Saut-du-Tarn Steel Works

The Saut-du-Tarn Steel Works (French: Société des Hauts-Fourneaux, forges et aciéries du Saut-du-Tarn) was a steel maker in Saint-Juéry, Tarn, France. It originated with Léon Talabot et Compagnie, founded by Léon Talabot in 1824. The factory specialized in manufacturing steel handtools such as files, scythes and sickles, but later moving into manufacture of machine tools. It closed in 1983 and was liquidated in 1984. Several successor companies acquired some of the facilities and continue to operate.

Native name | Société des Hauts-Fourneaux, forges et aciéries du Saut-du-Tarn |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | |

| Industry | Iron and steel |

| Fate | Liquidated |

| Founded | 1824 |

| Founder | Léon Talabot |

| Defunct | 1984 |

| Headquarters | , France |

Number of employees | 220 (1864) |

| Parent | Tyco International |

Origins (1824–81)

The factory in Saint-Juery, Tarn, was founded in 1824 as L. Talabot & Cie.[1] The factory was near to Albi, Tarn, specializing in steel production and the manufacture of tools. It was located beside a rocky gorge on the Tarn river, holding a falls where the water drops by about 18 metres (59 ft).[2] The factory used the river as a source of power, and produced hardware such as files and scythes.[3] The first rolling mills were installed in 1831.[4] The Société Léon Talabot was formed in May 1832 and was restructured in 1840.[5]

The Société de Mokta el Hadid was established in Algeria in 1863. Plans were drawn up to combine the Mokta el Hadid mines with the Firminy, Loire, steelworks, the Gard coal mines and the Saut-du-Tarn steelworks. 20 million francs of capital would be needed, including 8 million of fresh capital for upgrades at the various sites. These plans dragged out and came to nothing.[6] In 1870, the Société Léon Talabot was liquidated and on 11 March 1870 sold to the Société Anonyme des Aciéries du Tarn.[5] The products were marketed under the TALABOT and SDT brands.[2]

Peak period (1881–1950)

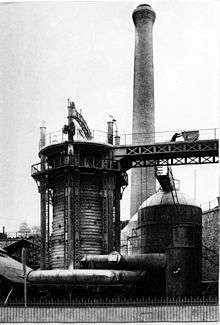

In 1881 a rolling mill hall was built with two mills.[4] In 1882 a coke-fired blast furnace was installed for production of cast iron.[3] The 1886 film Carmaux, défournage du coke by Lumière is a one-minute sequence of men lifting a large coal block out of a smelter in Carmaux.[7] The first hydroelectric power station was built in 1898, supplying electricity to the factory and the village.[3]

In 1904 there were 1,545 workers in factories that covered 18 hectares (44 acres) The hydraulic power plant was delivering 3,000 horsepower (2,200 kW).[1] In 1913 the company had assets of 11.2 million francs.[8] New rolling mills were installed in 1913.[4] During the period from 1884 to 1934, many peasants came to work in the steel works from Cahuzaguet, Saint-Grégoire, Arthès, les Avalats and Marsal. Many settled in Saint-Juéry, which grew from 1,400 inhabitants in the 19th century to 7,000 inhabitants today.[9] By 1925 there were 2,500 workers.[3]

Jacques de Nervo began his career in 1919 by joining the Société du Saut-du-Tarn. He became general secretary of the company in 1921, a director, then president and chief executive officer.[10] The Centre des jeunes patrons was created due to the concerns of private business owners after the Popular Front won the 1936 elections. The honorary president was Baron Jacques de Nervo, vice-president of the Société du Saut-du-Tarn and a member of the board of the Union des industries et métiers de la métallurgie (UIMM).[11]

A January 1948 illustrated catalog lists a wide range of scythes, sickles and other edged tools.[12] The company made Talabot-brand sickles (faucilles à dents) with fine serrated teeth. These sickles would have a series of ridges on the blade at an angle of about 45% to the cutting edge. The ridges ensured the serrations remained when the tool was sharpened.[13]

Decline and closure (1950–83)

Starting in 1950, production of hardware was reduced and the factory began to manufacture machine tools.[2] A Swedish rolling mill was installed in 1960 for manufacture of steel for files.[4] By 1960, the Talabot-brand tooth sickles were mainly sold in North Africa rather than France.[14] Claude Dupuy, Archbishop of Albi, intervened in the threatened closure of the Saut-du-Tarn steel plant in 1968.[15] In 1978 the factory produced 11,696 tons of laminated steel, 1,894 tons of iron, 3,511,500 files, 1,203 tons of tools and more than 4,000 valves for the hydraulic and oil industry.[9] With the collapse of the iron and steel industry, the factory closed in 1983.[3] Those over 50 years old received 90% of their gross salary before retirement.[9] The Saut du Tarn company was liquidated in 1984.[4]

Five new companies were created in 1984, including the ALST (Aciéries et Laminoirs du Saut du Tarn), later renamed the AEDT (Aciers et Energies du Tarn).[4] As of 2015, there were still steel enterprises in the village of Saint-Juéry that employed over 250 people making hydraulic and oil valves, agricultural tools and speciality steel.[9] A museum is located in the former industrial site in the building that housed the first hydroelectric plant.[2]

Notes

- Hauts-Fourneaux, Forges & Aciéries ... industrie.lu.

- Présentation – Musée du Saut du Tarn.

- Patrimoine – Saint-Juéry.

- Historique – AEDT.

- Bourgade, Charbonnieras & Fonvieille 2012.

- Gille 1968, p. 183.

- Auguste and Louis Lumière 1886.

- Smith 1998, p. 58.

- MF 2015.

- Nervo de, Jacques – Patrons de France.

- Bot 2012, p. 100.

- Société Anonyme des Forges ... Baryonyx.

- Brunhes-Delamarre 1960, p. 182.

- Delamarre, Haudricourt & Chaurand 1960, p. 67.

- Nelidoff 1974, pp. 232–233.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Société des Aciéries du Saut du Tarn. |

Sources

- Auguste and Louis Lumière (1886), Carmaux, Defournage du Coke, retrieved 2017-09-07 – via YouTube

- Bot, Florent Le (April–June 2012), "La naissance du Centre des jeunes patrons (1938-1944): Entre réaction et relève", Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire, Sciences Po University Press (114, Patrons et patronat en France au 20 e siècle), JSTOR 23326298

- Bourgade, Brigitte; Charbonnieras, Agnès; Fonvieille, Pascale (2012), 63 J - Archives industrielles du Saut-du-Tarn, entreprise de métallurgie à Saint-Juéry (1817-1982) (in French), Albi, retrieved 2017-09-07

- Brunhes-Delamarre, Mariel J.- (1960), "A PROPOS DES FAUCILLES A DENTS", Arts et traditions populaires (in French), Presses Universitaires de France, 8, JSTOR 41003090

- Delamarre, Mariel J.-Brunhes; Haudricourt, André G.; Chaurand, Jacques (1960), "INSTRUMENTS AGRICOLES ET ARTISANAUX PRÉ-INDUSTRIELS DU MARLOIS ET DE LA THIERACHE", Arts et traditions populaires, Presses Universitaires de France, 8, JSTOR 41003079

- Gille, Bertrand (1968), La Sidérurgie française au XIXe siècle: Recherches histioriques (in French), Librairie Droz, ISBN 978-2-600-04046-4, retrieved 2017-08-13

- "Hauts-Fourneaux, Forges & Aciéries du Saut-du-Tarn", industrie.lu (in French), retrieved 2017-09-07

- Historique (in French), AEDT: Aciers et Energies du Tarn, archived from the original on 2017-09-08, retrieved 2017-09-07

- MF (13 September 2015), "A Saint-Juéry, le Saut du Tarn est encore vivant", La Depeche (in French), retrieved 2017-09-07

- Nelidoff, Philippe (1974). "Mgr Claude Dupuy". Archives diocésaines d’Albi 1D9 SR Albi 1962-1974 (in French). Archived from the original on 2015-02-07. Retrieved 2015-06-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Nervo de, Jacques", Patrons de France (in French), SIPPAF, retrieved 2017-09-07

- Patrimoine (in French), Saint-Juéry, retrieved 2017-09-07

- "Présentation", Musée du Saut du Tarn (in French), Bloom multimédia, retrieved 2017-09-07

- Smith, Michael S. (Spring 1998), "Putting France in the Chandlerian Framework: France's 100 Largest Industrial Firms in 1913", The Business History Review, The President and Fellows of Harvard College, 72 (1), JSTOR 3116595

- Société Anonyme des Forges et Aciéries du Saut du Tarn, January 1948, Baryonyx Knife Co., retrieved 2017-09-07