Sarashina Nikki

The Sarashina Diary (更級日記, Sarashina Nikki) is a memoir written by the daughter of Sugawara no Takasue, a lady-in-waiting of Heian-period Japan. Her work stands out for its descriptions of her travels and pilgrimages and is unique in the literature of the period, as well as one of the first in the genre of travel writing. Lady Sarashina was a niece on her mother's side of Michitsuna's Mother, author of another famous diary of the period, the Kagerō Nikki (whose personal name has also been lost).

Extracts from the work are part of Japanese high school students' classical Japanese studies.

The author and the book's content

The daughter of Sugawara Takasue (also known as Lady Sarashina) wrote her memoirs in her later years. She was born in 1008 CE and in her childhood traveled to the provinces with her father, an assistant governor, and back to the capital some years later. Her remembrances of the long journey back to the capital (three months) are unique in Heian literature, if terse and geographically inaccurate. Here she describes Mount Fuji, then an active volcano:

It has a most unusual shape and seems to have been painted deep blue; its thick cover of unmelting snow gives the impression that the mountain is wearing a white jacket over a dress of deep violet.[1]

Her memoirs start with her childhood days, when she delighted in reading tales, and prayed to be able to read the Tale of Genji from beginning to end. She records her joy when presented with a complete copy, and how she dreamed of living a romance like those described in it. When her life does not turn out as well as she had hoped, she blames her addiction to tales, which made her live in a fantasy world and neglect her spiritual growth. These records are impressive memories of Lady Sarashina’s travel and dreams, and of her day-to-day life.

She spent her youth living at her father's house. In her thirties she married Tachibana Toshimichi, a government official, and from time to time seems to have served at court. At the end of her memoirs she expresses her deep grief at her husband's death. Heian literature conventionally expresses sorrow at the shortness of life, but Lady Sarashina conveys her pain and regrets at the loss of those she has loved with passionate directness. She stopped writing at some time in her fifties and no details about her own death are known.

Lady Sarashina's birth name is unknown, and she is called either Takasue's daughter or Lady Sarashina. Sarashina is a geographical district never mentioned in the diary, but it is alluded to, in a reference to Mount Obasute, also known as Mount Sarashina, in one of the book's poems (itself an adaptation of a more ancient poem). This, and the fact that her husband's last appointment was to the province of Shinano (Nagano), probably led to the use by later scholars of "Sarashina" as a point of identification of the text and its author.

Manuscripts

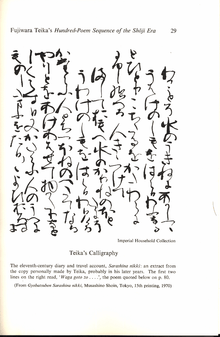

The most authoritative copy of Sarashina Nikki is one produced by Fujiwara no Teika in the 13th century, some two hundred years after Lady Sarashina wrote the original. Teika copied Lady Sarashina's work once, but his first transcription was borrowed and lost; the manuscript he worked from was itself a second-generation copy of a lost transcription.[2] To compound the problems, sometime in the 17th century Teika's transcription was re-bound, but the binder changed the order of the original in seven places, making the diary less valuable and more difficult for scholars to understand. In 1924, Nobutsuna Sasaki and Kōsuke Tamai, two classical literature scholars, examined the original Teika manuscript and finally discovered what had happened, leading to a reevaluation of Sarashina's work. It is from this correctly re-ordered version that all modern versions are made.

Notes

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Morris, Ivan, trans.: As I Crossed a Bridge of Dreams: Recollections of a Woman in Eleventh-Century Japan. Penguin Classics, 1989 (reprint). ISBN 0-14-044282-0 (ISBN ) or ISBN 978-0-14-044282-3 (ISBN )

- Nishishita, Kyoichi. Commentary. Sarashina Nikki. Rev. Kyoichi Nishishita. 1930. Tokyo: Iwanami, 1963.