Sack of Palermo

The Sack of Palermo is the popular term for the construction boom from the 1950s through the mid-1980s that led to the destruction of the green belt and villas that gave Palermo, Italy, architectural grace, to make way for characterless and shoddily constructed apartment blocks. In the meantime Palermo's historical centre, severely damaged by Allied bombing raids in 1943, was allowed to crumble. The bombing condemned nearly 150,000 to live in crowded slums, shantytowns, and even caves.[1]

Background

Between 1951 and 1961 the population of Palermo had risen by 100,000, caused by a rapid urbanisation of Sicily after World War II as land reform and mechanisation of agriculture created a massive peasant exodus and rural landlords moved their investment into urban real estate. This led to an unregulated and undercapitalised construction boom from the 1950s through the mid-1980s that was characterised by an aggressive involvement of mafiosi in real estate speculation and construction. The years 1957 to 1963 were the high point in private construction, followed in the 1970s and 1980s by a greater emphasis on public works. From a citizenry of 503,000 in 1951, Palermo grew to 709,000 in 1981, an increase of 41 percent.[1]

More serious than the wartime destruction of the old city was the political decision to turn away from its restoration in favour of building a “new Palermo”, at first concentrated at the northern end, beyond the Art Nouveau neighbourhood of 19th century expansion. Subsequently, in other zones to the west and the south spreading over, and obliterating, the Conca d'Oro orchards, villas, and hamlets, accelerating the cementification of what had been green.[1]

Real estate developers ran wild, pushing the centre of the city out along Viale della Liberta toward the new airport at Punta Raisi. With hastily drafted zoning variances or in wanton violation of the law, builders tore down countless Art Nouveau palaces and asphalted many of the city's finest parks, transforming one of the most beautiful cities in Europe into a thick, unsightly forest of cement condominia. Villa Deliella, one of the most important buildings of the great Sicilian architect Ernesto Basile was razed to the ground in the middle of the night, hours before it would have come under protection of the historic preservation laws.[2]

Mafia involvement

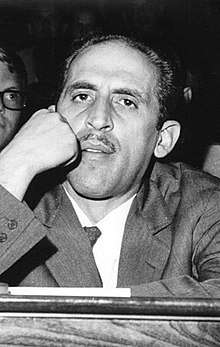

The high point of the sack happened when the Christian Democrat Salvo Lima was mayor of Palermo (1958-1963 and 1965-1968) and Vito Ciancimino assessor for public works.[3] They supported Mafia-allied building contractors such as Palermo's leading construction entrepreneur Francesco Vassallo – a former cart driver hauling sand and stone in a poor district of Palermo. Vassallo was connected to mafiosi like Angelo La Barbera and Tommaso Buscetta. In five years, over 4,000 building licences were signed, some 2,500 in the names of three pensioners who had no connection with construction at all.[2][4]

Developers with close Mafia ties were not afraid to use strong-arm tactics to intimidate owners into selling or to clear the way for their projects.[2] The Parliamentary Antimafia Commission noted:

- It was in Palermo in particular that the phenomenon [of illegal construction] took on dimensions such as not to leave any doubts about the insidious penetration by the Mafia of public administration. The administrative management of Palermo City Council reached unprecedented heights of deliberate non-observation of the law around 1960.[5]

References

- Schneider & Schneider (2003). Reversible Destiny, p. 14-19

- Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 21-22

- Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 277-288

- Servadio, Mafioso, p. 204-06

- Antimafia Commission Final Majority Report 1976, p. 54, quoted in: Jamieson, The Antimafia, p. 21

- Dickie, John (2004). Cosa Nostra. A history of the Sicilian Mafia, London: Coronet, ISBN 0-340-82435-2

- Jamieson, Alison (2000), The Antimafia. Italy’s Fight Against Organized Crime, London: MacMillan Press ISBN 0-333-80158-X

- Schneider, Jane T. & Peter T. Schneider (2003). Reversible Destiny: Mafia, Antimafia, and the Struggle for Palermo, Berkeley: University of California Press ISBN 0-520-23609-2

- Servadio, Gaia (1976), Mafioso. A history of the Mafia from its origins to the present day, London: Secker & Warburg ISBN 0-436-44700-2

- Stille, Alexander (1995). Excellent Cadavers. The Mafia and the Death of the First Italian Republic, New York: Vintage ISBN 0-09-959491-9