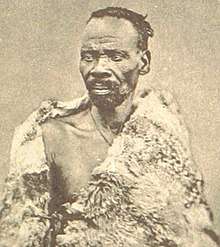

Sekhukhune

Sekhukhune I[lower-alpha 1] (Matsebe; circa 1814 – 13 August 1882) was the paramount King of the Marota, more commonly known as the Bapedi, from 21 September 1861 until his assassination on 13 August 1882 by his rival and half-brother, Mampuru II. As the Pedi paramount leader he was faced with political challenges from boer settlers, the independent South African Republic (Dutch: Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek) the British Empire, and considerable social change caused by Christian missionaries.

| Sekhukhune I | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of the Bapedi | |

| Reign | 21 September 1861 – 13 August 1882 |

| Predecessor | Sekwati I |

| Successor | Kgoloko(regent for Sekhukhune II) |

| Born | Matsebe Unknown date, 1814 |

| Died | (aged 68) |

| Spouse | Legoadi IV |

| Issue | Morwamotshe II |

| House | Maroteng |

| Father | Sekwati I |

| Mother | Thorometjane Phala |

| Religion | African Traditional Religion |

Sekhukhune was the son of Sekwati I, and succeeded him upon his death in 20 September 1861 after forcibly taking the throne from his half-brother and the heir apparent Mampuru II. Sekhukhune married Legoadi IV in 1862, and lived at a mountain, now known as Thaba Ya Leolo,[1] which he fortified.

He fought two wars. The first war was successfully fought in 1876, against the ZAR and their Swazi allies. The second war, against the British and Swazi in 1879 in what became known as the Sekhukhune Wars, was less successful.[2][3]

Sekhukhune was detained in Pretoria until 1881. After a return to his kingdom, he was fatally stabbed by an assassin in 1882, at Manoge.[4] The assassins are presumed to have been sent by his brother and competitor, Mampuru II.[5][6]

Sekhukhune Wars

First Sekhukhune War

On 16 May 1876, President Thomas François Burgers of the South African Republic (Transvaal) declared war against Sekhukhune and the Pedi. Sekhukhune managed to defeat the Transvaal army on 1 August 1876. Bergers' government later launched another attack by hiring the services of the Lydenburg Volunteer Corps commanded by a German mercinary, Conrad von Schlickmann (killed later that year in a Pedi ambush), but it was also repulsed. On 16 February 1877, the two parties, mediated by Alexander Merensky, signed a peace treaty at Botshabelo. The Boers inability to subdue Sekhukhune and the Pedi led to the departure of Burgers in favour of Paul Kruger and the British annexation of the South African Republic(Transvaal) on 12 April 1877 by Sir Theophilus Shepstone, secretary for native affairs of Natal.[7]

Second Sekhukhune War

Although the British had first condemned the Transvaal war against Sekhukhune, it was continued after the annexation. In 1878 and 1879 three British attacks were successfully repelled until Sir Garnet Wolseley defeated Sekhukhune in November 1879 with an army of 2,000 British soldiers, Boers and 10,000 Swazis.[8] On 2 December 1879, Sekhukhune was captured and on 9 December 1879 he was imprisoned in Pretoria.[9]

Aftermath

On 3 August, 1881, the Pretoria Convention was signed, which stipulated in Article 23 that Sekhukhune would be released. Because his capital had been burned to the ground, he left for a place called Manoge. On 13 August 1882, Sekhukhune was murdered by his half-brother Mampuru II, who claimed to be the lawful king. Mampuru was captured by the Boers, tried for murder and hanged in Pretoria in 21 November 1883.[10]

Legacy

After his death, Bopedi (Pedi kingdom) was divided into small powerless units conducted by the native commissioners. His grandson Sekhukhune II in an effort to rebuild the Bapedi kingdom launched an unsuccessful war against the South African Republic. The defeat marked the end of Pedi resistance against foreign forces.[11]

The London Times, which at the time was not known to report on the deaths of African leaders, published an article on 30 August 1882, acknowledging his resistance against the Boers and the British:

“… We hear this morning … of the death of one of the bravest of our former enemies, the Chief Sekhukhune… The news carries us some years back to the time when the name of Sekhukhune was a name of dread, first to the Dutch and then to the English Colonists of the Transvaal and Natal…”.

— The London Times

The Sekhukhune District Municipality in Limpopo Province has been named after him in 2000; the area is also known as Sekhukhuneland. Making him the only African royal to have a district and region named after him.

See also

References

- Du Plessis, E. J. (1973). 'n Ondersoek na die oorsprong en betekenis van Suid-Afrikaanse berg- en riviername: 'n histories-taalkundige studie [An Investigation into the origin and meaning of South African mountain and river names: a historico-linguistic study] (in Afrikaans). Cape Town: Tafelberg. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-624-00273-4.

- "King Sekhukhune". South African History Online. 13 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Kinsey, H.W. (June 1973). "The Sekukuni Wars". Military History Journal. The South African Military History Society. 2 (5).

- "Bapedi Marote Mamone v Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims and Others (40404/2008) [2012] ZAGPPHC 209; [2012] 4 All SA 544 (GNP) (21 September 2012)". www.saflii.org. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- Delius, Peter (1984). The land belongs to us: the Pedi polity, the Boers and the British in the nineteenth-century Transvaal. Heinemann. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-0-435-94050-8.

- Delius, Peter; Rüther, Kirsten (2013). "The King, the Missionary and the Missionary's Daughter". Journal of Southern African Studies. 39: 597–614. doi:10.1080/03057070.2013.824769.

- "South African Military History Society - Journal- THE SEKUKUNI WARS". samilitaryhistory.org. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- "'Sekukuni [sic] & Family' | Online Collection | National Army Museum, London". collection.nam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- "THE SEKUKUNI WARS PART II - South African Military History Society - Journal". samilitaryhistory.org. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- "Bapedi Marote Mamone v Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims and Others (40404/2008) [2012] ZAGPPHC 209; [2012] 4 All SA 544 (GNP) (21 September 2012)". www.saflii.org. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- Malunga, Felix (2000). "The Anglo-Boer South African War: Sekhukhune II goes on the offensive in the Eastern Transvaal, 1899-1902". Southern Journal for Contemporary History. 25 (2): 57–78. ISSN 2415-0509.

Footnotes

- sometimes spelled Sekukuni

Further reading

- Mabale, Dolphin (18 May 2017). Contested Cultural Heritage in the Limpopo Province of South Africa: the case study of the Statue of King Nghunghunyani (MA). University of Venda. hdl:11602/692.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Motseo, Thapelo (22 August 2018). "King Sekhukhune I colourfully remembered". sekhukhunetimes.co.za. Retrieved 4 March 2019.