Science and technology in Turkmenistan

Science and technology in Turkmenistan examines government policies relative to the promotion of science, technology and innovation in Turkmenistan.

Socio-economic context

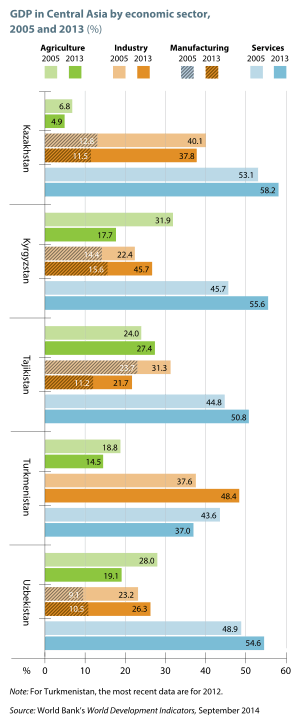

Turkmenistan has been undergoing rapid change − with little social upheaval − since the election of President Gurbanguly Berdimuhammadov in 2007 (re-elected in 2012), following the death of ‘president for life’ Sparamurat Niyazov. Turkmenistan has been moving towards a market economy ever since this policy was enshrined in the Constitution in 2008. In parallel, however, the government offers a minimum wage and continues to subsidize a wide range of commodities and services, including gas and electricity, water, wastewater disposal, telephone subscriptions, public transportation (bus, rail and local flights) and some building materials (bricks, cement, slate).[1]

Economic liberalization policies are being implemented gradually. Thus, as the standard of living has risen, some subsidies have been removed, such as those for flour and bread in 2012. Turkmenistan has one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. By introducing a fixed exchange rate of US$1 to 2.85 Turkmen manat in 2009, the president caused the ‘black’ foreign exchange market to disappear, making the economy more attractive to foreign investment.[1]

A fledgling private sector is emerging with the opening of the country's first iron and steel works and the development of a chemical industry and other light industries in construction, agro-food and petroleum products. Turkmen gas is now exported to China and the country is developing one of the largest gas fields in the world, Galkinish, with estimated reserves of 26 trillion m3 of gas. Avaz on the Caspian Sea has been turned into a holiday resort, with the construction of dozens of hotels which can accommodate more than 7 000 tourists. In 2014, some 30 hotels and holiday homes were under construction.[1]

The country has embarked on a veritable building boom, with the construction of 48 kindergartens, 36 secondary schools, 25 sports academies, 16 stadiums, 17 health centres, 8 hospitals, 7 cultural centres and 1.6 million m2 of housing in 2012 alone. Across the country, roads, shopping centres and industrial enterprises are all under construction. Turkmenistan's railway transport and metropolitan trains have been upgraded and the country is buying state-of-the-art aircraft.

Schools around the country were being renovated in 2014, with 20-year old textbooks being replaced and modern multimedia teaching methods introduced. All schools, universities and research institutes are being equipped with computers, broadband and digital libraries. Internet has only been available to the public since 2007, which explains why just 9.6% of the population had access to it in 2013, the lowest proportion in Central Asia.[1]

Movement within the country has become easier with the removal of identity checkpoints – at one time there were no fewer than 10 between Ashgabat and Turkmenabat. This development should facilitate the mobility of scientists around the country.[1]

Research priorities

Twelve priority areas

President Berdimuhammadov is far more committed to science than his predecessor. In 2009, he restored the Turkmen Academy of Sciences and its reputed Sun Institute, both dating from the Soviet era. The exploration of the potential use of solar energy and other renewable sources of energy is one of the 12 priority research areas determined by the president in 2010. The full list is as follows:[1]

- Extraction and refining of oil and gas and mining of other minerals;

- Development of the electric power industry, with exploration of the potential use of alternative sources of energy: sun, wind, geothermal and biogas;

- Seismology;

- Transportation;

- The development of Information and communication technologies;

- Automation of production;

- Conservation of the environment and, accordingly, introduction of non-polluting technologies that do not produce waste;

- Development of breeding techniques in the agricultural sector;

- Medicine and pharmaceuticals;

- Natural sciences; and

- Humanities, including the study of the country's history, culture and folklore.

Sun Institute

The Sun Institute was restored by the president in 2009 and has since been renamed the Institute of Solar Energy. Although Turkmenistan is blessed with abundant oil and gas reserves and produces enough electric power for its own needs, it is difficult to lay power lines in the Kopet Dag mountains or arid parts of the country: about 86% of Turkmenistan is desert. Local generation of wind and solar energy gets around this problem and creates jobs.[1]

Scientists at the Sun Institute are implementing a number of long-term projects, such as the design of minisolar accumulators, solar batteries, wind and solar photovoltaic plants and autonomous industrial mini-biodiesel units. These units will be used to develop arid areas and the territory around the Turkmen Lake, as well as to foster tourism in Avaz on the Caspian seashore. In isolated parts of the country, ‘sun’ scientists are working on schemes to pump water from wells and boreholes, recycle household and industrial wastes, produce biodiesel and organic fertilizers and raise ‘waste-free’ cattle. Their achievements include solar drying and desalination units, the cultivation of algae in solar photobioreactors, a ‘solar’ furnace for high temperature tests, solar greenhouses and a biogas production unit. A wind and energy unit has been installed on Gyzylsu Island in the Caspian Sea to supply water to the local school.[1]

Within the Tempus project, ‘sun’ scientists have been trained (or retrained) since 2009 at the Technical University Mountain Academy of Freiberg (Germany). ‘Sun’ scientists are also studying the possibility of producing silicon from the Karakum sands for photovoltaic converters, thanks to a grant from the Islamic Development Bank.[1]

Modernization of research infrastructure

Creation of research hubs

Many national research institutions established during the Soviet era have since become obsolete with the development of new technologies and changing national priorities. This has led Turkmenistan to reduce the number of its research institutions since 2009 by grouping existing ones to create research hubs. Several of the Turkmen Academy of Science's institutes were merged in 2014: the Institute of Botany was merged with the Institute of Medicinal Plants to become the Institute of Biology and Medicinal Plants; the Sun Institute was merged with the Institute of Physics and Mathematics to become the Institute of Solar Energy; and the Institute of Seismology merged with the State Service for Seismology to become the Institute of Seismology and Atmospheric Physics.[1]

Development of technology parks

Turkmenistan is developing technology parks as part of the drive to modernize infrastructure. In 2011, construction began of a technopark in the village of Bikrova near Ashgabat. It will combine research, education, industrial facilities, business incubators and exhibition centres. The technopark will house research on alternative energy sources (sun, wind) and the assimilation of nanotechnologies.[1]

A National Space Agency

In 2011, the president signed a decree creating the National Space Agency, which will be responsible for monitoring the Earth's orbit, launching satellite communication services, conducting space research and operating an artificial satellite over Turkmenistan's territory.[1]

A new university

The Turkmen State Institute of Oil and Gas was founded in 2012 before being transformed into the International Oil and Gas University a year later. Built on a 30-hectare site which includes a Centre for Information Technology, it can accommodate 3,000 students. This brings the number of training institutes and universities in the country to 16, including one private institution.[1]

Human resources

Career incentives

The government has introduced a series of measures to encourage young people to pursue a career in science or engineering. These include a monthly allowance throughout their degree course for students enrolled in science and engineering and a special fund targeting the research of young scientists in priority areas for the government, namely:[1]

- the introduction of innovative technologies in agriculture;

- ecology and the rational use of natural resources;

- energy and fuel savings;

- chemical technology and the creation of new competitive products;

- construction;

- architecture;

- seismology;

- medicine and drug production;

- information and communication technologies;

- economics; and

- the humanities.

It is hard to gauge the impact of government measures in favour of research, since Turkmenistan does not make data available on higher education, research expenditure or researchers.[1]

Gender issues

One of the first laws adopted under Berdimuhammadov's presidency offered a state guarantee of equality for women, in December 2007. Some 16% of parliamentarians are women but there are no data on women researchers. A group of women scientists have formed a club to encourage women to choose a career in science and increase the participation of women in state programmes for science and technology and in decision-making circles. In 2015, the chair was Edzhegul Hodzhamadova, Senior Researcher at the Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences. Club members meet with students, deliver lectures and give interviews to the media. The club is endorsed by the Women's Union of Turkmenistan, which has organized an annual meeting of more than 100 women scientists on National Science Day (12 June) ever since the day was instituted in 2009.[1]

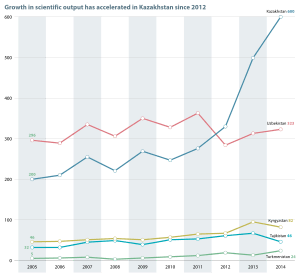

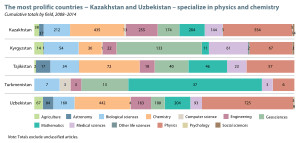

Trends in research output

The number of scientific papers published in Central Asia grew by almost 50% between 2005 and 2014, driven by Kazakhstan, which overtook Uzbekistan over this period to become the region's most prolific scientific publisher, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded). Turkmen scientists published most in the field of mathematics between 2008 and 2014. Scientific output rose between 2005 and 2014 from seven to 24 articles per year. This corresponds to five scientific articles per million inhabitants in 2014, the same ratio as for Tajikistan.

In comparison, Kazakh scientists tripled their output to 600 articles in a year between 2005 and 2014. They produced 35% of Central Asian articles recorded in the Thomson Reuters' database in 2005 and as many as 56% in 2014. Kazakh output nevertheless remains modest. There were 36 articles per million inhabitants in Kazakhstan in 2014, compared to 15 per million for Kyrgyzstan and 11 per million for Uzbekistan.[1]

The main partners of Turkmen scientists between 2008 and 2014 were Turkey (50 articles), the Russian Federation (11 articles), USA and Italy (6 each), China and Germany (4 each).[1]

No Turkmen patents were registered at the US Patent and Trademark Office between 2008 and 2013, compared to five for Kazakh inventors and three for Uzbek inventors. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan likewise registered no patents over this period.[1]

International co-operation

Turkmenistan is encouraging international co-operation with major scientific and educational centres abroad, including long-term partnerships. International scientific meetings have been held in Turkmenistan regularly since 2009 to foster joint research and the sharing of information and experience.[1]

Like the other four Central Asian republics, Turkmenistan is a member of several international bodies, including the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Economic Cooperation Organization and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. All five Central Asian republics are also members of the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Programme, which also includes Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, China, Mongolia and Pakistan. In November 2011, the 10 member countries adopted the CAREC 2020 Strategy, a blueprint for furthering regional co-operation. Over the decade to 2020, US$50 billion is being invested in priority projects in transport, trade and energy to improve members’ competitiveness. The landlocked Central Asian republics are conscious of the need to co-operate in order to maintain and develop their transport networks and energy, communication and irrigation systems. Only Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan border the Caspian Sea and none of the republics has direct access to an ocean, complicating the transportation of hydrocarbons, in particular, to world markets.[1]

Whereas Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan have been members of the World Trade Organization since 1998, 2013 and 2015 respectively, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have adopted a policy of self-reliance.[1]

Sources

![]()

References

- Mukhitdinova, Nasiba (2015). Central Asia. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 365–387. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.