Shakuntala

In Hinduism, Shakuntala (Sanskrit: Śakuntalā) is the wife of Dushyanta and the mother of Emperor Bharata. Her story is told in the Mahabharata and dramatized by many writers, the most famous adaption being Kalidasa's play Abhijñānaśākuntala (The Sign of Shakuntala).[1]Shakuntala's Husband was King Dhushyanta and her son King Bharatha.

| Shakuntala | |

|---|---|

| Mahabharata character | |

| |

| In-universe information | |

| Family | Vishwamitra (father) and Menaka(mother). Kanva (adoptive father) |

| Spouse | Dushyanta |

| Children | Bharata |

Etymology

Rishi Kanva found her in forest as a baby surrounded by Shakunta birds (Sanskrit: शकुन्त, śakunta). Therefore, he named her Shakuntala (Sanskrit: शकुन्तला), meaning Shakunta-protected.[2][3]

In the Adi Parva of Mahabharata, Kanva says:

She was surrounded in the solitude of the wilderness by śakuntas,

therefore, hath she been named by me Shakuntala (Shakunta-protected).

Legend

King Dushyanta first encountered Shakuntala while travelling through the forest with his army. He was pursuing a male deer wounded by his weapon. Shakuntala and Dushyanta fell in love with each other and got married as per Gandharva marriage system. Before returning to his kingdom, Dushyanta gave his personal royal ring to Shakuntala as a symbol of his promise to return and bring her to his palace.[4]

Shakuntala spent much time dreaming of her new husband and was often distracted by her daydreams. One day, a powerful rishi, Durvasa, came to the ashrama but, lost in her thoughts about Dushyanta, Shakuntala failed to greet him properly. Incensed by this slight, the rishi cursed Shakuntala, saying that the person she was dreaming of would forget about her altogether. As he departed in a rage, one of Shakuntala's friends quickly explained to him the reason for her friend's distraction. The rishi, realizing that his extreme wrath was not warranted, modified his curse saying that the person who had forgotten Shakuntala would remember everything again if she showed him a personal token that had been given to her.[1]

Time passed, and Shakuntala, wondering why Dushyanta did not return for her, finally set out for the capital city with her foster father and some of her companions. On the way, they had to cross a river by a canoe ferry and, seduced by the deep blue waters of the river, Shakuntala ran her fingers through the water. Her ring (Dushyanta's ring) slipped off her finger without her realizing it.

Arriving at Dushyanta's court, Shakuntala was hurt and surprised when her husband did not recognize her, nor recollected anything about her.[5] She tried to remind him that she was his wife but without the ring, Dushyanta did not recognize her. Humiliated, she returned to the forests and, collecting her son, settled in a wild part of the forest by herself. Here she spent her days while Bharata, her son, grew older. Surrounded only by wild animals, Bharata grew to be a strong youth and made a sport of opening the mouths of tigers and lions and counting their teeth.[6][7]

Meanwhile, a fisherman was surprised to find a royal ring in the belly of a fish he had caught. Recognizing the royal seal, he took the ring to the palace and, upon seeing his ring, Dushyanta's memories of his lovely bride came rushing back to him. He immediately set out to find her and, arriving at her father's ashram, discovered that she was no longer there. He continued deeper into the forest to find his wife and came upon a surprising scene in the forest: a young boy had pried open the mouth of a lion and was busy counting its teeth. The king greeted the boy, amazed by his boldness and strength, and asked his name. He was surprised when the boy answered that he was Bharata, the son of King Dushyanta. The boy took him to Shakuntala, and thus the family was reunited.[1]

Variants

An alternate narrative is that after Dushyanta failed to recognize Shakuntala, her mother Menaka took Shakuntala to Heaven where she gave birth to Bharata. Dushyanta was required to fight with the devas, from which he emerged victorious; his reward was to be reunited with his wife and son. He had a vision in which he saw a young boy counting the teeth of a lion. His kavach (arm band/armour) had fallen off his arm. Dushyanta was informed by the devas that only Bharata's mother or father could tie it back on his arm. Dushyanta successfully tied it on his arm. The confused Bharata took the king to his mother Shakuntala and told her that this man claimed to be his father. Upon which Shakuntala told Bharata that the king was indeed his father. Thus the family was reunited in Heaven, and they returned to earth to rule for many years before the birth of the Pandava.

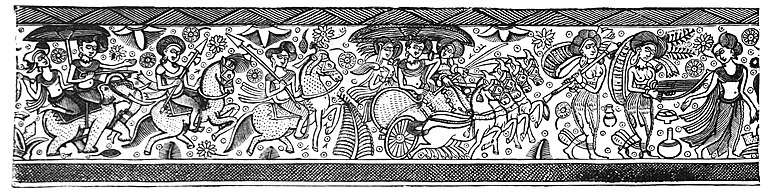

| Ancient renditions of the myth of Shakuntala (2nd century BCE, Sunga period) | |

| |

Adaptations

Theatre, literature and music

Kalidasa

The Recognition of Sakuntala is a Sanskrit play written by Kalidasa.

Opera

Sakuntala is an incomplete opera by Franz Schubert, which originated late 1819 to early 1820. Italian Franco Alfano composed an opera named La leggenda di Sakùntala (The legend of Shakuntala) in its first version (1921) and simply Sakùntala in its second version (1952).

Ballet

- Ernest Reyer (1823–1909) composed a ballet Sacountala on an argument by Théophile Gautier in 1838.

- The Soviet composer Sergey Balasanian (1902–1982) composed a ballet named Shakuntala (premiere 28 December 1963, Riga).[8]

Other literature

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar created a novel in Sadhu Bhasha, Bengali. It was among the first translations from Bengali. Abanindra Nath Tagore later wrote in the Chalit Bhasa (which is a simpler literary variation of Bengali) mainly for children and preteens.

By the 18th century, Western poets were beginning to get acquainted with works of Indian literature and philosophy. The German poet Goethe read Kalidasa's play and has expressed his admiration for the work in the following verses:

Willst du die Blüthe des frühen, die Früchte des späteren Jahres, |

Wouldst thou the young year's blossoms and the fruits of its decline |

| —Goethe, 1791[9] | —translation by Edward Backhouse Eastwick[10] |

In 1808 Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel published a German translation of the Shakuntala story from the Mahabharata.[11]

Film and TV

The earliest adaptation into a film was the Tamil movie Shakuntalai featuring M.S.Subbulakshmi in the role of Shakuntala. Bhupen Hazarika made the Assamese film Shakuntala in 1961. It won the President's Silver Medal and was critically acclaimed. Shakuntala was also made into a Malayalam movie by the same name in 1965. It starred K. R. Vijaya and Prem Nazeer as Shakuntala and Dushyanta respectively. Rajyam Pictures of C. Lakshmi Rajyam and K. Sridhar Rao produced a Shakuntala film in 1966 starring N. T. Rama Rao as Dushyanta and B. Saroja Devi as Shakuntala. It is directed by Kamalakara Kameswara Rao.[12] V. Shantaram also made a Hindi film titled 'STREE' on this story. On the Marathi stage there was a musical drama titled Shakuntal on the same story.

Art

Camille Claudel created a sculpture Shakuntala.[13]

References

- "Shakuntala - the Epitome of Beauty, Patience and Virtue". Dolls of India. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "The Mahabharata, Book 1: Adi Parva: Sambhava Parva: Section LXXII". www.sacred-texts.com.

- "The Mahabharata in Sanskrit: Book 1: Chapter 66". www.sacred-texts.com.

- Miller, Barbara Stoler (1984). Theater of Memory: The Plays of Kalidasa. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 122.

- Glass, Andrew (June 2010). "Vasudeva, Somadeva (Ed. and Tr.), The Recognition of Shakúntala by Kālidāsa Olivelle, Patrick (Ed. and Tr.), The Five Discourses on Worldly Wisdom by Visnuśarman Mallinson, Sir James (Ed. and Tr.), The Emperor of the Sorcerers..." Indo-Iranian Journal. doi:10.1163/001972409X12645171001532.

- Kalidasa (2000). Shakuntala Recognized. Translated by G.N. Reddy. Victoria, BC, Canada: iUniverse. ISBN 0595139809.

- Yousaf, Ghulam-Sarwar (2005). "RELIGIOUS AND SPIRITUAL VALUES IN KALIDASA'S SHAKUNTALA". Katha. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Hakobian, Levon (25 November 2016). Music of the Soviet Era: 1917–1991. Taylor & Francis. p. 387. ISBN 9781317091875. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Goethe - Gedichte: Sakontala". www.textlog.de.

- Pratap, Alka (2 February 2016). "Hinduism's Influence on Indian Poetry".

- Figueira 1991, pp. 19–20

- Shakuntala on IMDb

- "CAMILLE CLAUDEL FROM 1 OCTOBER TO 5 JANUARY CAMILLE CLAUDEL COMES OUT OF THE RESERVE COLLECTIONS". Musée Rodin. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

Sources

- Dorothy Matilda Figueira. Translating the Orient: The Reception of Sakuntala in Nineteenth-Century Europe. SUNY Press, 1991. ISBN 0791403270

- Romila Thapar. Sakuntala: Texts, Readings, Histories. Columbia University Press, 2011. ISBN 0231156553

- Vyasa. Mahabharata.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shakuntala. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Shakuntala |