Senate Square, Helsinki

The Senate Square (Finnish: Senaatintori, Swedish: Senatstorget) presents Carl Ludvig Engel's architecture as a unique allegory of political, religious, scientific and commercial powers in the centre of Helsinki, Finland.

Senate Square and its surroundings make up the oldest part of central Helsinki. Landmarks and famous buildings surrounding the square are the Helsinki Cathedral, the Government Palace, main building of the University of Helsinki and the Sederholm House, the oldest building of central Helsinki dating from 1757.[1]

Construction

In the 17th and 18th centuries it was the location of a graveyard.[2] In 1812 Senate Square was designated as the main square for the new capital of Helsinki in the city plan designed by Johan Albrecht Ehrenström.[3] The Palace of the Council of State (or Government Palace) was completed on the eastern side of the Senate Square in 1822. It served as the seat of the Senate of Finland until it was replaced by the Council of State in 1918, and now houses the offices of the Prime Minister of Finland and the cabinet. The main University building, on the opposite side of the Senate Square, was constructed in 1832.[4]

The Helsinki Cathedral on the northern edge of the Senate Square was Engel's lengthiest architectural project. He worked on it from 1818 until his death in 1840. The Helsinki Cathedral — then called the Church of St. Nicholas — dominates the Senate Square, and was finalized twelve years afters Engel's death, in 1852.[5]

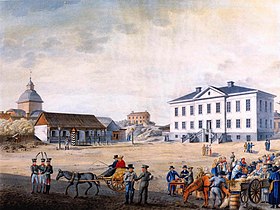

Engel's 1816–1818 watercolor painting of the old square that was located at the southeast part of the current square. On the right is the town hall and on the left the guard house, behind of which is the old Ulrika Eleonora church.[6]

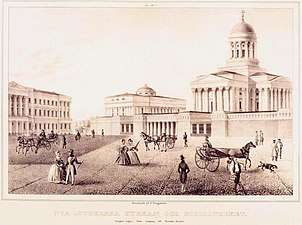

Engel's 1816–1818 watercolor painting of the old square that was located at the southeast part of the current square. On the right is the town hall and on the left the guard house, behind of which is the old Ulrika Eleonora church.[6] Lithograph of the square from 1838. The guard building in front of the cathedral was demolished in the 1840s and replaced with the large steps.[7]

Lithograph of the square from 1838. The guard building in front of the cathedral was demolished in the 1840s and replaced with the large steps.[7] Sederholm House, 1757, the oldest building of central Helsinki at the southeast corner of the square

Sederholm House, 1757, the oldest building of central Helsinki at the southeast corner of the square Government Palace, 1822

Government Palace, 1822 Main Building of University of Helsinki, 1832, in its current facade

Main Building of University of Helsinki, 1832, in its current facade Helsinki Cathedral, 1830–1852

Helsinki Cathedral, 1830–1852

Statue of Alexander II

A statue of Emperor Alexander II is located in the center of the square. The statue, erected in 1894, was built to commemorate his re-establishment of the Diet of Finland in 1863 as well as his initiation of several reforms that increased Finland's autonomy from Russia. The statue comprises Alexander on a pedestal surrounded by figures representing law, culture, and peasants. The sculptor was Walter Runeberg.[8]

During the Russification of Finland from 1899 onwards, the statue became a symbol of quiet resistance, with people protesting against the decrees of Nicholas II by leaving flowers at the foot of the statue of his grandfather, then known in Finland as "the good tsar".[9]

After Finland's independence in 1917, demands were made to remove the statue. Later, it was suggested to replace it with the equestrian statue of Mannerheim currently located on Mannerheimintie in front of the Kiasma museum. Nothing came of either of these suggestions, and today the statue is one of the major tourist landmarks of the city and a reminder of Finland's close relationship with Imperial Russia.[9]

.jpg) Reveal of the statue of Alexander II, 29 April 1894

Reveal of the statue of Alexander II, 29 April 1894_tornista_etel%C3%A4%C3%A4n_-_N505_(hkm.HKMS000005-0000011a).jpg) View from the tower of the cathedral towards southwest in 1909

View from the tower of the cathedral towards southwest in 1909_tornista_kaakkoon._vas_-_N504_(hkm.HKMS000005-0000011b).jpg) View to the southeast in 1909

View to the southeast in 1909.jpg) Parade of the White Guard on 16 May 1918 after the Battle of Helsinki

Parade of the White Guard on 16 May 1918 after the Battle of Helsinki Demonstration by the unions at the square during a general strike in 1956

Demonstration by the unions at the square during a general strike in 1956

Contemporary role

Today, the Senate Square is one of the main tourist attractions of Helsinki. Various art happenings, ranging from concerts to snow buildings to controversial snow board happenings, have been set up on the Senate Square.[10] In Autumn 2010 a United Buddy Bears exhibition with 142 bears was displayed on the historic square.[11][12]

Digital carillon music (Finnish: Senaatintorin ääni) is played daily at 17:49 at the Senate Square. The sound installation was composed by Harri Viitanen, composer and organist of Helsinki Cathedral, and Jyrki Alakuijala, Doctor of Technology. The optimal listening position is at the proximity of the Square's central monument, the bronze statue of Alexander II.[13]

Several buildings near the Senate Square are managed by the government real estate provider, Senate Properties.[14] At the northwest corner there are four short pillars erected each winter to protect the memorial plate of the Ulrika Eleonora church from snow plows.[2][15]

The site aspires to get on the World Heritage Site but a single building in its southwest corner prevents it.[16][17]

The red building on the left breaks the architectural style of the square

The red building on the left breaks the architectural style of the square Aerial photograph of the square towards the sea in 2015

Aerial photograph of the square towards the sea in 2015 Trams travel on the eastern and southern sides of the square, and in this photograph special older models are being used

Trams travel on the eastern and southern sides of the square, and in this photograph special older models are being used

The square is often a spot for artworks and events like this environmental-awareness raising plastic bag octopus during Helsinki Night of the Arts 2016

The square is often a spot for artworks and events like this environmental-awareness raising plastic bag octopus during Helsinki Night of the Arts 2016 Snow sculpture version of the old Ulrika Eleonora Church being constructed on the square in 2000 (also done once before in 1997)[20]

Snow sculpture version of the old Ulrika Eleonora Church being constructed on the square in 2000 (also done once before in 1997)[20] Red Bull City Flight snowboarding event at the square in 2001

Red Bull City Flight snowboarding event at the square in 2001 Open-air food court in 2020

Open-air food court in 2020

In popular culture

Film

- American actor and film director Warren Beatty filmed scenes from his film Reds (1981) on the square — Helsinki playing the role of St. Peterburg — but without showing the Cathedral.[21]

- The title sequence of John Huston's The Kremlin Letter (1970) was filmed over the square at night, including the silhouette of the Cathedral.[22][23]

- Snowy night scenes from Jim Jarmusch's film Night on Earth (1991) were filmed on the square, but given the impression that there is a traffic roundabout at the center.[24]

Music

References

- "Helsingin kaupunginmuseo, Sederholmin talo". Stadissa. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Pajunen, Lauri (28 July 2020). "Senaatintorin salaisuudet". Iltalehti. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- "Senaatintori ympäristöineen". Valtakunnallisesti merkittävät rakennetut kulttuuriympäristöt RKY. 22 December 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Hasu, Kirsi (4 March 2020). "Senaatintori – koko Suomen pää ja sydän". Helsinki. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Perälä, Reijo (12 April 2018). "Helsingin tuomiokirkko nousi vallan symboliksi ja maksoi miljoona ruplaa". Yle. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Senaatorin Historia". Visit Sveaborg. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- "Kirkon tarina". Helsingin Tuomiokirkko. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Senaatintori ja Aleksanteri II:n patsas". Eduskunta. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Roiha, Juha (24 September 2019). "Venäjän keisarin patsas herättää turisteissa ihmetystä – Miksi se on yhä keskellä Helsinkiä?". Yle. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Saariaho, Jari (6 April 2001). "Kääk, lautailua Senaatintorilla!". City. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "United Buddy Bears in Helsinki". United Buddy Bears. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "'Buddy Bears' Take Over Senate Square". Yle. 30 August 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Helsinki.fi Archived 2010-08-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "Helsingin nähtävyyksiä". Kylatalo. 5 May 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Memorial to the Ulrika Eleonora Church". HAM Helsinki. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Manninen, Antti (27 October 2002). "Senaatintori ehkä Unescon suojelulistalle".

- Manninen, Antti (15 September 2015). "Senaatintori haluttiin Unescon maailmanperintölistalle, mutta yksi rakennus vaaransi suunnitelman".

- Zitting, Marianne (26 November 2018). "Joulu valtaa Senaatintorin! Tuomaan markkinoilla pääsee saunaan ja vegekinkkubingoon". Iltalehti. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- "Info". Tuomaan Markkinat. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- "Minä vuosina Helsingin Senaatintorille rakennettiin lumikirkko?". Kysy. 13 October 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Valleala, Siru (23 January 2020). "Seksin Samuraiksi ja Hollywoodin prinssiksi kutsuttu Warren Beatty on urallaan kuvannut elokuvaa myös Suomessa – tältä kuvauksissa näytti Senaatintorilla". Ilta-Sanomat. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Suomi Venäjänä elokuvissa". Elokuvapolku. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Römpötti, Harri (8 June 2018). "Helsinki Hollywood-näyttelijänä – nämä paikat Helsingissä ovat esittäneet Neuvostoliittoa amerikkalaisissa elokuvissa". Helsingin Sanomat. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Lehtovuori, Panu (2010). Experience and Conflict: The Production of Urban Space. Gower Publishing. ISBN 9780754676027.

- Rantanen, Miska (2 May 2019). "Maailman kuuluisin takaa-ajojuoksu". Helsingin Sanomat. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

External links