Life Is a Dream

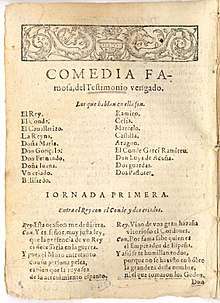

Life Is a Dream (Spanish: La vida es sueño [la ˈβiða es ˈsweɲo]) is a Spanish-language play by Pedro Calderón de la Barca. First published in 1636, in two different editions, the first in Madrid and a second one in Zaragoza. Don W. Cruickshank and a number of other critics believe that the play can be dated around 1630, thus making Calderón's most famous work a rather early composition [1]. It is a philosophical allegory regarding the human situation and the mystery of life.[2] The play has been described as "the supreme example of Spanish Golden Age drama".[3] The story focuses on the fictional Segismundo, Prince of Poland, who has been imprisoned in a tower by his father, King Basilio, following a dire prophecy that the prince would bring disaster to the country and death to the King. Basilio briefly frees Segismundo, but when the prince goes on a rampage, the king imprisons him again, persuading him that it was all a dream.

| Life Is a Dream | |

|---|---|

_03.jpg) Detail from bronze relief on a monument to Calderón in Madrid, J. Figueras, 1878 | |

| Written by | Pedro Calderón de la Barca |

| Date premiered | 1635 |

| Original language | Spanish |

| Subject | Free will, fate, honor, power |

| Genre | Spanish Golden Age drama |

| Setting | Poland |

The play's central themes are the conflict between free will and fate, as well as restoring one's honor (NADV1). It remains one of Calderón's best-known and most studied works, and was listed as one of the 40 greatest plays of all time in The Independent.[4] Other themes include dreams vs. reality and the conflict between father and son. The play has been adapted for other stage works, in film and as a novel.

Historical context

Catholic Spain was the most powerful European nation by the 16th century.[5] The Spanish Armada was defeated by England in 1588, however, while Spain was trying to defend the northern coast of Africa from the expansion of the Turkish Ottoman Empire,[6] and the gold and silver that Spain took from its possessions in the New World were not adequate to sustain its subsequent decades of heavy military expenses. Spain's power was rapidly waning by the time Calderón wrote Life Is a Dream.[7][8]

The age of Calderón was also marked by deep religious conviction in Spain.[9] The Catholic church had fostered Spanish pride and identity, to the extent that "speaking Christian" became, and remains, synonymous with speaking Spanish.[10]

Another current that permeated Spanish thinking was the radical departure from the medieval ideal that royal power resided in God's will, as noted in Machiavelli's The Prince (1532). Francisco Suarez’s treatise On the Defense of Faith (De defensio fidei, 1613) stated that political power resided in the people and rejected the divine rights of kings,[11] and Juan Mariana's On Kings and Kingship (1599) went even further by stating that the people had the right to murder despotic kings.[12]

Amidst these developments during the 16th and 17th centuries, Spain experienced a cultural blossoming referred to as the Spanish Golden Age.[13][14] It saw the birth of notable works of art: Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes (1605), played with the vague line between reality and perception.[15] Lope de Vega, in his play Fuente Ovejuna (1619), talks about a village that rebels against authority.

Synopsis

Act I

.jpg)

After being abandoned by their horses, Rosaura, who is dressed as a man, and Clarín walk through the mountains of Poland without food or anywhere to go for the night. They arrive at a tower, where they find Segismundo imprisoned, bound in chains. He tells them that his only crime was being born. Clotaldo, Segismundo's old warden and tutor, arrives and orders his guards to disarm and kill the intruders, but he recognizes Rosaura's sword as his own that he had left behind in Muskovy (for a favor that he owed) years ago for his child to bear. Suspecting that Rosaura is his child (he thinks she is male), he takes Rosaura and Clarín with him to court.

At the palace, Astolfo, Duke of Muscovy, discusses with his cousin, Princess Estrella (Segismundo's cousin), that as they are the nephew and niece of King Basilio of Poland, they would be his successors if they married each other. Estrella is troubled by the locket that Astolfo wears, with another woman's portrait. Basilio reveals to them that he imprisoned his infant son, Segismundo, due to a prophecy by an oracle that the prince would bring disgrace to Poland and would kill his father, but he wants to grant his son a chance to prove the oracle wrong. If he finds him evil and unworthy, he will send him back to his cell, making way for Astolfo and Estrella to become the new king and queen. Clotaldo enters with Rosaura, telling Basilio that the intruders know about Segismundo. He begs for the king's pardon, as he knows he should have killed them. The king says he should not worry, for his secret has already been revealed. Rosaura tells Clotaldo that she wants revenge against Astolfo, but she won't say why. Clotaldo is reluctant to reveal that he thinks he is Rosaura's father.

Act II

Clotaldo gives Segismundo a sedative that "robs one in his sleep of his sense and faculties" (109), which puts him in a sleep similar to death. In the Royal Palace of the capital city of Warsaw, Clotaldo has learned that Rosaura is a woman; Clarín explains that Rosaura is Princess Estrella's maid but has been going by the name of Astrea. When Segismundo is awakened and arrives at court, Clotaldo tells him that he is the prince of Poland and heir to the throne. He resents Clotaldo for keeping this secret from him for all those years. He finds Duke Astolfo irritating and is dazzled by Estrella's beauty. When a servant warns him about the princess's betrothal to Astolfo, Segismundo is enraged by the news and throws the servant from the balcony.

The king demands an explanation from his son. He tries to reason with him, but Segismundo announces he will fight everyone, for his rights were denied him for a long time. Basilio warns him that he must behave, or he might find out he's dreaming. Segismundo interrupts a conversation between Rosaura and Clarín. Rosaura wants to leave, but Segismundo tries to seduce her. Clotaldo steps up to defend his child, but Segismundo pulls out a dagger threatening to kill him. As Clotaldo begs for his life, Astolfo challenges Segismundo to a duel. Before they proceed, the king sedates the prince again and sends him back to his cell.

|

Segismundo's reflections The king dreams he is a king, |

After recriminating Astolfo for wearing another woman's portrait around his neck, Estrella commands Rosaura (still going by Astrea) to fetch this locket for her. When she approaches Astolfo for the locket, he says he recognized her as Rosaura and refuses to give her the locket, because the portrait inside is hers. Estrella walks in and demands to see it immediately, but, afraid of being discovered, Rosaura says the locket in Astolfo's hand is actually her own, and that he has hidden the one she was sent to fetch. Estrella leaves furious. Meanwhile, Clotaldo sends Clarín to prison, believing that Clarín knows his secret.

Segismundo mutters in his sleep about murder and revenge. When the prince wakes up, he tells Clotaldo about his "dream". Clotaldo tells him that even in dreams, people must act with kindness and justice. When he leaves, Segismundo is left reflecting on dreams and life.

Act III

The people find out that they have a prince and many rebel, breaking him out of his prison tower, although at first they comically mistake Clarin for the prince. Segismundo finds Clotaldo, who is afraid of his reaction. Segismundo forgives him, asking to join his cause, but Clotaldo refuses, swearing allegiance to the king. Back in the palace, everyone prepares for battle, and Clotaldo speaks with Rosaura. She asks him to take Astolfo's life, as he had taken her honor before leaving her. Clotaldo refuses, reminding her that Duke Astolfo is now the heir to the throne. When Rosaura asks what will be of her honor, Clotaldo suggests that she spend her days in a nunnery. Disheartened, Rosaura runs away.

As war nears, Segismundo sees Rosaura, who tells him that she was the youth who found him in his prison and also the woman who he tried to seduce in court. She tells him that she was born in Muscovy of a noble woman who was disgraced and abandoned. She had the same fate, falling in love with Astolfo and giving him her honor before he abandoned her to marry Estrella. She followed him to Poland for revenge, finding that Clotaldo is her father, but he is unwilling to fight for her honor. Rosaura compares herself to female warriors Athena and Diana. She wants to join Segismundo's battle and to kill Astolfo or to die fighting. Segismundo agrees. While soldiers cheer for Segismundo, Rosaura and Clarín are reunited, and the king's soldiers approach.

Segismundo's army is winning the battle. Basilio, Clotaldo and Astolfo are preparing to escape when Clarín is killed in front of them. Segismundo arrives and Basilio faces his son, waiting for his death, but Segismundo spares his life. In light of the Prince's generous attitude, the King proclaims Segismundo heir to his throne. As king, Segismundo decides that Astolfo must keep his promise to marry Rosaura to preserve her honor. At first Astolfo is hesitant because she is not of noble birth, but when Clotaldo reveals that she is his daughter, Astolfo consents. Segismundo then claims Estrella in marriage himself. Segismundo resolves to live by the motto that "God is God", acknowledging that, whether asleep or awake, one must strive for goodness.

Themes and motifs

.jpg)

- Dreams vs. reality

The concept of life as a dream is an ancient one found in Hinduism and Greek philosophy (notably Heraclitus and the famous Platonic Allegory of the Cave), and is directly related to Descartes' dream argument. It has been explored by writers from Lope de Vega to Shakespeare.[17] Key elements from the play may be derived from the Christian legend of Barlaam and Josaphat, which Lope de Vega had brought to the stage.[18] This legend is, itself, a derivation of the story of the early years of Siddharta Gautama, which serves as the basis for the film Little Buddha that illustrates the Hindu-Buddhist concept of reality as illusion.[18]

- Father vs. son conflict

One of the major conflicts of the play is the opposition between king and prince, which parallels with the struggle of Uranus vs. Saturn or Saturn vs. Jupiter in classical mythology.[19] This struggle is a typical representation of the opposition in baroque comedy between the values represented by a fatherly figure and those embodied by the son.[18] An opposition which, in this case, may have biographical elements.[20]

- Honor

The theme of honor is major to the character Rosaura. She feels she has been stripped of her honor, and her aim is to reclaim it. Rosaura feels that both she and her mother were subjected to the same fate. She pleads to Clotaldo about earning her honor back, which he denies and sends her to a nunnery.

- Other motifs and themes

Motifs and themes derived from a number of traditions found in this drama include the labyrinth, the monster, free will vs. predestination, the four elements, original sin, pride and disillusionment.[21][22][23][24]

Analysis and interpretations

Rosaura subplot

The Rosaura subplot has been subjected to much criticism in the past as not belonging to the work. Menéndez y Pelayo saw it as a strange and exotic plot, like a parasitical vine.[25] Rosaura has also been dismissed as the simple stock character of the jilted woman. With the British School of Calderonistas, this attitude changed. A. E. Sloman explained how the main and secondary actions are linked.[26] Others like E. M. Wilson and William M. Whitby consider Rosaura to be central to the work since she parallels Segismundo's actions and also serves as Segismundo's guide, leading him to a final conversion.[27][28] For some Rosaura must be studied as part of a Platonic ascent on the part of the Prince. Others compare her first appearance, falling from a horse/hippogriff to the plot of Ariosto's Orlando furioso where Astolfo (the name of the character who deceives Rosaura in our play), also rides the hippogriff and witnesses a prophecy of the return of the mythical Golden Age. For Frederick de Armas, Rosaura hides a mythological mystery already utilized by Ariosto. When she goes to Court, she takes on the name of Astraea, the goddess of chastity and justice. Astraea was the last of the immortals to leave earth with the decline of the ages. Her return signals the return of a Golden Age. Many writers of the Renaissance and early modern periods used the figure of Astraea to praise the rulers of their times. It is possible that Rosaura (an anagram of auroras, "dawns") could represent the return of a Golden Age during the reign of Segismundo, a figure that represents King Philip IV of Spain.[29]

.jpg)

Segismundo's conclusions

There have been many different interpretations of the play’s ending, where Segismundo condemns the rebel soldier who freed him to life imprisonment in the tower. Some have suggested that this scene is ironic – that it raises questions about whether Segismundo will in fact be a just king. Others have pointed out that Calderón, who lived under the Spanish monarchy, could not have left the rebel soldier unpunished, because this would be an affront to royal authority.

It is worth considering that Segismundo’s transformation in the course of the play is not simply a moral awakening, but a realization of his social role as the heir to the throne, and this role requires him to act as kings act. For some, the act of punishing the rebel soldier makes him a Machiavellian prince.[30] Others argue that, while this action may seem unjust, it is in keeping with his new social status as the king. Daniel L. Heiple traces a long tradition of works where treason seems to be rewarded, but the traitor or rebel is subsequently punished.[31]

It may well be that, rather than intending his audience to see this action as purely right or wrong, Calderón purposefully made it ambiguous, creating an interesting tension in the play that adds to its depth.

Adaptations

Theatre

- A Dutch adaptation, Het Leven is maer Droom, was performed in Brussels in 1647, and printed by Jan Mommaert.

- Helen Edmundson's adaptation of Life Is a Dream was produced at the Donmar Warehouse in 2009, starring BAFTA Award-winner Dominic West.[32]

- Rosaura, a 2016 adaptation by Paula Rodríguez and Sandra Arpa which focuses on the principal female character in Calderon's play - showing how she fights against what life had done to her, as well as against the established order and the limits imposed on her[33][34][35][36]

- Calderón’s Two Dreams was presented by the Magis Theatre Company in February 2017 at La Mama Experimental Theatre Club, with a new translation of Life is a Dream 1635 play by George Drance SJ, and presented on the same bill with the autosacramental Life is a Dream translated by Drance and Alfredo Galván.

Opera

- Life Is a Dream by Jonathan Dove (composer) and Alasdair Middleton (libretist); Directed by Graham Vick. Premiered by Birmingham Opera Company, Argyle Works, Birmingham, on 21 March 2012;[37]

- Life Is a Dream by Lewis Spratlan (composer) and James Maraniss (librettist), premiered by the Santa Fe Opera on 24 July 2010.[38][39]

Other media

- Popular song: Some of the latter lines from Act 2 are sampled in the Jumpstyle song "Que es la Vida" by Martillo Vago.[40]

- Film: Raúl Ruiz's 1987 film Life is a dream is a partial adaptation of Life Is a Dream (and was distributed under this title in its English-language subtitled version).[41]

- Literature: Giannina Braschi's United States of Banana (2011) is a geopolitical tragicomedy about the liberation of Puerto Rico; the cross-genre work features a play in which Hamlet and Zarathustra seek to liberate Segismundo from the dungeon where he has been imprisoned by his father, King Basilio, for the crime of having been born.[42][43][44] The work was adapted to a comic book by Joakim Lindengren in 2017 by the same name.[45][46]

References

- Don W. Cruickshank, Don Pedro Calderon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009, p.78

- Brockett & Hildy, p.145

- Racz, Gregary (2006), Pedro Calderón de la Barca: Life Is a Dream, Penguin, p. viii, ISBN 978-0-14-310482-7

- "The 40 best plays to read before you die". The Independent. 18 August 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Cowans, Jon (ed). Early Modern Spain: A Documentary History, University of Pennsylvania Press (2003), p. 15

- Sara Constantakis, ed. (2006). Drama for students [Volume 23]: presenting analysis, context and criticism on commonly studied dramas (Collection). Detroit. ISBN 978-0-7876-8119-7.

- Kidd, Michael (2004). Critical Introduction to Pedro Calderon de la Barca's Life's a Dream. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 1–15.

- Payne, "Spanish Society and Economics in the Imperial Age" (Ch. 14)

- Kidd, Michael (2004). Critical Introduction to Pedro Calderon de la Barca's Life's a Dream. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 1–15.

- Kidd, Michael (2004). Critical Introduction to Pedro Calderon de la Barca's Life's a Dream. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 1–15. This religious fervor permeated the theatre of the time in that a prevalent theme was free will versus predestination.

- Suarez, Francisco (1971). DEFENSA DE LA FE (DEFENSIO FIDEI). Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Politicos de Madrid.

- Mariana, Jaun. On Kings and Kingship (1599)

- Brockett & Hildy, p. 134

- Payne, Stanley G. "The Spanish Empire" (Ch. 13) in A History of Spain and Portugal, vol. 1, The Library of Iberian Resources Online (1973), accessed December 7, 2013

- Constantakis, p.186

- Translation by Denis Florence Mac-Carthy in Calderon's Dramas, pp. 78–79. London: Henry S. King & Co., 1873

- De La Barca, Pedro Calderón. Introduction to "The Wonder-Working Magician" Archived 10 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, barca.classicauthors.net. Retrieved 8 November 2013

- Garcia Reidy, Alejandro. "Las posibilidades dramaticas de Barlaam y Josafat: De Lope de Vega a sus epigonos". Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- De Armas, Frederick A. "The Critical Tower", The Prince in the Tower: Perceptions of La vida es sueño, pp. 3–14, Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1993

- Osaura Parker, Alexander A. "The Father-Son Conflict in the Drama of Calderón", Forum for Modern language Studies, 2 (1966), pp. 99–113

- Ambrose, Timothy. "Calderón and Borges: Discovering Infinity in the Labyrinth of Reason", A Star-Crossed Golden Age: Myth and the Spanish Comedia, (ed.) Frederick A. de Armas, pp. 197–218. Lewisburg: Bucknell University press, 1998

- Maurin, Margaret S. "The Monster, the Sepulchre and the Dark: Related Patterns of Imagery in La vida es sueño", Hispanic Review, 35 (1967): 161–78

- Sullivan, Henry W. "The Oedipus Myth: Lacan and Dream Interpretation", The Prince in the Tower: Perceptions of La vida es sueño, pp. 111–117

- Heiple, Daniel L. "Life as Dream and the Philosophy of Disillusionment", The Prince in the Tower: Perceptions of La vida es sueño, pp. 118–131.

- Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, Calderón y su teatro. Madrid: A. Perez Dubrull, 1881.

- A. E. Sloman, "The Structure of Calderón's La vida es sueño," in Critical Essays on the Theater of Calderón," ed. Bruce W. Wardropper, 90–100. New York: New York University Press, 1965"

- E. M. Wilson, "On La vida es sueño," in Critical Essays on the Theater of Calderón, 63–89

- William Whitby "Rosarura's Role in the Structure of La vida es sueño," in Critical Essays on the Theater of Calderón, 101–13

- Frederick A. de Armas, The Return of Astraea: An Astral-Imperial Myth in Calderón. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1986.

- H. B. Hall, "Segismundo and the Rebel Soldier," Bulletin of Hispanic Studies 45 (1968): 189–200.

- Daniel L. Heiple, "The Tradition Behind the Punishment of the Rebel Soldier in La vida es sueño," Bulletin of Hispanic Studies 50 (1973): 1–17.

- https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2009/oct/15/life-is-a-dream-theatre-review

- "Rosaura - Corral de Comedias". Corraldealcala.com. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Review of Rosaura by Paula Rodriguez and Sandra Arpa". 15 July 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Billington, Michael (5 July 2016). "Rosaura review – feminists unlock the mystery of Calderón's classic". Theguardian.com. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "paula-rodriguez - ROSAURA". Paula-rodriguezact.com. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Birmingham Opera Company - Home". Birmingham Opera Company. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- David Belcher, "What Dreams May Come", Opera News, July 2010, Vol. 75, No. 1

- Que es la Vida – Martillo Vago, YouTube

- "Life Is a Dream (1987)". Retrieved 23 February 2019 – via www.imdb.com.

- "Hamlet and Segismundo," Minority Theatre on the Global Stage: Challenging Paradigms from the Margins. Gonzalez, Madelena., Laplace-Claverie, Hélène. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 2012. pp. 255–265. ISBN 1-4438-3837-3. OCLC 823577630.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Riofrio, John (1 March 2020). "Falling for debt: Giannina Braschi, the Latinx avant-garde, and financial terrorism in the United States of Banana". Latino Studies. 18 (1): 66–81. doi:10.1057/s41276-019-00239-2. ISSN 1476-3443.

- Cruz-Malavé, Arnaldo (1 September 2014). ""Under the Skirt of Liberty": Giannina Braschi Rewrites Empire". American Quarterly. 66: 801–818. doi:10.1353/aq.2014.0042.

- "Vol. 2, No. 2, Spring 2018 of Chiricú Journal: Latina/o Literatures, Arts, and Cultures on JSTOR". doi:10.2979/chiricu.2.issue-2. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Aldama, Frederick Luis. "Poets, Philosophers, Lovers: On the Writings of Giannina Braschi". upittpress.org. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

External links

| Spanish Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- New production of La vida es sueño in Spanish at Repertorio Español in New York City. November 2008

- Full text at Project Gutenberg in an English translation (Denis Florence MacCarthy, 1873)

- Theater project produced by Puy Navarro in collaboration with Amnesty International. Francisco Reyes, Associate Producer. March 2007 at The Culture Project, NYC

- Odeon Theatre, Bucharest, Romania. Life is Dream. 2011