Sesbania punicea

Sesbania punicea (Spanish gold, rattlebox, or scarlet sesban) is an ornamental shrub that produces reddish-orange flowers, has deciduous leaves, and grows to 15 feet high. This plant has a high demand for water, and thrives in swamps or high-moisture areas. It also requires a mildly acidic soil to grow, ranging between 6.1 and 6.5 pH.[1][2]

| Sesbania punicea | |

|---|---|

| |

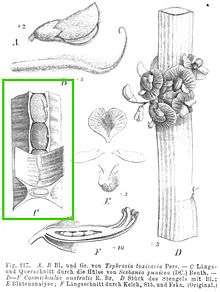

| Fruit or seed pods of the species Sesbania punicea | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | Sesbania punicea |

| Binomial name | |

| Sesbania punicea | |

Distribution

This species is native to Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. It has spread to parts of Africa, other parts of South America, and many coastal southern United States. Due to its high demand for water, this species is often found at marshy shorelines. It also forms dense thickets and thrives in disturbed areas.[1][3][4]

Taxonomy

The genus Sesbania is within the larger family Fabaceae. The Fabaceae are divided into three subfamilies:

- Mimosoideae (80 genera and 3,200 species)

- Caesalpinioideae (170 genera and 2,000 species)

- Faboideae (470 genera and 14,000 species)

- Caesalpinioideae (170 genera and 2,000 species)

The genus Sesbania falls under the subfamily Faboideae, which has the greatest amount of diversity within the family Fabaceae. The subfamilies Mimosoideae and Faboideae are largely monophyletic, whereas the subfamily Caesalpinioideae is considered paraphyletic.[5]

Habitat and ecology

The flowers begin to appear in the late spring and persist until the autumn. In the United States, the blooming period for this species is between June and September, whereas in South Africa it is between November and January.[6][7]

When the carpellous structures dry out, they are distributed close to the base of the parent plant when found inland. Commonly, these plants are found near waterways due to the effective seed dispersal technique by moving water. The seeds of this plant have impermeable seed coats, which allow the survival of the seeds when dispersed by waterways. This impermeable quality of the seed coat was found to be caused by callose.[8] These seeds require scarification before they are able to germinate, and germinated seedlings are commonly found along moist rivers and smaller tributaries. Seed dispersal is not performed by animals due to the plants' toxic characteristics. This species has also been commonly found near roadsides, hypothetically due to seeds being present in imported soil used for the construction of roads. This species is known to be shade-tolerant, allowing seedling growth under shady conditions. Once seedlings have grown for three months, they can potentially produce flowers and seeds, although flowering most commonly occurs once the seedlings become two years of age. This plant is capable of surviving freezing conditions, but not for prolonged periods of time .[7]

Morphology

This shrub has deciduous leaves that are alternate and compound with between five and 20 pairs of elliptical leaflets on a single stalk. The leaf margins are commonly entire, with little or no serration. Each leaflet is oblong in shape and ends in a pointy tip . The leaves contain stipules that are usually inconspicuous. These plants produce both fruits and flowers in a drooping fashion at the tips of these stalks. The branches of this shrub are rather thin, and are originally green, but turn a darker red brown when they mature. The bark varies from a gray brown to a red brown with obvious horizontal lenticels.[6][9][10]

Sketch of S. punicea in 1891 |

Herbaceous habit of S. punicea |

Flowers and fruit

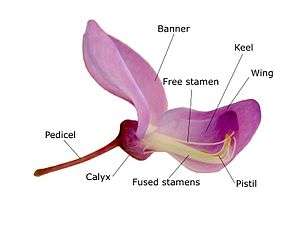

The flowers are shaped like pea flowers, 2–3 cm long, and are commonly a red-orange or red-purple color. These flowers are often found in a raceme fashion. Characteristic of the family Fabaceae, this species has five fused sepals and five free petals. The flower always contains 10 stamens, sometimes with various combinations of fused filaments. The ovary is superior and the style is often curved. Characteristic of the subfamily Faboideae, these flowers are zygomorphic and have a specialized structure. The upper petal is referred to as the banner, and encapsulates the petals when they are in the bud. The two adjacent flowers, called the wings, overlap the bottom two petals. The bottom petals are often fused at the apex, forming a structure called the keel. The flowers often appear outlandish and "showy" because they are most commonly pollinated by insects, so use these tactics to appeal to pollinators. [3]

Sesbania punicea fruit |

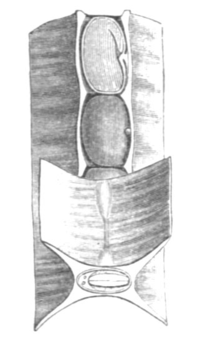

Illustration of placentation of seeds inside the pods of S. punicea |

The fruits are large pea pods compartmentalized into four, and appear as if they have shrunk slightly due to drying These fruits are dehiscent and dry out as they become mature. Each fruit can contain between five and 10 seeds, which are only dispersed when the pod dries out and opens up. The number of pods found on a single plant depends on age and growing conditions of the plant. On average, a single plant can produce 100-300 pods. When the pods first emerge on the plants and are not yet fully mature, they are a yellow or green color. As the season progresses, these pods become a darker green color, eventually becoming a dismal brown . These seedpods often stay on the plant far into the winter, and the seeds inside create a distinct rattling sound when they are shaken by the wind, giving the plant its common name of “rattlebox”.[3][7][9][11]

Usage and economic importance

These plants are seen to have an ornamental value due to the beautiful red flowers the plant produces. The poisonous characteristic is dangerous to local bird and mammal populations, and this ability of poisoning any potential threats to the Sesbania population allows it to flourish as an invasive species.[4] This species has been reported as invasive in many of the southern United States such as Virginia, California, Texas, and Florida. This shrub can often form dense thickets.[6] This species is actively replacing native species of plants in riparian areas, which is taking food resources away from the local wildlife.[12] In addition to displacing native plants and affecting local wildlife, this species contributes to riverbank erosion and flooding in areas where it persists.[13]

Although this has no known economic or medicinal uses, its close relative S. virgata does.[10] S. virgata has been used to control soil erosion, rehabilitate disturbed areas, and revitalize riparian habitats.[10] Juice made from the leaves of this plant have been shown to reduce the response to painful stimulation and inflammatory edema in mice.[10]

Food

This species has been declared a noxious weed and/or seed in the United States. It has been identified as noxious in the aquatic, terrestrial, and seed forms.[4] Any animal that or human who ingests this plant or seed can become very sick and may experience symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, respiratory failure, or death.[9] The compounds contained in this plant that make it so toxic are the saponic glycosides.[9]

Management

The root systems of young S. punicea plants are not very extensive and the soil is loose under waterlogged conditions, so these plants can be removed by hand or by using some simple garden tools.[3] Trees with larger trunks must be cut and treated with the herbicide glyphosate and/or triclopyr.[3] If they are found in standing water, the stem can be cut to below the water level. Simply flooding the area will not kill them.

In some instances, biological controls have been used to mitigate this species from spreading so rapidly. The South American apionid weevil, Trichapion lativentre, was introduced to South Africa in the late 1970s. This weevil has now dispersed over most of the range of S. punicea. The adult weevils feed on the leaves and lay single eggs in premature flower buds. The larvae then feed on the stamens and carpels of the flower and continue to pupate in the hollow husks of the buds. Due to these herbivorous interactions, this weevil has shown to successfully mitigate the rapid spread of S. punicea in South Africa.[14]

References

- "Sesbania punicea." PLANTS Profile. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, n.d. Web. 31 Mar 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Sesbania punicea". University of Florida, IFAS. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- "Invasives Database: Sesbania punicea". TexasInvasives.org. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- "Sesbania punicea". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- 'The Legume Phylogeny Working Group (LPWG).', 2017, A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny , Taxon , vol. = 66 , number = 1 , pages = 44–77 , http://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/iapt/tax/2017/00000066/00000001/art00004

- "Sesbania punicea Fact Sheet". VT Forest Biology and Dendrology. VT Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation.

- "Sesbania punicea (Fabaceae)". EPPO. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Bevilacqua, L. "'Callose' in the impermeable seed coat of Sesbania punicea". Oxford Journals. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Alice, Russell. "Poisonous Plants of North Carolina". Department of Horticulture Science. North Carolina State University. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- Nader de León, Alejandro. "Uruguay's wildlife and Natural sanctuaries". Blogger.com. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "Sesbania punicea, Sesbania tripetii, Daubentonia tripetii". TopTropicals.com. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- "Sesbania punicea". U.S. Department of the Interior: Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- "Sesbania punicea". California Invasive Plant Council. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- Hoffmann, J.H.; Moran, V.C. (1989). "Novel Graphs for Depicting Herbivore Damage on Plants: The Biocontrol of Sesbania punicea (Fabaceae) by an Introduced Weevil". Journal of Applied Ecology. 26 (1): 353–360. doi:10.2307/2403672. JSTOR 2403672.