Santa Anna (1522 ship)

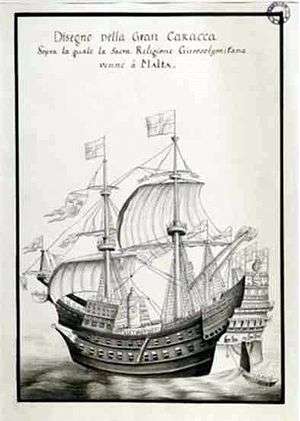

Santa Anna was an early 16th-century carrack of the navy of the Knights Hospitaller. The war ship was celebrated for her many modern features. While some authors view her lead sheathed hull as an early form of ironclad,[1] others regard it primarily as a means to improve her watertightness.[2]

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Launched: | 21 December 1522 |

| Fate: | Abandoned 1540 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Carrack |

| Armament: | 50 guns |

Career

Santa Anna was launched in Nice on 21 December 1522,[2] one day before the Knights Hospitaller surrendered at the siege of Rhodes (1522) under honorable terms.

Santa Anna's underwater hull was completely sheathed with lead plates. Above the waterline two of the six decks were also armoured with lead plates, which were fastened by bronze nails to the wooden hull. Santa Anna was designed to accommodate 500 marines besides her sailors and she featured large below-deck cabins and messes for her officers. The carrack housed a forge, where three weapon smiths could do maintenance work at sea. The ship even had several ovens and its own mill, in order to provide the crew with fresh bread. The ship also featured a garden on board with flowers hanging down from the stern gallery in boxes.[1]

In 1531, Santa Anna routed on its own an Ottoman squadron of 25 ships.[3] One year later, the carrack took part in the expedition against the Peloponnese under the command of Andrea Doria, during which Koroni, Patras and the Turkish fortresses protecting the entry to the Gulf of Corinth were seized.[3] In 1535 Santa Anna fought in the successful campaign of the Spanish fleet under Charles V against Tunis, where the Spaniards managed to capture over 100 ships of the Barbary corsairs.[4] Her firepower contributed significantly in the assault on the fortress La Goulette which controlled the entry to the harbour.[3]

Temporarily, the carrack was also employed as a wheat freighter, with an impressive capacity of up to 900 tons.[1] Only eighteen years after her launch, Santa Anna was stripped and abandoned in 1540 on the order of Grand Master Juan de Homedes y Coscon.[2]

Citations and references

Citations

- Brennecke 1986, p. 138.

- Tailliez, D. "Les Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean de Jérusalem à Nice et Villefranche" [The Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem in Nice and Villefranche]. La Darse Villefranche-sur-mer (in French). Association pour la Sauvegarde du Patrimoine Maritime de Villefranche-sur-Mer. Archived from the original on 2010-07-30.

- Pemsel, pp. 144ff..

- Brennecke 1986, pp. 144ff..

References

- Brennecke, Jochen (1986). Geschichte der Schiffahrt (2nd ed.). Künzelsau. ISBN 3-89393-176-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pemsel, Helmut. Seeherrschaft. Eine maritime Weltgeschichte von den Anfängen bis 1850. 1. Bernard & Graefe Verlag. pp. 144ff. ISBN 3-89350-711-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

See also

- List of ships of the line of Malta

- Finis Bellis

External links

- Tailliez, D. "Les Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean de Jérusalem à Nice et Villefranche" [The Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem in Nice and Villefranche] (PDF). La Darse Villefranche-sur-mer (in French). Association pour la Sauvegarde du Patrimoine Maritime de Villefranche-sur-Mer. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2007-08-18.