Science & Vie

Science & Vie (French pronunciation: [sjɑ̃seˈvi]; French for Science and Life) is a monthly science magazine published in France. Its headquarters is in Paris.[1]

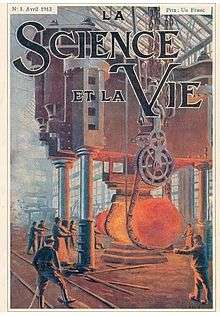

April 1913 cover | |

| Categories | Science magazine |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Monthly |

| Year founded | 1913 |

| Company | Mondadori France |

| Country | France |

| Based in | Paris |

| Language | French |

History and profile

The magazine was started in 1913 with the name La Science et la Vie.[1] In 1982, a spinoff computer magazine, Science & Vie Micro (SVM) was launched. The first magazine was published at the end of 1983 and was such a success that the number of copies were insufficient on the market. Another spinoff for teenagers, Science & Vie Junior was started in 1986. It was first published by Excelsior Publications until the latter was bought by Emap Plc in 2003. In June 2006 the magazine became part of Mondadori France.[2]

Science & Vie was divided in three sections, Science (Sciences), Technologie (Technology), Vie Pratique (Daily life). While the Science section reported on recent scientific progress, the Technology section would report on recent technical advances. Science & Vie covered technical advances in industry, but also in military technology. In particular, it featured articles on explosives, firearms, chemical weapons and nuclear weapons. The Vie Pratique section was concerned with technology in daily life. It included articles on photography, personal computers, video recording equipment or television. Besides these three sections, Science & Vie contained a section on amateur electronics by Henri-Pierre Penel, a section on amateur astronomy La Calculette de l'Astronome, and two sections on computer programming in BASIC, one on video games (first for the Sinclair ZX 81, and then the ZX Spectrum) and another of elementary numerical analysis, Le Micro de l'Ingénieur (with listings for the Apple II). This made Science & Vie a more popular magazine (both in terms of circulation and in terms of the level of education of its readers) than La Recherche or Pour la Science which are only concerned with science, or Industries & Techniques which only deals with applications of technology in industry.

Another important distinctive feature of Science & Vie was its willingness to tackle the issue of pseudoscience. The magazine was very critical of astrology, homeopathy, and pseudoscience. With the help of magician Gérard Majax, it has exposed the tricks used by Uri Geller to bend spoons and make small objects fly.[3] In 1989, it strongly criticized the claims of Jacques Benveniste of having observed water memory.[4] The magazine also uncovered the fabrication of the autopsy of an alien body supposedly discovered in Roswell, New Mexico.[5] The magazine was also very supportive of Henri Broch's debunking of paranormal claims. In general, articles on paranormal topics were marked as Blurgs, an acronym for Balivernes lamentables à l'usage réservé des gogos ("deplorable nonsense reserved for use by the gullible"). Since being bought by Mondadori, the magazine has adopted a less skeptical line.

In 2004 Science & Vie sold 361,273 copies.[6] In 2010 the circulation of the magazine was 281,000 copies.[7]

References

- Europa World Year. Taylor & Francis Group. 2004. p. 1699. ISBN 978-1-85743-254-1. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "A new Mondadori" (PDF). Borsa Italiana. 21 June 2006. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- Parapsychologie : des charlatans déguisés en savants Science&Vie n° 774 march 1982, p. 74

- La mémoire de l'eau Science&Vie n° 856 january 1989 p. 22

- Extraterrestres: la grande arnaque (affaire Roswell) Science&Vie n°935 August 1995 page 88

- E. Martin (30 November 2005). Marketing Identities Through Language: English and Global Imagery in French Advertising. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-230-51190-3. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- "Western Europe Media Facts. 2011 Edition" (PDF). ZenithOptimedia. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

External links

- Science & Vie website (in French)

- Science & Vie Micro website (in French)

- Science & Vie Junior website (in French)

- Index of past issues of Science & Vie (in French)

- Index of past issues of Science & Vie Micro (in French)