasadena home to receive visitors.[1][2] Rees died at home, in the presence of his son, the pastor Paul S. Rees, in the early morning hours of May 22, 1933, whispering the words "I'm almost home" and "pass[ing] from peace to greater peace" "[j]ust as the day was beginning to break cloudlessly over the mountains of which he was so untiringly fond."[1] Rees' funeral took place two days later in a packed auditorium at Pilgrim Tabernacle in Pasadena.[1]

Rees is buried in Mountain View Cemetery just outside Pasadena.[1][14]

References

- Rees, Paul S. (1934). Seth Cook Rees, The Warrior Saint. Indianapolis, Indiana: The Pilgrim Book Room.

- Haines, Lee. "Martin W. Knapp & Seth C. Rees: Two Pilgrims' Progress" (PDF). The Wesleyan Church. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- "Pilgrim Holiness Church Founding". www.drurywriting.com. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- Hynson, Leon O. (July 1995). "Called to Be Pilgrims". Methodist History. 33:4: 207–225.

- "Events | Pilgrim Holiness Church | Timeline | The Association of Religion Data Archives". www.thearda.com. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- Rees, Seth Cook (1897). The Ideal Pentaeostal Church. Cincinnati, Ohio: The Revivalist Office.

- "PRIMITIVISM IN THE AMERICAN HOLINESS TRADITION". www.lcoggt.org. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- Rees, Seth Cook (1905-05-20), English: Full text of book (PDF), retrieved 2018-01-08

- "CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL RESOURCES INVENTORY DATABASE". pasadena.cfwebtools.com. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- Smith, Timothy (2006-08-14). "Called Unto Holiness. The Story of The Nazarenes: The Formative Years" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- English: Pasadena Star News (PDF), 1916-05-27, retrieved 2018-01-08

- Herald, Los Angeles (1916-05-30), English: Los Angeles Herald; May 30, 1916; Issue nr: 181; Volume: XLII (complete copy) (PDF), retrieved 2018-01-08

- "Did the Pilgroms Split from the Nazarenes?". www.drurywriting.com. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- "Interment Locations | Mountain View Mortuary & Cemetery - Altadena, CA". www.mtn-view.com. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

External links

![]()