Scots Mining Company House

The Scots Mining Company House, also known as Woodlands Hall, is an early-18th-century mansion house in Leadhills, South Lanarkshire, Scotland. The house was built around 1736 for the manager of the Leadhills mines, which were owned by the Earl of Hopetoun. Its design has been attributed to the architect William Adam.

| Scots Mining Company House | |

|---|---|

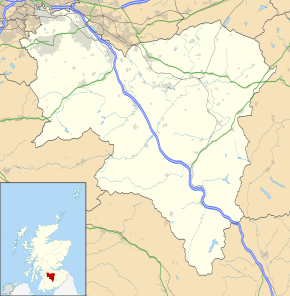

Location in South Lanarkshire | |

| Coordinates | 55.4145°N 3.761°W |

Listed Building – Category A | |

| Designated | 12 January 1971 |

| Reference no. | LB732 |

| Designated | 31 March 2006 |

| Reference no. | GDL00339 |

The house is now a category A listed building.[1] The garden, which is largely unchanged since it was laid out in the 18th century, is included on the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes in Scotland, the national listing of significant gardens.[2]

History

Lead and silver have been mined at Leadhills in the Southern Uplands for centuries. In the 17th century, Sir James Hope (1614–1661) married Anne, daughter of Robert Foulis of Leadhills, and the mines subsequently passed to his descendants the Earls of Hopetoun.[2] The Scots Mining Company, formally The Governor and Company for Working the Mines and Minerals in that part of North Britain called Scotland, was formed by a London-based group of Scottish merchants. They took a lease on part of the mines in 1729, and in 1735 they appointed James Stirling of Keir (1692–1770) as managing agent. Stirling was a noted mathematician and scientist who had lived in Venice and London, and was a member of the Royal Society.[3]

The house at Leadhills was built between 1734 and 1736 for James Stirling. At this time, the architect William Adam (1689–1748) was engaged by Charles Hope, 1st Earl of Hopetoun (1681–1742) at Hopetoun House, and Adam's name has been linked to the design of both the house and its garden, though the only record of his involvement is on a building account for the supply of timber.[1]

James Stirling proved adept at managing the Leadhills mines, despite his lack of practical experience. Under his tenure the mines became "one of the most profitable industrial enterprises in Scotland".[2] His paternalistic concern for worker's welfare was also noted, and had a long-lasting effect on the culture of the Leadhills mines.[3] In 1770 James' nephew Archibald Stirling succeeded his uncle as manager at Leadhills.[4]

By the middle of the 19th century, the lead mines were becoming less profitable, and a series of lawsuits affected the company's profitability. In 1861 the Scots Mining Company was wound up.[5] The manager's house became a shooting lodge, and a small chapel was built in the garden.[2] The gardens are now held by the Scots Mining Company House Trust, a registered charity. The trust seeks to maintain the gardens as a community resource, and aims to restore the herb garden.[4]

House and garden

The house comprises a two-storey main block with a piend roof. To this was added in 1737 a wing to the south, and in 1740 a larger wing to the north.[1] The gardens contain the remains of an ice house and a small chapel. The garden is surrounded by mature trees, the only woodland in the village. At the high point of the garden was a viewing platform overlooking the village, taken down in 2003.[2] A single storey entrance lodge has been demolished, and the former stables are now derelict and listed on the Buildings at Risk Register for Scotland.[6]

References

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Scots Mining Company House... (Category A) (LB732)". Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Scot's Mining Company House (GDL00339)". Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Harvey, W.S. "Chapter 2 Early Days". Lead and Labour: The story of the miners of Leadhills and Wanlockhead. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- "Scots Mining Company House". Leadhills website. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- Harvey, W.S. "Chapter 10 The Water Dispute". Lead and Labour: The story of the miners of Leadhills and Wanlockhead. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- "Stable Block". Buildings at Risk Register for Scotland. Scottish Civic Trust. Retrieved 16 March 2012.