Scotoplanes

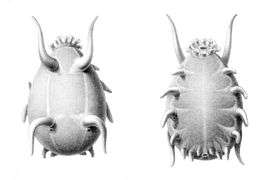

Scotoplanes, commonly known as the sea pig, is a genus of deep-sea sea cucumbers of the family Elpidiidae, order Elasipodida.

| Scotoplanes | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scotoplanes globosa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Scotoplanes |

| Species | |

| |

Locomotion

Members of the Elpidiidae have particularly enlarged tube "feet" that have taken on a leg-like appearance, using water cavities within the skin to inflate and deflate the appendages to move.[2] The "horns" on its back are also actually legs. Scotoplanes modify surficial elements in the ocean by moving through the sediment like a bulldozer. While the Scotoplanes move through the sediment, they disrupt the surface and the resident infauna as it feeds.[3]

Ecology

Scotoplanes live on deep ocean bottoms, specifically on the abyssal plain in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, typically at depths of over 1,200[4]–5,000 metres.[5] Some related species can be found in the Antarctic. Scotoplanes (and all deep-sea holothurians) are deposit feeders, and obtain food by extracting organic particles from deep-sea mud. Scotoplanes globosa has been observed to demonstrate strong preferences for rich, organic food that has freshly fallen from the ocean's surface,[6] and uses olfaction to locate preferred food sources such as whale corpses.[7] Scotoplanes have very fragile bodies; if they get caught in a trawler they break apart like jell-o. Scotoplanes, like many sea cucumbers, often occur in huge densities, sometimes numbering in the hundreds when observed. Early collections have recorded groups of up to 300-600 individuals. Sea pigs are also known to host different parasitic invertebrates, including gastropods (snails) and small tanaid crustaceans.

Scotoplanes sp, like other sea cucumbers, host parasitic and commensal organisms. For example, it provides a shelter to juvenile crabs, Neolithodes diomedeae. It is known that such relationship benefits the crabs because they can reduce risks of predation when they are under the shelter.[8]

Size

Scotoplanes can be as big as up to 4-6" (15 cm) long.[9]

Taxonomy

The genus includes the following species:[10]

.jpeg)

- Scotoplanes angelicus

- Scotoplanes globosa

- Scotoplanes mutabilis

References

- Théel, H (1886). "Report on the Holothurioidea dredged by HMS Challenger during the years 1873-76". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hansen, B. (1972). "Photographic evidence of a unique type of walking in deep-sea holothurians". Deep-Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts. 19 (6): 461–462. Bibcode:1972DSROA..19..461H. doi:10.1016/0011-7471(72)90056-3.

- Blake, James A.; Maciolek, Nancy J.; Ota, Allan Y.; Williams, Isabelle P. (2009-09-01). "Long-term benthic infaunal monitoring at a deep-ocean dredged material disposal site off Northern California". Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 56 (19–20): 1775–1803. Bibcode:2009DSRII..56.1775B. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.05.021.

- Barry, James P.; Taylor, Josi R.; Kuhnz, Linda A.; De Vogelaere, Andrew P. (2016-10-01). "Symbiosis between the holothurian Scotoplanes sp. A and the lithodid crab Neolithodes diomedeae on a featureless bathyal sediment plain". Marine Ecology. 38 (2): n/a. doi:10.1111/maec.12396. ISSN 1439-0485.

- Llano, George Biology of the Antarctic Seas III, Volume 11 of Antarctic research series, Volume 3 of Biology of the Antarctic seas, Issue 1579 of Publication (National Research Council (U.S.))) American Geophysical Union, 1967, p. 57

- Miller, R. J.; Smith, C. R.; Demaster, D. J.; Fornes, W. L. (2000). "Feeding selectivity and rapid particle processing by deep-sea megafaunal deposit feeders: A 234Th tracer approach". Journal of Marine Research. 58 (4): 653. doi:10.1357/002224000321511061.

- Pawson, DL; Vance, DJ (2005). "Rynkatorpa felderi, new species, from a bathyal hydrocarbon seep in the northern Gulf of Mexico (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea: Apodida)". Zootaxa. 1050: 15–20. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1050.1.2.

- Barry, James P.; Taylor, Josi R.; Kuhnz, Linda A.; De Vogelaere, Andrew P. (2017). "Symbiosis between the holothurian Scotoplanes sp. A and the lithodid crab Neolithodes diomedeae on a featureless bathyal sediment plain". Marine Ecology. 38 (2): e12396. Bibcode:2017MarEc..38E2396B. doi:10.1111/maec.12396.

- Bates, Mary (2014-06-16). "The Creature Feature: 10 Fun Facts About Sea Pigs". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- MarineSpecies.org – Scotoplanes

External links

- Scotoplanes article and photos on Echinoblog

- Sea pigs? Gross or cool? on Animal Planet website

- Sea Cucumbers: Holothuroidea – Sea Pig (scotoplanes Globosa): Species Accounts at Animal Life Resource

- Neptune Canada "Sea Pig Slow Dance"

- Scotoplanes as a refuge for crabs

Further reading

Ruhl, Henry A., and Kenneth L. Smith, Jr. "Go to Science." Science Magazine: Sign In. Science., 23 July 2004. Web. 1 May 2015. [1]

- Ruhl, Henry A.; Smith, Kenneth L. Jr. (23 July 2004). "Shifts in Deep-Sea Community Structure Linked to Climate and Food Supply". Science. 305 (5683): 513–515. Bibcode:2004Sci...305..513R. doi:10.1126/science.1099759. PMID 15273392.