Shewa

Shewa (Oromo: Shawaa; Amharic: ሸዋ), formerly romanized as Shua, Shoa, Showa, Shuwa (Scioà in Italian[1]), is a historical region of Ethiopia, formerly an autonomous kingdom within the Ethiopian Empire. The modern Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa is located at its center.

.svg.png)

The nucleus of Shewa is part of the mountainous plateau in what is currently the central area of Ethiopia, but prior to the Zemene Mesafint and after the loss of Bale with the invasion of Ahmed Al-Ghazi, Shewa was part of Ethiopia's southeasternmost frontier. Shewa was as defensible as any highland, and its government traced an administrative continuity with this earlier period despite the loss of neighboring lands to the Ethiopian Empire. At times, it was a haven; at other times, it was isolated from the rest of Ethiopia by hostile peoples.

The towns of Debre Berhan, Antsokia, Ankober, Entoto and, after Shewa became a province of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa have all served as the capital of Shewa at various times. Most of northern Shewa, made up of the districts of Menz, Tegulet, Yifat, Menjar and Bulga, is populated mostly by Christian Amharas , while southern is inhabited by the Gurages and eastern Shewa have large Oromo and Argobba Muslim populations. The monastery of Debre Libanos, founded by Saint Tekle Haymanot, is located in the district of Selale, also known in Amharic as Grarya, a former province of Abyssinia.[2]

History

Eastern Shewa first appears in the historical record as a Muslim state, which G. W. B. Huntingford believed was founded in 896, and had its capital at Walalah.[3] It is believed to have been part of the Kingdom of Aksum for over a millennium that became the site of Muslim kingdoms.[4] This state was absorbed by the Sultanate of Ifat around 1285. Recently, three urban centers thought to be part of the Muslim kingdom of Eastern Shewa were discovered by a group of French archaeologists.

Yekuno Amlak based his uprising against the Zagwe dynasty from an enclave in Shewa that was settled by Amhara Christians. He claimed Solomonic forebears, direct descendants of the pre-Zagwe Axumite emperors, who had used Shewa as their safe haven when their survival was threatened by Gudit and other enemies. This is the reason why the region got the name "Shewa" which means 'rescue' or 'save'. This claim is supported by the Kebra Nagast, a book written under one of the descendants of Yekuno Amlak, which mentions Shewa as part of the realm of Menelik I. Aksum and its predecessor Dʿmt were mostly limited to Northern Ethiopia and Eritrea during the 1st millennium BCE. However, Shewa eventually became a part of the Amhara-Abyssinian empire upon the rise of the Amhara Solomonic dynasty (following the Zagwe dynasty) as well as the Adal empire.[5]

In the 16th century, Shewa, which was still an Islamic moiety, and the rest of Christian Abyssinia were conquered by the forces of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi of the Adal Sultanate, and Shewa came under Muslim Adal rule. The region then came under pressure from the Oromo expansion, who succeeded during the first decades of the next century in settling the areas around Shewa (which were renamed Welega, Arsi and Wollo). Presently, the Oromos of Wollo and Arsi in particular are predominantly Muslim. Little is known about the details of the history of Shewa until almost 1800; however, Emperor Lebna Dengel and some of his sons used Shewa as their safe haven when threatened by invaders.

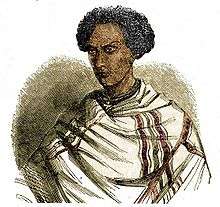

The Amhara Shewan ruling family was founded in the late 17th century by Negasi Krestos, who consolidated his control around Yifat. Traditions recorded about his ancestry vary: one tradition, recorded in 1840, claims his mother was the daughter of Ras Faris, a follower of Emperor Susenyos I who had escaped into Menz; another tradition told by Serta Wold, a councilor of Sahle Selassie, was that Negassie was a male-line descendant of Yaqob, the youngest son of Lebna Dengel, and thus assert descent from the ancient ruling Solomonic dynasty.[6] Thus the ruling family of Shewa were considered the junior branch of the Solomonic dynasty after the senior Gondar branch.

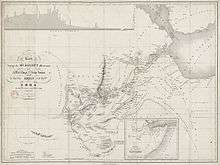

Negassie's son, Sebestyanos assumed the title of Meridazmach ("Fearsome Commander"), which was unique to Shewa. His descendants continued to bear this title until Sahle Selassie of Shewa was declared king of Shewa in the 1830s. The area was explored, as part of an effort to travel across Africa from east to west, by French explorer Rochet d'Héricourt during his expedition of 1842–1844. King Selassie welcomed d'Héricourt, and accompanied him with a group of his own entourage of Gallas tribesmen across his kingdom. D'Héricourt won the Grande Médaille d'Or des Explorations in 1847 for his detailed records of that journey, including his map identifying the area of the Rouyam de Choa (Kingdom of the Chao).

King Selassie's grandson, Sahle Maryam, eventually would succeed as Emperor of all Ethiopia at the end of the century under name Menelik II. The title of "King of Shewa" was subsumed into the imperial title of "Emperor of Ethiopia" when Menelik became Emperor.

Shewan kings spread their control towards the south and east, through lowland and desert, and succeeded in invading and subjecting some regions under their rule. The emperors of Ethiopia had long claimed these southern regions, and various direct and tributary relations had existed prior to the invasion of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi even though these regions such as the Hadiya kingdom and Bale kingdom were independent entities. The Oromo migrations following the Imam's defeat had cut off these old relationships and had drastically changed the demographics of the area by rolling back the Amhara expansion and migration, and creating new relationships. The kingdom of Shewa that Menelik II brought into the Ethiopian realm had been somewhat expanded, and thus added significantly to the total area of the empire. The northern migration of Oromos into Shewa since the 1500s changed its demography and strengthened Shewa's position against its rival Gondar in the empire. Having already influenced Gondar in the 1700s, Oromos in Shewa gained power in the 1800s, particularly the Tulama. Ras Gobana was notable for forming alliances and militarily extending Shoan domain to the south.

Ethiopia reached further frontiers through expansion to the east and south, resulting in the Shewan region as the physical center of the modern country.

In recent times, Shewa was a Governorate-General (province) under the monarchy, and was then an Administrative Region of Ethiopia under the Derg military regime until 1987. In that year, upon the proclamation of the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia under the now civilianized Derg, Shewa was split into four Administrative Regions: North Shewa, Southern Shewa, Eastern Shewa and Western Shewa. Following the fall of the Derg in 1991, the old historic provinces and regions were abolished, replaced with the present ethnic-based Regions of Ethiopia (based on ethnic and linguistic boundaries). The former province of Shewa territory as it was before 1995 was split between the Amhara Region, Oromia Region, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region, and Afar Region, with larger parts annexed by the former two, as well as the Addis Ababa autonomous area.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 991.

- http://www.niras.com/business-areas/~/media/files/niras-com/development-consulting/nic-ethiopia-october-2011.ashx. Retrieved 10 April 2014. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - G. W. B. Huntingford, The historical geography of Ethiopia from the first century AD to 1704, (Oxford University Press: 1989), p. 76

- ancient shewa in ethiopia

- Aksum/Abyssinia vis a vis Adal

- Mordechai Abir, Ethiopia: the Era of the Princes (London: Longmans, 1968), pp. 144ff.

.svg.png)