Schlierbach Abbey

Schlierbach Abbey (German: Stift Schlierbach) is a Cistercian monastery in Schlierbach, Austria founded in 1355, and rebuilt in the last quarter of the 17th century. The original foundation was a convent for nuns, abandoned around 1556 during the Protestant Reformation. The abbey was reoccupied as a monastery in 1620, and rebuilt in magnificent baroque style between 1672 and 1712. The monastery again went into decline with the upheavals before, during and after the Napoleonic era. It recovered only towards the end of the 19th century. In the 20th century the abbey established a viable economy based on a glass works, school, cheese manufacturing and other enterprises. The abbey is open to visitors, who may take tours, attend workshops and dine at the monastery restaurant.

The abbey, April 2014 | |

Location within Austria | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Cistercians |

| Established | 22 February 1355 |

| People | |

| Architecture | |

| Architect | Pietro Francesco Carlone |

| Style | Baroque |

| Site | |

| Coordinates | 47°56′10″N 14°07′37″E |

History

Convent

The convent of Aula Beatae Virginis (Hall of the Blessed Virgin) was established in 1355 by Eberhard von Wallsee, governor of Upper Austria, in a castle that he owned.[1] The abbey became the home of Cistercian nuns, who took up residence on 22 February 1355.[2] Schlierbach was also called Marien Saal (Our Lady's Seal). A 1762 description noted that it was "situate on an eminence, which gives it the agreeable prospect of the beautiful Kremsthal. This cloyster was erected in the year 1355, and is possessed of the citadels of Mossenbach, Hochhaus near Forchdorf, and Grub or Muhlgrub."[3] The Schöne Madonna sculpture held by the abbey was made for Albrecht II (the Lame) around 1340 and donated to the nuns.[4]

During the Protestant Reformation the convent closed down around 1556 and was neglected for 64 years.[2] In the 1570s the abandoned convent's properties were being profitably administered by the governor of Upper Austria, Dietmar, Lord of Losenstein.[5] From about 1594 to about 1600 Johann Stainsdorfer of the Schotten Abbey was the administrator, and then the Kremsmünster Abbey took over administration.[6]

Monastery

In 1620 the convent was given to the male branch of the Cistercians.[7] Monks from the Rein Abbey near Graz moved into the abbey. The monastery has been occupied since then.[2] The third abbot, Balthasar Rauch, was invested in 1643. Between 1672 and 1712, particularly under abbots Benedikt Rieger (1679–95) and Nivard Dierer (1696–1715) the abbey was magnificently rebuilt and expanded.[1] The work was undertaken by members of the Carlone family, and these buildings remain today.[2] The plans for the abbey's new church were supplied by Pietro Francesco Carlone, and the work was executed by his sons.[8] Starting in 1770 Valentin Hochleitner of Spital am Pyhrn built the organ in the monastery church.[1]

The library collection dates from the start of the 18th century, when the current library building was erected. In a sermon in 1735 the abbot Christian Stadler (r. 1715-1740) complained that the books his predecessor abbot Nivard II Dierer (r. 1695-1715) had purchased at great cost were still not organized. Melchior Zobl (c. 1697-1767) was appointed librarian and tasked with cataloging the books. Several important collections were added to the library, and by the end of the 18th century the building was too small. At this time the separate Frater library was established for theological reference works. There were various upheavals over the years, with some books placed in storage and later lost, before the Abbey library was restored in 1974-75 and the collection again organized.[6]

The abbey went into decline when Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (1765–1790) implemented his enlightened reforms, known as Josephinism. In 1809 choral prayers were temporarily suspended. There were other problems, from which the monastery only recovered only in the second half of the 19th century. Abbot Alois Wiesinger (r. 1917-55) expanded the economic basis of the monastery. The stained glass workshop gained a worldwide reputation. He also founded a school.[1] The abbey's glass shop made the stained glass windows for the Chapel of the Resurrection, Brussels, which was built in 1907. The windows, which depict five biblical topics, were painted by Thomas Reinhold of Vienna.[9] The monastery has run a school since 1925. It became active in mission work in 1938 when in founded the Jequitibá mission abbey in Bahia, Brazil.[10]

Today

As of 2008 there were 25 members of the monastery. The Cistercians follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, with its motto of Ora et Labora (pray and work).[10] The monastery today makes cheeses, cider, wine, beer and glass objects. It is open to visitors, and features the Genusszentrum (Pleasure center) restaurant, store and gallery. Visitors can take tours and workshops to learn about the process of cheese making and glass work.[11] St. Severin cheese is one of those made at the abbey. The recipe was brought to the abbey in 1920 by Friar Leonhard. It takes its name from Saint Severinus of Noricum, the protector against starvation.[12]

The monks assist in pastoral work among about 18,000 Catholics in nine neighboring parishes: Heiligenkreuz, Kirchdorf an der Krems, Klaus an der Pyhrnbahn, Micheldorf, Nußbach, Schlierbach, Steinbach am Ziehberg, Steyrling and Wartberg an der Krems.[10]

Gallery

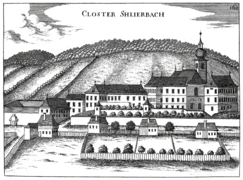

The abbey c. 1674 by Georg Matthäus Vischer

The abbey c. 1674 by Georg Matthäus Vischer Abbey towers

Abbey towers- Abbey garden

- Inner Yard

- Cloistered courtyard

- Nave of the abbey church

- Organ of the abbey church

- Baroque interior of the church

Ceiling fresco in Bernardisaal (detail): Apollo and the nine muses

Ceiling fresco in Bernardisaal (detail): Apollo and the nine muses

References

Citations

- Schlierbach: Österreichisches Musiklexikon.

- Geschichte: Stift Schlierbach.

- Büsching & Murdoch 1762, p. 184.

- Suckale 2008, p. 115.

- Patrouch 2000, p. 115.

- Fabian 2003.

- Patrouch 2000, p. 199.

- Röhlig 1957, p. 144.

- MobileReference 2007, p. 776.

- Mag. P. Martin Spernbauer... Stift.

- Aktuelles: Stift Schlierbach.

- Harbutt 2009, p. 238.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stift Schlierbach. |

Sources

- "Aktuelles". Stift Schlierbach. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- Büsching, Anton Friedrich; Murdoch, Patrick (1762). A New System of Geography: Part of Germany, viz. Bohemia, Moravia, Lusatia, Austria, Burgundy, Westphalia, and the circle of the Rhine. A. Millar. Retrieved 2013-12-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fabian, Bernhard (2003). "Bibliothek des Zisterzienserstiftes". Handbuch der historischen Buchbestände in Deutschland. Olms Neue Medien. Retrieved 2013-12-06.

- "Geschichte". Stift Schlierbach. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- Harbutt, Juliet (2009-10-05). The World Cheese Book. DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7566-6218-9. Retrieved 2013-12-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Mag. P. Martin Spernbauer wurde zum neuen Administrator des Stiftes Schlierbach gewählt". Stift Schlierbach. 18 November 2008. Retrieved 2013-12-06.

- MobileReference (2007-01-01). Travel Brussels, Belgium. FREE General Information, Basic Phrasebook, and a Map in the Trial Version. MobileReference. ISBN 978-1-60501-056-4. Retrieved 2013-12-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patrouch, Joseph F. (2000). A Negotiated Settlement: The Counter-Reformation in Upper Austria Under the Habsburgs. BRILL. ISBN 978-0-391-04099-1. Retrieved 2013-12-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Röhlig, Ursula (1957). "Carlone, Pietro Francesco". Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German). 3. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. Retrieved 2013-12-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Schlierbach". Österreichisches Musiklexikon, Kommission für Musikforschung. Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. 2013. ISBN 978-3-7001-3077-2. Retrieved 2013-12-06.

- Suckale, Robert (2008-12-15). "An unrecognized statuette of the Virgin Mary be a Vienna court artist, ca. 1350". Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 53/54: Spring and Autumn 2008. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-87365-840-9. Retrieved 2013-12-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)