Science and technology in Malawi

This article examines trends and developments in science and technology in Malawi.

Socio-economic context

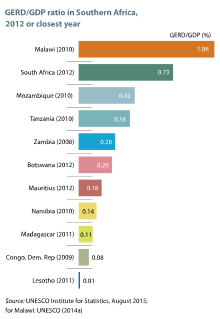

One of the poorest countries in the world, Malawi nevertheless spends 1% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on research and development (R&D), one of the highest ratios in Africa, even if R&D spending remains low in real terms. Malawi thus has the potential to harness science, technology and innovation to reducing poverty and diversifying its agriculture-dependent economy. The challenge will be to attract sufficient foreign direct investment (FDI) to foster technology transfer and empower the private sector to serve as an engine of economic growth.[1]

Having enjoyed stable democratic government for the past two decades, ever since the introduction of a multiparty system in 1994, the country is a potentially reassuring destination for foreign investors. The government has recently begun reforming its financial management system and has put a series of fiscal incentives in place to attract foreign investors. The country has also introduced a series of policy instruments to promote FDI, including tax incentives and the Malawi Innovation Challenge Fund for private businesses, which nurtures productive partnerships between leading firms and poor producers and entrepreneurs. The need for research and services is enormous, in a country where 93% of the population still lacks access to electricity, 47% improved sanitation and one in four adults lacks any form of family planning.[1]

Over the decade from 2003 to 2013, the economy grew annually by 5.6% on average, making it the sixth-fastest growing economy in the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Between 2009 and 2013, GDP per capita rose by 6%, from $713 to $755 in purchasing power parity.[2] It is projected that, between 2015 and 2019, annual growth in real GDP will range from 5% to 6%.[3] Malawi's ratio of donor funding to capital formation rose considerably over the period 2007–2012.[2] The African continent plans to create an African Economic Community by 2028, which would be built on the main regional economic communities, including the SADC.

Malawi has one of the lowest levels of human development in the SADC but is also one of three African countries that have been ‘making especially impressive progress for several Millennium Development Goals,’ along with Gambia and Rwanda, including with regard to primary school net enrolment (83% in 2009) and gender parity, which has been achieved at primary school level.[1]

Enrollment in higher education is struggling to keep up with rapid population growth. Despite a slight improvement, only 0.81% of the age cohort was enrolled in university by 2011. Moreover, although the number of students choosing to study abroad increased by 56% between 1999 and 2012, their proportion decreased from 26% to 18% over the same period. Malawi devoted 5.4% of GDP to education in 2011. Of this, 1.4% of GDP went to funding higher education. Between 2006 and 2012, the number of students enrolled in higher education almost doubled to 12,203.[2]

An economy dependent on agriculture

The economy of Malawi is predominantly agricultural. Over 80% of the population is engaged in subsistence farming, even though agriculture only contributes to 27% of GDP. The services sector accounts for more than half of GDP (54%), compared to 11% for manufacturing and 8% for other industries, including natural uranium mining.[2] Malawi invests more in agriculture (as a share of GDP) than any other African country: 28% of GDP.[4]

Agriculture accounts for 90% of export revenue. The three most important export crops are tobacco, tea and sugar cane – with the tobacco sector alone accounting for half of exports. Moreover, most products are exported in a raw or semi-processed state. Tobacco accounts for half of the country's exports (50%), natural uranium and its compounds for a further 10% and raw sugar cane for 8%.[2][1]

The government's attempts to diversify the agriculture sector and move up the global value chain have been seriously constrained by poor infrastructure, an inadequately trained work force and a weak business climate.[2]

National Export Strategy

In 2013, the government adopted a National Export Strategy to diversify the country's exports. Production facilities are to be established for a wide range of products within the three selected clusters: oil seed products, sugar cane products and manufacturing. The government estimates that these three clusters have the potential to represent more than 50% of Malawi's exports by 2027. In order to help companies adopt innovative practices and technologies, the strategy makes provision for greater access to the outcome of international research and better information about available technologies; it also helps companies to obtain grants to invest in such technologies from sources such as the country's Export Development Fund and the Malawi Innovation Challenge Fund.[2][1]

Fiscal incentives to attract foreign investors

Malawi is conscious of the need to attract more FDI to foster technology transfer, develop human capital and empower the private sector to drive economic growth. FDI has been growing since 2011, thanks to a government reform of the financial management system and the adoption of an Economic Recovery Plan. FDI in Malawi amounted to 3.2% of GDP in 2013. In 2012, the majority of investors came from China (46%) and the UK (46%), with most FDI inflows going to infrastructure (62%) and the energy sector (33%).

The government has introduced a series of fiscal incentives to attract foreign investors, including tax breaks. In 2013, the Malawi Investment and Trade Centre put together an investment portfolio spanning 20 companies in the country's six major economic growth sectors, namely:[2][1]

- Agriculture;

- manufacturing;

- energy (bio-energy, mobile electricity);

- tourism (ecolodges);

- infrastructure (wastewater services, fibre optic cables, etc.); and

- mining.

Malawi Innovation Challenge Fund

The Malawi Innovation Challenge Fund is a competitive facility, through which businesses in Malawi's agricultural and manufacturing sectors can apply for grant funding for innovative projects with potential for making a strong social impact and helping the country to diversify its narrow range of exports. The first round of competitive bidding opened in April 2014.[2][1]

The fund is aligned on the three clusters selected within the country's National Export Strategy: oil seed products, sugar cane products and manufacturing. It provides a matching grant of up to 50% to innovative business projects to help absorb some of the commercial risk in triggering innovation. This support should speed up the implementation of new business models and/or the adoption of technologies.[2][1]

The fund is endowed with US$8 million from the United Nations Development Programme and the UK Department for International Development.[2][1]

Investment in research and development

_in_Southern_Africa_per_million_inhabitants%2C_2013_or_closest_year.svg.png)

Despite being one of the poorest countries in the world, Malawi devoted 1.06% of GDP to GERD in 2010, according to a survey by the Department of Science and Technology, one of the highest ratios in Africa. This corresponds to $7.8 per researcher (in current purchasing parity dollars).[2][1]

In 2010, Malawi counted 123 researchers (in head counts) per million inhabitants, a median number for Southern Africa. This was a higher ratio than the average for sub-Saharan Africa as a whole: 91 researchers per million inhabitants. In Malawi, one in five researchers were women in 2010.[2]

Malawi is considered as having a viable national innovation system.

Status of national innovation systems in the Southern Africa Development Community in 2015, in terms of their potential to survive, grow and evolve

| Category | Country | Description |

| Fragile | Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Madagascar, Swaziland, Zimbabwe | Fragile systems tend to be characterized by political instability, be it from external threats or internal political schisms. |

| Viable | Angola, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, Tanzania, Zambia | Viable systems encompass thriving systems but also faltering ones, albeit in a context of political stability. |

| Evolving | Botswana, Mauritius, South Africa | In evolving systems, countries are mutating through the effects of policy and their mutation may also affect the emerging regional system of innovation. |

Source of table: Mbula-Kraemer, Erika and Scerri, Mario (2015) Southern Africa. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030. UNESCO, Paris, Table 20.5.

Scientific productivity

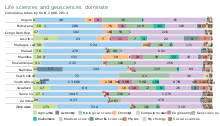

In 2014, Malawian scientists had the third-largest output in Southern Africa, in terms of articles catalogued in international journals. They published 322 articles in Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index expanded) that year, almost triple the number in 2005 (116). Only South Africa (9,309) and the United Republic of Tanzania (770) published more.

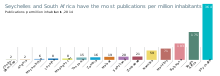

Malawian scientists publish more in mainstream journals – relative to GDP – than any other country of a similar population size. This is impressive, even if the country's publication density remains modest, with just 19 publications per million inhabitants catalogued in international journals in 2014, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index expanded). This compares with 6 for Mozambique, 15 for the United Republic of Tanzania, 20 for Swaziland, 21 for Zimbabwe, 59 for Namibia, 71 for Mauritius, 103 for Botswana (103) and 364 for South Africa.[2][1]

Between 2008 and 2014, scientists from Malawi collaborated most with their peers from the United States of America, followed by the UK, South Africa and ex aqueo Kenya and the Netherlands, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science.[2]

Science and technology policy

Science policy revision

Malawi's first science and technology policy from 1991 was revised in 2002. Despite being approved, the 2002 policy has not been fully implemented, largely due to the lack of an implementation plan and an unco-ordinated approach to STI. This policy has been under revision in recent years, with UNESCO assistance, to re-align its focus and approaches with the second Malawi Growth and Development Strategy (2013) and with international instruments to which Malawi is a party.[2][1]

The National Science and Technology Policy of 2002 envisaged the establishment of a National Commission for Science and Technology to advise the government and other stakeholders on science and technology-led development. Although the Science and Technology Act of 2003 made provision for the creation of this commission, it only became operational in 2011, with a secretariat resulting from the merger of the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Council. The Science and Technology Act of 2003 also established a Science and Technology Fund to finance research and studies through government grants and loans but, as of 2014, it was not yet operational.

The Secretariat of the National Commission for Science and Technology reviewed the Strategic Plan for Science, Technology and Innovation (2011–2015) but, as of early 2015, the revised policy had not yet met with Cabinet approval.[2][1]

Achievements stemming from policy implementation

Among the notable achievements stemming from the implementation of national policies for science, technology and innovation in recent years are the:[2][1]

- establishment, in 2012, of the Malawi University of Science and Technology and the Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (LUANAR) to build STI capacity. LUANAR was delinked from the University of Malawi. This brings the number of public universities to four, with the University of Malawi and Mzuzu University;

- improvement in biomedical research capacity through the five-year Health Research Capacity Strengthening Initiative (2008–2013) awarding research grants and competitive scholarships at PhD, master's and first degree levels, supported by the UK Wellcome Trust and DfID;

- strides made in conducting cotton confined field trials, with support from the US Program for Biosafety Systems,Monsanto and LUANAR.

- introduction of ethanol fuel as an alternative fuel to petrol and the adoption of ethanol technology;

- launch of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Policy for Malawi in December 2013, to drive the deployment of ICTs in all economic and productive sectors and improve ICT infrastructure in rural areas, especially via the establishment of telecentres; and

- a review of secondary school curricula in 2013.

Regional policy framework for science and technology

Malawi is not one of four SADC countries which had ratified the SADC Protocol on Science, Technology and Innovation (2008) by 2015. Ten of the 15 SADC countries must ratify the protocol for it to enter into force but, by 2015, only Botswana, Mauritius, Mozambique and South Africa had done so. The protocol promotes legal and political co-operation. It stresses the importance of science and technology for achieving 'sustainable and equitable socio-economic growth and poverty eradication'.[2]

Two primary policy documents operationalize the SADC Treaty (1992), the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan for 2005–2020, adopted in 2003, and the Strategic Indicative Plan for the Organ (2004). The Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan for 2005–2020 identifies the region's 12 priority areas for both sectorial and cross-cutting intervention, mapping out goals and setting up concrete targets for each. The four sectorial areas are: trade and economic liberalization, infrastructure, sustainable food security and human and social development. The eight cross-cutting areas are:[2]

- poverty;

- combating the HIV/AIDS pandemic;

- gender equality;

- science and technology;

- information and communication technologies (ICTs);

- environment and sustainable development;

- private sector development; and

- statistics.

Targets include:[2]

- ensuring that 50% of decision-making positions in the public sector are held by women by 2015;

- raising gross domestic expenditure on research and development (GERD) to at least 1% of GDP by 2015;

- increasing intra-regional trade to at least 35% of total SADC trade by 2008 (10% in 2008);

- increasing the share of manufacturing to 25% of GDP by 2015; and

- achieving100% connectivity to the regional power grid for all member states by 2012.

A 2013 mid-term review of the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan for 2005–2020 noted that limited progress had been made towards STI targets, owing to the lack of human and financial resources at the SADC Secretariat to co-ordinate STI programmes. Meeting in Maputo, Mozambique, in June 2014, SADC ministers of science, technology and innovation, education and training adopted the SADC Regional Strategic Plan on Science, Technology and Innovation for 2015–2020 to guide implementation of regional programmes.[2]

Concerning sustainable development, in 1999, the SADC adopted a protocol governing wildlife, forestry, shared water courses and the environment, including climate change, the SADC Protocol on Wildlife Conservation and Law Enforcement (1999). More recently, SADC has initiated a number of regional and national initiatives to mitigate the impact of climate change. In 2013, ministers responsible for the environment and natural resources approved the development of the SADC Regional Climate Change programme. In addition, COMESA, the East African Community and SADC have been implementing a joint five-year initiative since 2010 known as the Tripartite Programme on Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation, or The African Solution to Address Climate Change.[2]

See also

Science and technology in Botswana

Science and technology in Tanzania

Sources

![]()

References

- Lemarchand, Guillermo A.; Schneegans, Susan (eds) (2014). Mapping Research and Innovation in the Republic of Malawi (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100032-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kraemer-Mbula, Erika; Scerri, Mario (2015). Southern Africa. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 535–555. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- African Economic Outlook. African Development Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations Development Programme. 2014.

- The Maputo Commitments and the 2014 African Year of Agriculture (PDF). ONE.org. 2013.