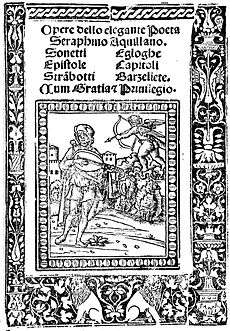

Serafino dell'Aquila

The Italian poet and musician Serafino dell'Aquila or Aquilano is alternatively named Serafino dei Ciminelli from the family to which he belonged. He was born in what was then the Neapolitan town of L'Aquila on 6 January 1466 and died of a fever in Rome on 10 August 1500. As a writer he was one of the foremost of the stylistic followers of Petrarch and his work was later influential on both French and English Petrarchan poets.

Life

Serafino’s parents were Francesco Ciminelli and Lippa de' Legistis. In 1478 he was taken to Naples by his maternal uncle Paolo de' Legistis, secretary to Antonio de Guevara, Count of Potenza, and became a page in his court. There he studied music and possibly composition, at first with the visiting Flemish musician Guillaume Garnier and then Josquin des Préz. On the death of his father in 1481 he returned to Aquila, where he gained fame for performing the poetry of Petrarch to his own accompaniment on the lute. Leaving for Rome in 1484, he entered the service of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza and formed a connection with the literary circle of the Papal Apostolic Secretary Paolo Cortese, where he became friendly with Vincenzo Colli (il Calmeta), his eventual biographer.

Having caused offence by castigating the vices of the Papal court in a satirical composition, he left his patron to settle in Naples again. There he became a member of the Academy of Pontano, where he associated with Jacopo Sannazaro, Pier Antonio Caracciolo and Benedetto Gareth (il Chariteo), whose eight-lined strambotti he took as model for his own. In 1494, however, he had to quit the city at the onset of warfare. During the next few years he visited Urbino, Mantua, Milan and other northern Italian cities, performing at their courts. In 1500 he returned to Rome, where he was made a Knight of Malta but only survived a few months to enjoy that honour. After his death from fever, he was buried in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo.[1]

Poetry

Because Serafino chanted his poems to his own lute accompaniment and often improvised the words as part of his performance, texts were taken down by others at the time and spread in manuscript, or sometimes in print. Definite attribution to him was therefore difficult later, as was establishing a definitive text. It was not until after his death that a first edition of his works appeared from Rome in 1502, to be followed by some twenty more in the next ten years alone.[2] Ultimately they ran into many more during the time his reputation was high. Of the 391 poems ascribed to him, 261 are strambotti and 97 are sonnets.

A collection of commendatory sonnets and other verses dedicated to Serafino was published in 1504. In the same year, Calmeta’s biography of him was published from Bologna and, along with some of the commendatory verses, introduced various collections of his poetry over the years. He and those with whom he associated had been drawn to Petrarch as a model and had cultivated in particular his use of the conceit, sometimes to an extravagant degree. The style was deprecated by Pietro Bembo and taste for it had waned by 1560, never really to revive.[3]

Serafino’s work was used as a model in various ways by 16th-century French and English writers. His sonnet Si questo miser corpo t’abandona (if this unhappy body leaves you) was adapted into the rondeau S’il est ainsi que ce corps t’abandonne (if it happens that this body leaves you) by Jean Marot. A little later Thomas Wyatt adapted the Marot rondeau into English as “If it be so that I forsake thee”.[4] But Wyatt was also to translate or adapt Serafino’s work directly, being especially drawn to his use of the epigramatic strambotto, a form he introduced into English verse.[5] For the extravagant image of the breaking heart being like an exploding cannon, he is only indebted to Serafino for the idea in his “The furious gonne in his rajing yre”.[6] In “Thou slepest ffast” two strambotti are adapted to make a single epigram, while other poems are a little more closely translated.[7]

Serafino and fellow Petrarchans have also been claimed as an influence on the French poet Maurice Scève,[8] and in England twelve later sonnets by Thomas Watson have been identified as versions of Serafino’s.[9]

References

- Magda Vigilante, “Ciminelli, Serafino”, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 25 (1981)

- Francesca Bortoletti, “Serafino Aquilano and the Mask of Poeta”, Voices and Texts in Early Modern Italian Society, Routledge 2017

- Giada Viviani, “Serafino Aquilano” in the Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies, Routledge 2007, pp.1731-2

- J. Christopher Warner, The Making and Marketing of Tottel’s Miscellany, Routledge 2016, p.60

- Patricia Thomson, Sir Thomas Wyatt and His Background, Stanford University 1964, ch. 7, “Wyatt and the school of Serafino”, pp.209-237

- George Frederick Nott’s edition of Wyatt’s poems, London 1816, Vol. 2, p.557

- Annabel M. Endicott, “A Note on Wyatt and Serafino D'Aquilano”, Renaissance News, University of Chicago 1964, Vol. 17. 4, pp. 301-303

- I.D. McFarlane, introduction to Scève’s Délie, Cambridge University 1966, pp.26-7

- Sidney Lee, “Thomas Watson”, Dictionary of National Biography 1900