Messapians

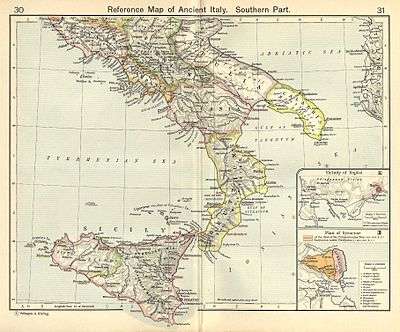

The Messapians (Greek: Μεσσάπιοι, romanized: Messápioi; Latin: Messapii) were a Iapygian tribe that inhabited Salento in classical antiquity. Two other Iapygian tribes, the Peucetians and the Daunians, inhabited central and northern Apulia respectively. All three tribes spoke the Messapian language, but had developed separate archaeological cultures by the seventh century BC. The Messapians lived in the eponymous region Messapia, which extended from Leuca in the southeast to Kailia and Egnatia in the northwest, covering most of the Salento peninsula.[1] This region includes the Province of Lecce and parts of the provinces of Brindisi and Taranto today.

Starting in the third century BC, Greek and Roman writers distinguished the indigenous population of the Salento peninsula differently. According to Strabo, the names Iapygians, Daunians, Peucetians and Messapians were exclusively Greek and not used by the natives, who divided the Salento in two parts. The southern and Ionian part of the peninsula was the territory of the Salentinoi (Greek: Σαλεντῖνοι; Latin: Sallentini), ranging from Otranto to Leuca and from Leuca to Manduria. The northern part on the Adriatic belonged to the Kalabroi (Greek: Καλαβρούς; Latin: Calabri) and extended from Otranto to Egnatia with its hinterland.[2]

After the conquest of the Salento by the Roman Republic in 266 BC[3] the distinction between the Iapygian tribes blurred as they were assimilated into ancient Roman society. Strabo makes it clear that in his time, the end of the first century BC, most people used the names Messapia, Iapygia, Calabria and Salentina interchangeably for the Salento.[4] The name Calabria for the entire peninsula was made official when the Roman emperor Augustus divided Italy in regions and gave the whole region of Apulia the name Regio II Apulia et Calabria.[5] Archaeology still follows the original Greek tripartite division of tribes based on the archaeological evidence.[6]

Etymology

Julius Pokorny derives their ethnonym Messapii from Messapia, interpreted as "(the place) Amid waters", Mess- from Proto-Indo-European and *mes-, "middle" cf. Albanian *medhyo-, "middle" (cf. Ancient Greek μέσος méssos "middle"), and -apia from Proto-Indo-European *ap-, "water" (cf. another toponym, Salapia, "salt water").

History

Origins

_(simple_map).svg.png)

The origin of the Messapii is debated. The most credited theory is that they came from Illyria as one of the Illyrian tribes who settled in Apulia and that they emerged as a sub-tribe distinct from the rest of the Iapyges. It seems that the Iapyges spread northwards from the Salento.[8][9]

The pre-Italic settlement of Gnatia was founded in the fifteenth century BC during the Bronze Age. It was captured and settled by the Iapyges, as they occupied large tracts of territory in Apulia. The Messapii developed a distinct identity from the Iapyges. Rudiae was first settled from the late ninth or early eighth centuries BC. In the late sixth century BC, it developed into a much more important settlement. It flourished under the Messapii, but after their defeat by Rome it dwindled and became a small village. The nearby Lupiae (Lecce) flourished at its expense. The Messapi did not have a centralised form of government. Their towns were independent city-states. They had trade relationships with the Greek cities of Magna Graecia.

Conflict with Taras

In 473 BC, the Greek city of Tarentum (which was on the border with Messapia) and its ally, Rhegion, tried to seize some of the towns of the Messapii and Peucetii. However, the Iapyge tribes defeated them thanks to the superiority of their cavalry.[10] The war against Tarentum continued until 467 BC.

During the Second Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, the Mesapii were allies of Athens. They provided archers for Athens' massive expeditionary force sent to attack Syracuse in Sicily (415–13 BC). The expedition was a disaster and the entire force was destroyed.

In 356 BC, an alliance between Messapii and Lucani led to the conquest of Heraclea and Matapontus. In 342 BC, Tarentum called for the aid of Archidamus III of Sparta. Archidamus died in battle under the walls of the Messapian city of Manduria in 338 BC.[11]

In 333 BC, Tarentum called Alexander I of Epirus to help them in their war with their Lucani. Alexander defeated the Messapii. He died in a battle against the Lucani in 330 BC.[12]

After the campaign of Alexander I, the Messapii switched allegiance. They allied with Tarentum and Cleonymus of Sparta, who campaigned in the region in 303–02 BC to help Tarentum against, again, the Lucani.[13]

Conquest by the Roman Republic

During the Second Samnite War (327–304 BC) between Rome and the Samnites, the Messapii, Iapyges and Peucetii sided with the Samnites. Some of the cities of the Dauni sided with Rome and some of them sided with the Samnites. The city of Canusium went over to the Romans in 318 BC. Silvium, a Peucetii frontier town, was under Samnite control, but it was captured by Rome in 306 BC.

During the Pyrrhic Wars (280–75 BC), the Messapii sided with Tarentum and Pyrrhus the king of Epirus, in Greece[14], who landed at Tarentum, ostensibly to help this city in her conflict with the Romans. According to ancient historians, his aim was to conquer Italy. Pyrrhus fought battles against the Romans and a campaign in Sicily. He had to give up the latter and was defeated by the Romans and left Italy. The Messapii were mentioned by Dionysius of Halicarnassus as fighting for Pyrrhus in the Battle of Asculum.[15]

In 272 BC, the Romans captured Tarentum. In 267 BC, Rome conquered the Messapii and Brundisium.[16][17] This city became Rome's port for sailing to the eastern Mediterranean. Subsequently, the Messapii were rarely mentioned in the historical record. They became Romanised. In 217 BC, Hydra started issuing coins, which often featured Iapagus, the legendary founder of the Iapyges.

During Hannibal's invasion of Italy in the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), the Messapii remained loyal to the Romans. The Battle of Cannae, where Hannibal routed the forces of the Romans and their Italic allies, was fought in the heart of the neighbouring Peucetii territory. The Roman survivors were welcomed into nearby Canusium. Part of the final stages of the war were fought out at Monte Gargano, in the northernmost part of Apulia, in the territory of the Dauni.

Language and writing

The Messapian language is generally considered similar to the Illyrian languages,[18][19][20] although this has been debated as a mostly speculative grouping, as Illyrian languages are themselves poorly attested.[21] Albanian dialects are still a relatable group with Messapian, due to toponyms in Apulia, some of towns that have no etymological forms outside Albanian linguistic sources.[22]

The language became extinct following the Roman conquest of the region,[20] which began during the late 4th century BC.[23] It has been preserved in about 300 inscriptions written in the Greek alphabet and dating from the 6th to the 1st century BC.[19]

Geography

Messapia was relatively urbanized and more densely populated compared to the rest of Iapygia. It possessed 26–28 walled settlements, while the remainder of Iapygia had 30–35 more dispersed walled settlements. The Messapian population has been estimated at 120.000 to 145.000 persons before the Roman conquest.[24]

The main Messapic cities included:

- Alytia (Alezio)

- Brundisium/Brentesion (Brindisi)

- Cavallino

- Hodrum/Idruntum (Otranto)

- Hyria/Orria (Oria)

- Kaìlia (Ceglie Messapica)

- Manduria

- Mesania (Mesagne)

- Neriton (Nardò)

- Rudiae (outside Lecce)

- Mios/Myron (Muro Leccese)

- Thuria Sallentina (Roca Vecchia)

- Uzentum (Ugento)

Other Messapic settlements have been discovered near Francavilla Fontana, San Vito dei Normanni and in Vaste (Poggiardo).

See also

- Ancient Italic peoples

- Messapian pottery

References

- Carpenter, Lynch & Robinson 2014, p. 2, 18 and 38.

- Carpenter, Lynch & Robinson 2014, p. 38–39.

- Carpenter, Lynch & Robinson 2014, p. 46.

- Strabo 1924, 6.3.5.

- Colafemmina 2012, p. 1.

- Carpenter, Lynch & Robinson 2014, p. 40.

- Maggiulli, Sull'origine dei Messapi, 1934; D’Andria, Messapi e Peuceti, 1988; I Messapi, Taranto 1991

- Kathryn Lomas, "Cities, states and ethnic identity in southeast Italy" E. Herring and K. Lomas (eds), The Emergence of State Identities in Italy in the First Millennium BC (London, 2000).

- Talbert, Richard J. A. Atlas of Classical History. Routledge, 1985, ISBN 0-415-03463-9, p. 85. "...from Illyrians, known as Iapyges, who settled first in the heel of Italy and then spread north..."

- Herodotus, The Histories, 7. 170

- Diodoro Siculus, Library of History, 16.63

- Arrian of Nicomedia, The Anabasis of Alexander, 3.6

- Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, 12.4

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The life of Pyrrhus, 13.5–6, 15.4–5

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, 20.1.1–6, 8

- Zonaras, Extracts of History, 8.7

- Florus, Epitome of Roman History, 15

- West 2007, p. 15...To these can be added a larger body of inscriptions from south-east Italy in the Messapic language, which is generally considered to be Illyrian...

- Mallory & Adams 1997, pp. 378f.

- Carpenter, Lynch & Robinson 2014, p. 18.

- Woodard 2008, p. 11...A linking of the two languages, Illyrian and Messapic must however remain a linguistically unverifiable hypothesis..

- Trumper 2018, p. 385: "Overall, the complex of Albanian dialects remains a solid block of the Albanoid group still relatable with Messapic (observed in place naming in Apulia: some towns have no etymon outside Albanoid sources, for example in toponyms such as Manduria)."

- Fronda, Michael P. (2006). "Livy 9.20 and Early Roman Imperialism in Apulia". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 55 (4): 397–417. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4436827.

- Yntema 2008, p. 383.

Sources

- Carpenter, T. H.; Lynch, K. M.; Robinson, E. G. D., eds. (2014). The Italic People of Ancient Apulia: New Evidence from Pottery for Workshops, Markets, and Customs. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139992701.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Colafemmina, Cesare (2012). The Jews in Calabria. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9789004234123.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lamboley, Jean-Luc (2002). "Territoire et société chez les Messapiens". Revue belge de Philologie et d'Histoire. 80 (1): 51–72. doi:10.3406/rbph.2002.4605.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q., eds. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5, (EIEC)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trumper, John (2018). "Some Celto-Albanian isoglosses and their implications". In Grimaldi, Mirko; Lai, Rosangela; Franco, Ludovico; Baldi, Benedetta (eds.). Structuring Variation in Romance Linguistics and Beyond: In Honour of Leonardo M. Savoia. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 385. ISBN 9789027263179.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yntema, Douwe (2008). "Polybius and the Field Survey Evidence of Apulia". In de Ligt, Luuk; Northwood, Simon (eds.). People, Land, and Politics: Demographic Developments and the Transformation of Roman Italy, 300 BC–AD 14. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9789047424499.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- van Dijk, Willemijn. "Tribale tradities en de beleving van het verleden: Messapische cultusplaatsen in de6de tot 3de eeuw voor Christus". In: TMA - Tijdschrift voor Mediterrane Archeologie. jaargang 22, 43 (2010). pp. 8-13.

- D'Andria, Francesco. "Greci ed indigeni in Iapigia". In: Modes de contacts et processus de transformation dans les sociétés anciennes. Actes du colloque de Cortone (24-30 mai 1981) Rome : École Française de Rome, 1983. pp. 287-297. (Publications de l'École française de Rome, 67) [www.persee.fr/doc/efr_0000-0000_1983_act_67_1_2465]

- Lamboley, Jean-Luc. "Les hypogées indigènes apuliens". In: Mélanges de l'École française de Rome. Antiquité, tome 94, n°1. 1982. pp. 91-148. DOI: [www.persee.fr/doc/mefr_0223-5102_1982_num_94_1_1317]

- Lamboley, Jean-Luc. "Territoire et société chez les Messapiens". In: Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire, tome 80, fasc. 1, 2002. Antiquite - Oudheid. pp. 51-72. DOI: ; [www.persee.fr/doc/rbph_0035-0818_2002_num_80_1_4605]

- Mastronuzzi, Giovanni & Ciuchini, Paolo. (2011). "Offerings and rituals in a Messapian holy place: Vaste, Piazza Dante (Puglia, Southern Italy)". In: World Archaeology. 43. 676-701. [DOI: 10.1080/00438243.2011.624773]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Illyria & Illyrians. |