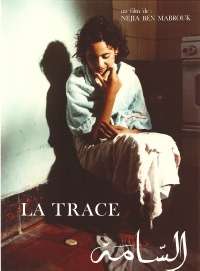

Sama (film)

Sama (English title: The Trace) is a 1988 Tunisian feature film directed by Néjia Ben Mabrouk. It is the first fictional feature film directed by a woman that was released in Tunisia.[1] The film deals with themes of gender and education.

| Sama | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Néjia Ben Mabrouk |

| Screenplay by | Néjia Ben Mabrouk |

| Starring | Fatma Khwmiei, Mouna Noureddine, Basma Tajine |

| Music by | François Gaudard |

| Cinematography | Marc-André Batigne |

| Edited by | Moufida Tlatli |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | Tunisia |

| Language | Arabic |

Plot

The mother (Mouna Noureddine) gives her daughter Sabra (Fatma Khemiri) an oval stone to protect her from men until her wedding day. The stone is locked in a jewelry box, symbolizing Sabra being locked in society against her consent.[2]:382–3 While seeking and education in the male-dominated Tunisian society, Sabra fears being reduced to society's traditional roles. Flashbacks to her childhood reveal how her mother taught her to be wary of men. Sabra overcomes societal barriers and makes it into university and studies for her exams by candlelight. However, when her professor gives her a failing grade, Sabra decides that she has to leave. With her mother's support, Sabra continues her studies exiled in Europe.[3]

Production

Ben Mabrouk planned on making a documentary for her debut, but encountered some problems in Brussels. She found that many Tunisians did not want to talk openly about their problems.[2]:363 From 1979 to 1980, Ben Mabrouk wrote the script for Sama.[3] Ben Mabrouk looked for foreign producers from Algeria, Belgium, and France, all of which rejected her script. Finally, she received production support from the German company ZDF and the Tunisian company SATPEC.[2]:380 Sama was filmed in 1982, but a dispute with the SATPEC delayed the film's release for six years,[4] later described as "petty bureaucratic red-tape,"[5] Concerning the filming, one reviewer found that it was "shot grittily in locations which look authentic, skimping on lighting to the point where it is hard to distinguish between details on the screen."[6]

Critical response

When Sama premiered at the Carthage Film Festival, it reportedly caused a stir among audiences, particularly the female members who protested the film's open portrayal of private practices.[2]:18 One reviewer noted that the film broke "an incredible taboo" by Tunisian standards.[2]:380–1 Ben Mabrouk won the Caligari Prize at the 1989 International Forum of New Cinema of the Berlin International Film Festival for directing Sama.[7] The Arabic emancipatory cinema d'auteur consider this film a classic.[2]:18 The film was screened at the London Feminist Film Festival on August 18, 2018.[8]

Marie-Pierre Macia praised the film's presentation of its main protagonist, writing, "The Trace is content to introduce us to a complex protagonist—it does not insist we identify with her although her story captivates and moves us."[9] A review from Variety noted some of Sama's shortcomings, saying that they could be attributed to "the name of the production company (No Money) and the time it took to shoot this film." The reviewer called it "a typical portrait of a woman's condition in a male-dominated society," and "first and foremost a militant tract."[6] Simone Mahrenholz praised the flashbacks to Sabra's childhood, saying they "show us in painful clarity the conditioning of girls."[2]:383

Themes

A reviewer from Variety thought that the film is "bound to attract the attention of ethnographers and socio-political activists," because of its themes.[6] Hayet Gribaa examined the contrast between the knowledge seeking Sabra and her illiterate mother and their similarities as they try to respect each other.[2]

The film's title refers to a scar on Sabra's mother's forehead, the last trace of a traditional tattoo removed by acid.[10] The imagery of Sama is divided between the hostile school and streets, and the protective interior of the home; both respectively defined as the male and female environments.[3]

References

- Leaman, Oliver (16 December 2003). Companion Encyclopedia of Middle Eastern and North African Film. Routledge. p. 505. ISBN 978-1-134-66252-4.

- Hillauer, Rebecca (2005). "Ben Mabrouk, Néjia (1949–)". Encyclopedia of Arab Women Filmmakers. Translated by Brown, Allison. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. pp. 18, 380–1. ISBN 9789774249433.

- Shafik, Viola (2007). "Cultural Identity and Gender". Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity. Cairo, Egypt: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 204. ISBN 9789774160653.

- Sloan, Jane (2007). Reel Women: An International Directory of Contemporary Feature Films about Women. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810857384.

- Assa, Sonia (2009). "No Place Like Home: Domestic Space and Women's Sense of Self in North African Cinema" (PDF). Al-Raida Journal (124): 26–7.

- Edna (24 August 1988). "Film reviews: Sama". Variety. 332 (5): 12.

- "Berlinale Forum". Arsenal. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Pakett, Zoe (8 August 2018). "London Feminist Film Festival tells stories of activism and daily life from women around the world". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- Marie Pierre, Macia. "The Trace". San Francisco Film Festival. San Francisco Film Society. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Nelmes, Jill; Selbo, Jule (29 September 2015). Women Screenwriters: An International Guide. Springer. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-1-137-31237-2.