Sam Sheppard

Samuel Holmes Sheppard (December 29, 1923 – April 6, 1970) was an American neurosurgeon. He was exonerated in 1966, having been convicted of the 1954 murder of his wife, Marilyn Reese Sheppard.[1] The case was controversial from the beginning, with extensive and prolonged nationwide media coverage.

Sam Sheppard | |

|---|---|

| Born | Samuel Holmes Sheppard December 29, 1923 |

| Died | April 6, 1970 (aged 46) Columbus, Ohio, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Gardens (1970–1997) Knollwood Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Hanover Case Western Reserve University of California Irvine |

| Occupation | Osteopathic physician-neurosurgeon, professional wrestler |

| Spouse(s) | Marilyn Reese

( m. 1945; died 1954)Ariane Tebbenjohanns

( m. 1964; div. 1969)Colleen Strickland ( m. 1969) |

| Children | 1 |

| Conviction(s) | Murder (overturned) |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment (overturned) |

The U.S. Supreme Court determined that the "carnival atmosphere" surrounding Sheppard's first trial had made due process impossible; after ten years in prison he was acquitted at a second trial.

Early life and education

Sheppard was born in Cleveland, Ohio, the youngest of three sons of Richard Allen Sheppard, D.O. He attended Cleveland Heights High School where he was an excellent student and was active in American football, basketball, and track; he was class president for three years. Sheppard met his future wife, Marilyn Reese, while in high school. Although several small Ohio colleges offered him athletic scholarships, Sheppard chose to follow the lead of his father and older brothers and pursued a career in osteopathic medicine. He enrolled at Hanover College in Indiana to study pre-osteopathic medical courses, then took supplementary courses at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Sheppard finished his medical education at the Los Angeles Osteopathic School of Physicians and Surgeons (now University of California Irvine) and was awarded the Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O) degree.

Sheppard completed his internship and a residency in Neurosurgery at Los Angeles County General Hospital. He married Marilyn Reese on February 21, 1945, in Hollywood, California. A few years later he returned to Ohio and joined his father's growing medical practice at Bay View Hospital.

Murder of Marilyn Reese Sheppard

On the night of July 3, 1954, Sheppard and Marilyn were entertaining neighbors at their lakefront home (demolished in 1993)[2] on Lake Erie at 28944 Lake Road[3] in Bay Village, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland, just west of the city. The property itself abutted the shore of Lake Erie, near the west end of Huntington Reservation. While they were watching the movie Strange Holiday, Sheppard fell asleep on the daybed in the living room. Marilyn walked the neighbors out.

In the early morning hours of July 4, 1954, Marilyn Sheppard was bludgeoned to death in her bed with an unknown instrument. The bedroom was covered with blood spatter and drops of blood were found on floors throughout the house. Some items from the house, including Sam Sheppard's wristwatch, keychain and key, and fraternity ring, appeared to have been stolen.[4] They were later found in a canvas bag in shrubbery behind the house.[4] According to Sheppard, he was sleeping soundly on a daybed when he heard the cries from his wife. He ran upstairs where he saw a “white form” in the bedroom and then he was knocked unconscious. When he awoke, he saw the person downstairs, chased the intruder out of the house down to the beach where they tussled and Sheppard was knocked unconscious again.

At 5:40 am, a neighbor received an urgent phone call from Sheppard who pleaded for him to come to his home. When the neighbor and his wife arrived, Sheppard was found shirtless and his pants were wet with a bloodstain on the knee. Authorities arrived shortly thereafter. Sheppard seemed disoriented and in shock.[5] The family dog was not heard barking to indicate an intruder, and their seven-year-old son, Sam Reese "Chip" Sheppard, was asleep in the adjacent bedroom throughout the incident.[6]

First trial

Media

Sheppard's trial began October 18, 1954. The murder investigation and the trial were notable for the extensive publicity. Some newspapers and other media in Ohio were accused of bias against Sheppard and inflammatory coverage of the case, and were criticized for immediately labeling him the only viable suspect. A federal judge later criticized the media, "If ever there was a trial by newspaper, this is a perfect example. And the most insidious example was the Cleveland Press. For some reason that newspaper took upon itself the role of accuser, judge and jury."[7]

It appeared that the local media influenced the investigators. On July 21, 1954, the Cleveland Press ran a front-page editorial titled "Do It Now, Dr. Gerber" which called for a public inquest. Hours later, Dr. Samuel Gerber, the coroner investigating the murder, announced that he would hold an inquest the next day.[8] The Cleveland Press ran another front-page editorial titled "Why Isn't Sam Sheppard in Jail?" on July 30 which was titled in later editions, "Quit Stalling and Bring Him In!"[9][10] That night, Sheppard was arrested for a police interrogation.[11]

The local media ran salacious front-page stories inflammatory to Sheppard which had no supporting facts or were later disproved. During the trial, a popular radio show broadcast a report about a New York City woman who claimed to be his mistress and the mother of his illegitimate child. Since the jury was not sequestered, two of the jurors admitted to the judge that they heard the broadcast but the judge did not dismiss them.[12] From interviews with some of the jurors years later, it is likely that jurors were contaminated by the press before the trial and perhaps during it.[13] The U.S. Supreme Court later called the trial a "carnival atmosphere".[14]

Prosecution's theory

The high-profile nature of the case proved to be a boon to lead prosecutor John J. Mahon, who was running for a seat on the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas as the trial began. Mahon won his seat, and served until his death on January 31, 1962. Prosecutors learned during their investigation and revealed at trial that Sheppard had carried on a three-year-long extramarital affair with Susan Hayes, a nurse at the hospital where Sheppard was employed. The prosecution argued that the affair was Sheppard's motive for killing his wife. Mahon made the most of the case in the absence of any direct evidence against the defendant, other than that he was inside the house when Marilyn Sheppard was killed. Mahon emphasized the inconsistencies in Sam Sheppard's story and that he could not give an accurate description of the intruder in his house.

Other issues brought up at trial involved why there was no sand in his hair when Sheppard claimed to have been sprawled at the beach, and Sheppard's missing T-shirt, which the prosecutor speculated would or should contain some of Sheppard's blood (having been in an alleged struggle with the perpetrator). However, Prosecutor Mahon chose to make these assertions despite no T-shirt ever being found or presented as evidence. Also, part of the prosecution's case centered around (speculative) questions like why a burglar would first take the belongings in the canvas bag, only to later ditch them in bushes outside the Sheppard home. It was under these circumstances that Mahon openly speculated Sheppard had staged the crime scene. Lack of a murder weapon posed problems for the prosecution, but Cuyahoga County Coroner Samuel R. Gerber nearly circumvented this discrepancy by testifying that a blood imprint found on the pillow beneath Marilyn Sheppard's head was made by a "two-blade surgical instrument with teeth at the end of each blade" such as a scalpel. Inexplicably, Sheppard's lawyers left this vague assertion unchallenged. Sheppard's lawyer was denied access to the physical evidence by the judge and therefore could not argue any assertions as to blood droplets, murder weapon marks, blood spatter, physical marks on the body, etc.

Defense strategy

Sheppard's attorney, William Corrigan, argued that Sheppard had severe injuries and that these injuries were inflicted by the intruder. Corrigan based his argument on the report made by neurosurgeon Dr. Charles Elkins, M.D., who examined Sheppard and found he had suffered a cervical concussion, nerve injury, many absent or weak reflexes (most notably on the left side of his body), and injury in the region of the second cervical vertebra in the back of the neck. Dr. Elkins stated that it was impossible to fake or simulate the missing reflex responses.

The defense further argued the crime scene was extremely bloody, yet the only blood evidence appearing on Sheppard was a bloodstain on his trousers. Corrigan also argued two of Marilyn's teeth had been broken and that the pieces had been pulled from her mouth, suggesting she had possibly bitten her assailant. He told the jury that Sheppard had no open wounds. (Some observers have questioned the accuracy of claims that Marilyn Sheppard lost her teeth while biting her attacker, arguing that her missing teeth are more consistent with the severe beating Marilyn Sheppard received to her face and skull.[15]) However, as criminologist Paul L. Kirk later pointed out, if the beating had broken Mrs. Sheppard's teeth, pieces would have been found inside her mouth, and her lips would have been severely damaged, which was not the case.[16]

Sheppard took the stand in his own defense, testifying that he had been sleeping downstairs on a daybed when he awoke to his wife's screams.

I think that she cried or screamed my name once or twice, during which time I ran upstairs, thinking that she might be having a reaction similar to convulsions that she had in the early days of her pregnancy. I charged into our room and saw a form with a light garment, I believe, at that time grappling with something or someone. During this short period I could hear loud moans or groaning sounds and noises. I was struck down. It seems like I was hit from behind somehow but had grappled this individual from in front or generally in front of me. I was apparently knocked out. The next thing I knew, I was gathering my senses while coming to a sitting position next to the bed, my feet toward the hallway. ... I looked at my wife, I believe I took her pulse and felt that she was gone. I believe that I thereafter instinctively or subconsciously ran into my youngster's room next door and somehow determined that he was all right, I am not sure how I determined this. After that, I thought that I heard a noise downstairs, seemingly in the front eastern portion of the house.[17]

Sheppard ran back downstairs and chased what he described as a "bushy-haired intruder" or "form" down to the Lake Erie beach below his home, before being knocked out again. The defense called eighteen character witnesses for Sheppard, and two witnesses who said that they had seen a bushy-haired man near the Sheppard home on the day of the crime.

Verdict

On December 21, after deliberating for four days, the jury found Sheppard guilty of second-degree murder.[18] He was sentenced to life in prison.[19] On January 7, 1955, shortly after his conviction, Sheppard was told that his mother, Ethel Sheppard, had committed suicide by gunshot.[20] Eleven days later, Sheppard's father, Dr. Richard Sheppard, died of a bleeding gastric ulcer and stomach cancer.[21] Sheppard was permitted to attend both funerals but was required to wear handcuffs.[22]

In 1959, Sheppard voluntarily took part in cancer studies by the Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, allowing live cancer cells to be injected into his body.[23]

On February 13, 1963, Sheppard's father-in-law, Thomas S. Reese, committed suicide in an East Cleveland, Ohio, motel.[20][24][25]

Appeals and retrial

Appeals

Sheppard's attorney William Corrigan spent six years making appeals but all were rejected. On July 30, 1961, Corrigan died and F. Lee Bailey took over as Sheppard's chief counsel. Bailey's petition for a writ of habeas corpus was granted on July 15, 1964, by a United States district court judge who called the 1954 trial a "mockery of justice" that shredded Sheppard's Fourteenth Amendment right to due process. The State of Ohio was ordered to release Sheppard on bond and gave the prosecutor 60 days to bring charges against him, otherwise the case would be dismissed permanently.[26] The State of Ohio appealed the ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals Court for the Sixth Circuit, which on March 4, 1965 reversed the federal judge's ruling.[27] Bailey appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case in Sheppard v. Maxwell. On June 6, 1966, the Supreme Court, by an 8-to-1 vote, struck down the murder conviction. The decision noted, among other factors, that a "carnival atmosphere" had permeated the trial, and that the trial judge, Edward J. Blythin,[28] who had died in 1958, was biased against Sheppard because Judge Blythin had refused to sequester the jury, did not order the jury to ignore and disregard media reports of the case, and when speaking to newspaper columnist Dorothy Kilgallen shortly before the trial started said, "Well, he's guilty as hell. There's no question about it."

Sheppard served ten years of his sentence. Three days after his 1964 release, he married Ariane Tebbenjohanns, a German divorcee who had corresponded with him during his imprisonment. The two had been engaged since January 1963. Tebbenjohanns endured her own bit of controversy shortly after the engagement had been announced, confirming that her half-sister was Magda Ritschel, the wife of Nazi propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels. Tebbenjohanns emphasized that she held no Nazi views. On October 7, 1969, Sheppard and Tebbenjohanns divorced.[29]

Retrial

Jury selection began October 24, 1966, and opening statements began eight days later. Media interest in the trial remained high, but this jury was sequestered. The prosecutor presented essentially the same case as was presented twelve years earlier. Bailey aggressively sought to discredit each prosecution witness during cross-examination. When Coroner Samuel Gerber testified about a murder weapon which he described as a "surgical weapon", Bailey led Gerber to admit that they never found a murder weapon[30] and had nothing to tie Sheppard to the murder. In his closing argument, Bailey scathingly dismissed the prosecution's case against Sheppard as "ten pounds of hogwash in a five-pound bag".

Unlike in the original trial, neither Sheppard nor Susan Hayes took the stand, a strategy that proved to be successful.[30] After deliberating for 12 hours, the jury returned on November 16 with a "not guilty" verdict. The trial was very important to Bailey's rise to prominence among American criminal defense lawyers. It was during this trial that Paul Kirk presented the bloodspatter evidence he collected in Sheppard's home in 1955 which suggested that the murderer was left-handed (Sheppard was right-handed) proved crucial to his acquittal.[30]

Three weeks after the trial, Sheppard appeared as a guest on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

After his acquittal, Sheppard helped write the book Endure and Conquer, which presented his side of the case and gave insight into his years in prison.

Professional wrestling career

| Sam Sheppard | |

|---|---|

| Birth name | Samuel Holmes Sheppard |

| Born | December 29, 1923 Cleveland, Ohio, United States |

| Died | April 6, 1970 (aged 46) Columbus, Ohio, United States |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Ring name(s) | Sam Sheppard |

| Billed weight | 195 lb (88 kg)[31] |

| Trained by | George Strickland[31] |

| Debut | August 1969[32] |

Sheppard's friend and soon-to-be father-in-law, professional wrestler George Strickland, introduced him to wrestling and trained him for it. He debuted in August 1969 at the age of 45 as "Killer" Sam Sheppard, wrestling Wild Bill Scholl.[32]

Sheppard wrestled over 40 matches before his death in April 1970, including a number of tag team bouts with Strickland as his partner.[33] His notoriety made him a strong draw.[34]

During his career, Sheppard used his anatomical knowledge to develop a new submission hold, the "mandible claw". It was popularized by professional wrestler Mankind in 1996.[35]

Late medical practice, remarriage, and death

After his release from prison, Sheppard opened a medical office in the Columbus suburb of Gahanna, Ohio. On May 10, 1968, Sheppard was granted surgical privileges at the Youngstown Osteopathic Hospital,[36] but "[his] skills as a surgeon had deteriorated, and much of the time he was impaired by alcohol".[37] Five days after he was granted privileges, he performed a discectomy on a woman and accidentally cut an artery; the patient died the next day. On August 6, he nicked the right iliac artery on a 29-year-old patient who bled to death internally.[38] Sheppard resigned from the hospital staff a few months later after wrongful death suits had been filed by the patients' families.[39][37]

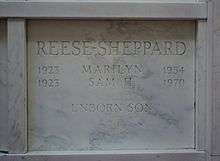

Six months before his death, Sheppard married Colleen Strickland.[40] Towards the end of his life, Sheppard was reportedly drinking "as much as two fifths of liquor a day" (1.5 liters).[41] On April 6, 1970, Sheppard was found dead in his home in Columbus, Ohio.[42] Early reports indicated that Sheppard died of liver failure.[43] The official cause of death was Wernicke encephalopathy (a type of brain damage associated with advanced alcoholism).[44][45] He was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Gardens in Columbus, Ohio.[46] His body remained there until September 1997 when he was exhumed for DNA testing as part of the lawsuit brought by his son to clear his father's name.[47] After the tests, the body was cremated, and the ashes were inurned in a mausoleum at Knollwood Cemetery in Mayfield Heights, Ohio, along with those of his murdered wife, Marilyn.[48]

Civil trial for wrongful imprisonment

Sheppard's son, Samuel Reese Sheppard, has devoted considerable time and effort towards attempting to clear his father's reputation.[49]

In 1999, Alan Davis, a lifelong friend of Sheppard[50] and administrator of his estate, sued the State of Ohio in the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas for Sheppard's wrongful imprisonment.[51]

By order of the court, Marilyn Sheppard's body was exhumed, in part to determine if the fetus she was carrying had been fathered by Sheppard. Terry Gilbert, an attorney retained by the Sheppard family, told the media that "the fetus in this case had previously been autopsied", a fact that had never previously been disclosed. This, Gilbert argued, raised questions about the coroner's office in the original case possibly concealing pertinent evidence.[15] Due to the passage of time and the effect of formaldehyde on the fetus's tissues, paternity could not be established.

Richard Eberling

During the civil trial, plaintiff attorney Terry Gilbert contended that Richard Eberling, an occasional handyman and window washer at the Sheppard home, was the likeliest suspect in Marilyn's murder. Eberling found Marilyn attractive and he was very familiar with the layout of the Sheppard home.[52]

In 1959, detectives were questioning Richard Eberling on various burglaries in the area. Eberling confessed to the burglaries and showed the detectives his loot, which included two rings that belonged to Marilyn Sheppard. Eberling stole the rings in 1958, a few years after the murder, from Sam Sheppard's brother's house, taken from a box marked "Personal Property of Marilyn Sheppard".[53] In subsequent questioning, Eberling admitted his blood was at the crime scene of Marilyn Sheppard. He stated that he cut his finger while washing windows just prior to the murder and bled while on the premises.[54] As part of the investigation, Eberling took a polygraph test with questions about the murder of Marilyn. The polygraph examiner concluded that Eberling did not show deception in his answers, although the polygraph results were evaluated by other experts years later who found that it was either inconclusive or Eberling was deceptive.[55]

In his testimony in the 2000 civil lawsuit, Bailey stated that he rejected Eberling as a suspect in 1966 because "I thought he passed a good polygraph test." When it was presented to Bailey that an independent polygraph expert said Eberling either murdered Marilyn or had knowledge of who did, Bailey stated that he probably would have presented Eberling as a suspect in the 1966 retrial.[56]

DNA evidence, which was not available in the two murder trials, played an important role in the civil trial. DNA analysis of blood at the crime scene showed that there was presence of blood from a third person, other than Marilyn and Dr. Sam Sheppard.[57]

With regard to tying the blood to Eberling, the DNA analysis that was allowed to be admitted to the trial was inconclusive. A plaintiff DNA expert was 90% confident that one of the blood spots belonged to Richard Eberling but, according to the rules of the court, this was not admissible. The defense argued that the blood evidence had been tainted in the years since it was collected, and that an important blood spot on the closet door in Marilyn Sheppard's room potentially included 83% of the adult white population. The defense also pointed out that the results in 1955 from the older blood typing technique, that the blood collected from the closet door was Type O, while Eberling's blood type was Type A.[58]

Throughout his life, Richard Eberling was associated with women who had suspicious deaths and he was convicted of murdering Ethel May Durkin, a wealthy, elderly widow who died without any immediate family. Durkin's 1984 murder in Lakewood, Ohio, was uncovered when a court-appointed review of the woman's estate revealed that Eberling, Durkin's guardian and executor, had failed to execute her final wishes, which included stipulations on her burial.

Durkin's body was exhumed and additional injuries were discovered in the autopsy that did not match Eberling's previous claims of in-house accidents, including a fall down a staircase in her home. In subsequent legal action, both Eberling and his partner, Obie Henderson, were found guilty in Durkin's death. Coincidentally, both of Durkin's sisters, Myrtle Fray and Sarah Belle Farrow, had died under suspicious circumstances as well. Fray was killed after being "savagely" beaten about the head and face and then strangled; Farrow died following a fall down the basement steps in the home she shared with Durkin in 1970, a fall in which she broke both legs and both arms.

Although Eberling denied any criminal involvement in the murder of Marilyn Sheppard,[59] Kathy Wagner Dyal, who worked alongside Eberling in caring for Ethel May Durkin, also testified that Eberling had confessed to her in 1983.[60] A fellow convict also reported that Eberling confessed to the crime. The defense called into question the credibility of both witnesses during the 2000 civil trial. Eberling died in an Ohio prison in 1998, where he was serving a life sentence for the 1984 murder of Ethel May Durkin.

Defense

Steve Dever led the defense trial team for the State of Ohio, which included assistant prosecutors Dean Maynard Boland and Kathleen Martin. They argued that Sheppard was the most logical suspect, and presented expert testimony suggesting that Marilyn Sheppard's murder was a textbook domestic homicide. They argued that Sheppard had not welcomed the news of his wife's pregnancy, he wanted to continue his affairs with Susan Hayes and with other women, and he was concerned about the social stigma that a divorce might create. They claimed the evidence showed that Marilyn Sheppard may have hit Sam Sheppard, sparking an angry rage that resulted in her bludgeoning. Boland evaluated evidence that had been considered by fifty years of investigators, journalists and others, and during the trial he was the first to suggest that the murder weapon used by Sam Sheppard was a bedroom lamp.

The defense asked why Sheppard had not called out for help, why he had neatly folded his jacket on the daybed in which he said he had fallen asleep, and why the family dog, which several witnesses had testified (in the first trial in 1954) was very loud when strangers came to the house, had not barked on the night of the murder (implying that the dog knew the killer).

Verdict

After ten weeks of trial, 76 witnesses, and hundreds of exhibits, the case went to the eight-person civil jury. The jury deliberated just three hours on April 12, 2000, before returning a unanimous verdict that Samuel Reese Sheppard had failed to prove that his father had been wrongfully imprisoned.

Invalidation of wrongful imprisonment claim

On February 22, 2002, the Eighth District Court of Appeals ruled unanimously that the civil case should not have gone to the jury, on the grounds that the statute of limitations had expired, and that a claim for wrongful imprisonment abated with Sam Sheppard's death.[61] In August 2002, the Supreme Court of Ohio declined to review the appeals court's decision.[62][63]

Additional suspect

A 2002 book theorizes that Marilyn Sheppard was murdered by James Call, an Air Force deserter who passed through Cleveland on a multi-state crime spree at the relevant time.[64]

Records from the case

In 2012, William Mason, then Cuyahoga County Prosecutor, designated the Cleveland–Marshall College of Law Library at Cleveland State University as the repository for records and other materials relating to the Sheppard case.[65] The law school has digitized the material, consisting of over 60 boxes of photographs, recordings, and trial exhibits,[65] and posted portions of it online through the school's institutional repository.[66]

In popular culture

In literature

- The 2010 novel Mr. Peanut by Adam Ross features Sam Sheppard as a New York City detective investigating a woman's death and recounting the details of his wife's murder.[67][68]

- Edward D. Hoch created his famous detective Dr. Sam Hawthorne after him.[69]

- The novel Crooked River Burning by Mark Winegardner features the Sheppard murder trial and ends with an epilogue of Sheppard's wrestling days and death.[70]

- Helter Skelter by Vincent Bugliosi with Curt Gentry several times compares the media fanaticism of the Manson Family murders trial to that of the Sheppard case.

- Max Allan Collins's 2020 novel Do No Harm, an entry in his award-winning series of historical crime novels featuring hard-boiled private eye Nate Heller, has Heller investigating the Sheppard case at the behest of both Eliot Ness and Erle Stanley Gardner.

In film

- The 1970 movie The Lawyer is a courtroom drama based on the Sheppard murder trial.

Television

- The television series The Fugitive and the 1993 film of the same name have been cited as being loosely based on Sheppard's story. This claim has always been denied by their creators.[71]

- The TV series American Justice produced an episode based on this case named "The Sam Sheppard Story".

- An episode of the Cold Case television series titled "Schadenfreude" is also based on this case.

- Guilty or Innocent: The Sam Sheppard Murder Case (1975), starring George Peppard, is a television movie about this case.

- The Law & Order television series episode "Justice" is based on Sam Reese Sheppard's mission to clear his father's name.

- My Father's Shadow: The Sam Sheppard Story (1998), starring Peter Strauss, is a television movie about this case.

- The TV series The New Detectives aired an episode about the forensic testing of the evidence in this case, both at the time of Sheppard's indictment and during the later efforts to vindicate him.

- The TV series Notorious produced an episode about this case titled "The Sam Sheppard Story".

- The Nova television series episode "NOVA: The Killer's Trail – The Story of Dr. Sam Sheppard" evaluates the clues and – according to the Product Description that accompanies the DVD version of the episode – comes to a conclusion that "overturn[s] previous assumptions about the killer and point[s] to an entirely new, still unknown, suspect."[72]

- The educational television series Our Living Bill of Rights, produced by Encyclopædia Britannica Films, covers the Sheppard trial in the episode "Free Press vs. Trial By Jury: The Sheppard Case" (also called "Free Press vs Fair Trial By Jury"). The program contains documentary film footage, interviews with Sheppard and Bailey and a dramatization of the activity in the Sheppard home at the time of the murder. The program may be viewed on this site: http://www.historicfilms.com/tapes/15618 (the opening and closing title sequences are omitted, and is entirely in black and white – the original contained some color footage).[73]

- The BBC Four documentary series Catching History's Criminals: The Forensics Story episode (S01E02; 2015) "Traces of Guilt" examined the case, with particular regard to bloodstain evidence and bloodstain pattern analysis.

- The Investigation Discovery series A Crime to Remember details the evidence and Sam Sheppard's story in the Season 3 episode "The Wrong Man", first aired December 15, 2015.

References

- Neff, James (2001). The Wrong Man. New York: Random House.

- "The Dr. Sam Sheppard House Revisited". The Village Newspaper. July 4, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- "History Q & A: Where was the Sam Sheppard house?". The City of Bay Village. 2001. Archived from the original on December 28, 2001.

- Evans, Colin (2003). A Question of Evidence: The Casebook of Great Forensic Controversies, from Napoleon to O. J.. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9780471462682. OCLC 52371365. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- Neff, James (2001). The Wrong Man. New York: Random House. pp. 5–9.

- Butterfield, Fox (March 26, 1996). "After Life of Notoriety and Pain, Son Tries to Solve His Mother's Murder". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- Neff 2001, p. 230

- Neff 2001, p. 85

- The Sam Sheppard Case Archived September 7, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, umd.edu; accessed April 29, 2017.

- "'Wrong Man' makes case for Sheppard's innocence". USA Today. November 8, 2001. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- Neff 2001, pp. 101-02

- Neff 2001, pp. 151-52

- Neff 2001, pp. 166-68

- Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333, 358 (1964) (U.S. Supreme Court)

- "Body of Sam Sheppard's wife exhumed in Ohio". CNN.com. October 5, 1999. Archived from the original on September 19, 2004.

- Affidavit of Paul L. Kirk, filed in the Court of Common Pleas, Criminal Branch, No. 64571

- DeSario, Jack; Mason, William D. (2003). Dr. Sam Sheppard on Trial: The Prosecutors and the Marilyn Sheppard Murder. Kent State University Press. p. 345. ISBN 0-873-38770-8.

- Warnes 2004, p. 252.

- DeSario & Mason 2003, p. 6.

- Tanay 2011, p. 175.

- Warnes 2004, p. 219.

- Perper & Cina 2010, p. 38.

- Neff 2001, p. 193, 218.

- Warnes 2004, p. 220.

- "Sheppard Tragedy Goes On and On". Beatrice Daily Sun. February 18, 1963. p. 2. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- Neff 2001, p. 226-230

- Neff 2001, p. 238

- "The Media and the Trial". Providence.edu. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010.

- Court TV Online – Sheppard Archived May 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Linder, Professor Douglas O. (2017). "Dr. Sam Sheppard Trials: An Account". Famous Trials - UKMC School of Law. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- Andrews, Kenai (August 11, 1969). "People". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- "Osteopath Sam Sheppard Now Wrestling". The News and Courier. August 22, 1969.

- Jonathan Knight (December 1, 2010). Summer of Shadows: A Murder, a Pennant Race, and the Twilight of the Best Location in the Nation. Clerisy Press. ISBN 978-1-57860-468-5.

- Jerry Lawler (December 19, 2002). It's Good to Be the King ... Sometimes. World Wrestling Entertainment. ISBN 978-0-7434-7557-0.

- Sitterson, Aubrey (June 21, 2011). "Wrestling Innovators – The Origins Of Your Favorite Moves". UGO Networks. Archived from the original on February 18, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- "Youngstown Hospital Hires Dr. Sheppard", Pittsburgh Press, April 26, 1968, p5

- James Neff, American Justice: A True Crime Collection (Open Road Media, 2017)

- "'Dr. Sam' Sued In 2nd Death", Pittsburgh Press, September 17, 1968, p46

- "Dr. Sam Sheppard Quits Youngstown Hospital Staff", Akron (OH) Beacon Journal, December 3, 1968, pA10

- "oldschool-wrestling.com". oldschool-wrestling.com.

- Sam and Marilyn Sheppard

- "Dr. Sheppard Is Dead". The Owosso Argus-Press. April 6, 1970. p. 7. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- "Sam Sheppard Died of Natural Causes". Herald-Journal. April 15, 1970. p. 30. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- Neff 2001, p. 366.

- Sheppard, Stephen A. (March 31, 1991). "Sam Sheppard". The Plain Dealer. p. Plain Dealer Magazine 5; Simonich, Milan (September 17, 1997). "Beyond the Grave". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 15. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- "Sam Sheppard's son to talk about exhumation". The Bryan Times. September 16, 1997. p. 8. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- Sam Sheppard's remains exhumed for DNA testing, CNN, September 17, 1997

- "Sheppard's son inters ashes, begins death-penalty march". The Bryan Times. September 19, 1997. p. 2. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- "Seeking the Truth", samreesesheppard.org; accessed April 29, 2017.

- McGunagle, Fred. "The Case of Dr. Samuel Sheppard: Who Killed Marilyn?". CrimeLibrary. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- McGunagle, Fred. "The Case of Dr. Samuel Sheppard: The Third Trial". CrimeLibrary. Retrieved February 16, 2015. After Davis's death in 1999, Charles Murray, who was appointed by the Franklin County Probate Court as the new administrator for the estate, was substituted as plaintiff. Davis v. State, Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Case No. CV96-312322, Plaintiff's Motion for Substitution of Party, February 17, 2000; retrieved February 16, 2015.

- Linder, Douglas O., “Dr. Sam Sheppard Trials”, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law; accessed April 29, 2017.

- Cleveland Police Department, "Plaintiff's Exhibit 0022: Eberling Statement" (1959), Sheppard 2000 Trial Plaintiff's Exhibits. Book 113.

- Tompkins, James R., "Plaintiff's Exhibit 0020: Bay Village Police Report re: Eberling" (1988). Sheppard 2000 Trial Plaintiff's Exhibits. Book 114. http://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/plaintiff_exhibits_2000/114

- Neff 2001, pp. 212, 352

- Neff 2001, pp. 351-52

- Chakarborty, Ranajit, "Chakraborty Report on DNA Typing Involving Richard Eberling, Sam Sheppard, and Marilyn Sheppard" (2000),. Blood Evidence and DNA – Sam Sheppard Case. Book 17.

- Neff 2001, p. 364-367

- Sam Sheppard Case Archived September 17, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, columbusoh.about.com; accessed April 29, 2017.

- Neff 2001, p. 298

- Murray v. State, Cuyahoga App. No. 78374, 2002 Ohio 664 (Feb. 22, 2002). Retrieved Feb. 16, 2015.

- Farkas, Karen (September 28, 2012). "Sam Sheppard's murder case files and exhibits given to Cleveland State University's Cleveland-Marshall College of Law". cleveland.com. Northeast Ohio Media Group. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- Murray v. State, Ohio S. Ct. no. 2002-0626, (Aug. 7, 2002) (docket). Retrieved Feb. 16, 2015.

- Bernard F. Conners, Tailspin, 2002

- Farkas, Karen (September 29, 2012). "Sam Sheppard's murder case files and exhibits given to Cleveland State University's Cleveland-Marshall College of Law". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- "The Same Sheppard Case 1954–2000". Clevland State University. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- Ross, Adam (2010). Mr. Peanut. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-27070-2. OCLC 437298703.

- Minzesheimer, Bob (June 23, 2010). "New voices in literature: Adam Ross". USA Today. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- [Introduction, Diagnosis : Impossible. The Problems of Dr Sam Hawthrone]

- Winegardner, Mark (2001). Crooked river burning. New York: Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15-100294-8. OCLC 44016390.

- Cooper, Cynthia L.; Sam Reese Sheppard (1995). Mockery of justice: the true story of the Sheppard murder case. UPNE. pp. 4, 329. ISBN 978-1-55553-241-3. OCLC 32391248. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- "Amazon.com". March 22, 2005. Retrieved January 7, 2011.

- "Historic Films Stock Footage Archive: F-3122". Historic Films.

Bibliography

- Bailey, F. Lee (1971). The Defense Never Rests. New York: Stein and Day Publishers.

- Cooper, Cynthia; Sheppard, Samuel Reese (1995). Mockery of Justice. Lebanon, N.H.: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1555532411.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- DeSario, Jack P.; Mason, William D. (2003). Dr. Sam Sheppard on Trial: Case Closed. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 0873387708.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holmes, Paul (1961). The Sheppard Murder Case. New York: David McKay Company, Inc.

- Neff, James (2001). The Wrong Man. New York: Random House. ISBN 0679457194.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perper, Joshua A.; Cina, Stephen J. (2010). When Doctors Kill: Who, Why, and How. New York: Copernicus Books. ISBN 9781441913685.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pollack, Jack Harrison (1972). "Dr. Sam: An American Tragedy". Chicago: Henry Regnery Company.

- Seltzer, Louis B. (1956). "The Years Were Good". Cleveland, Ohio: The World Publishing Company.

- Sheppard, Dr. Sam (1966). Endure and Conquer. Cleveland, Ohio: The World Publishing Company.

- Sheppard, Dr. Stephen (1964). My Brother's Keeper. New York: David McKay Company. Inc.

- Tanay, Emanuel (2011). American Legal Injustice: Behind the Scenes With an Expert Witness. Lanham, Md.: Jason Aronson. ISBN 9780765707765.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warnes, Kathy (2004). "The Sam Sheppard Case: Do Three Trials Equal Justice?". In Bailey, Frankie Y.; Chermak, Steven M. (eds.). Famous American Crimes and Trials. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. ISBN 9780275983338.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "The Sam Sheppard Case: 1954–2000". Engaged Scholarship. Cleveland-Marshall College of Law. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- Trials of Sam Sheppard

- Nova: The Killer's Trail Complete transcript of the 1999 Nova program and resources.

- FBI file on Sam Sheppard at vault.fbi.gov

- FBI file on Marilyn Sheppard at vault.fbi.gov