Schism of Montaner

In the Schism of Montaner between 1967 and 1969, almost all residents of the Italian village of Montaner renounced Catholicism and embraced the Eastern Orthodox Church. This was due to a disagreement with the bishop of Vittorio Veneto, Albino Luciani, the future Pope John Paul I, over the appointment of the local priest.

Background

Montaner is a frazione in the municipality of Sarmede in the Province of Treviso, Italy. On December 13, 1966, Giuseppe Faè, the parish priest, died.[1] Faè, who had served the community for forty years, had proven popular with the people of Montaner.[1] He aided in the obtaining electricity and running water for the village, the construction of a new school, and even aided in the organization of anti-fascist resistance to the German Occupation.[2] After his death, the bishop of Vittorio Veneto decided to appoint Giovanni Gava as the new priest, which was unpopular among the villagers. They instead supported Antonio Botteon, who, for a long time, had assisted the old priest.[3] As a last resort, Botteon was asked to become the vice-rector of the parish.

On January 21st, 1967, the new priest arrived in town, however, the night before his arrival, the townspeople erected a wall blocking the entrance of the church, and a mob of townspeople prevented him from carrying out his work.[3]

Luciani replied that for a village as small as Montaner, one priest was enough, while noting that priests are not elected by the people but appointed by their bishop. The bishop appointed a former Franciscan as a temporary rector, Father Casimiro from Monselice, again failing to meet the citizens' requests.

Luciani's final decision was to appoint a new rector, Pietro Varnier. But on September 12, 1967, disgruntled citizens locked Varnier in the attic of the rectory. Luciani then arrived in Montaner, escorted by police, and removed the Blessed Sacrament from the Church, leaving the Church unblessed.

The schism

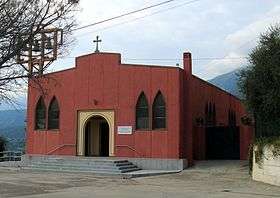

The people then founded the Orthodox Church of Montaner. On December 26, 1967, the first Divine Liturgy was celebrated with the Orthodox Byzantine rite. The Orthodox priest, Claudio Vettorazzo, was permanently installed in June 1969 and on September 7, 1969, the Orthodox church was blessed. Residents of the village recall that the initial time period after the schism resulted in "hatred" and "confusion" within the village.[4]

In 1994, Vettorazzo was imprisoned because of legal and financial problems.[5]

Only after 1998 was the Orthodox Church of Montaner officially recognized by the Patriarchate of Constantinople, to use the Byzantine Rite. In 2000, a nunnery associated with the church was founded.

Today, the Catholic and Orthodox communities still exist within the village, though divisions remain.[4] The Orthodox parish is also frequented by immigrants from Eastern Europe.

See also

References

- Conversion in the age of pluralism. Giordan, Giuseppe. Leiden: Brill. 2009. p. 246. ISBN 978-90-474-4494-7. OCLC 607552761.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Conversion in the age of pluralism. Giordan, Giuseppe. Leiden: Brill. 2009. pp. 246–247. ISBN 978-90-474-4494-7. OCLC 607552761.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Conversion in the age of pluralism. Giordan, Giuseppe. Leiden: Brill. 2009. p. 247. ISBN 978-90-474-4494-7. OCLC 607552761.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Conversion in the age of pluralism. Giordan, Giuseppe. Leiden: Brill. 2009. pp. 250–251. ISBN 978-90-474-4494-7. OCLC 607552761.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Sexe et drogue dans la maison de l'évêque

Further reading

- Valentina Ciciliot, Il caso Montaner. Un conflitto politico tra chiesa cattolica e chiesa ortodossa, Venezia - Ca' Foscari, 2004. (in Italian)

External links

- The schisme of Montaner in Youtube (in Italian)

- Reportage of TV RAI about Montaner (in Italian)