Russia Row

Russia Row is a street in the City of London that runs between Milk Street and Trump Street on the northern side of the former Honey Lane Market. Russia Court, formerly Robin Hood Court, the home of the Russia Company, was once located on the northern side of the street and the City of London School on the south side. The street is thought to have received its name around 1804, shortly before Russia decided to enter the Napoleonic Wars on the same side as Britain. It was damaged by German bombing during the Second World War and has since been completely rebuilt.

Location

Russia Row is located in the City of London and runs between Milk Street in the west and Trump Street in the east.[1]

Origins

Russia Row was built on land that was formerly on the north side of Honey Lane Market,[2] itself partially on the former site of the parish church, All Hallows Honey Lane, which was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and not rebuilt.[3] It fell within Cheap Ward and Cripplegate Ward Within.[2]

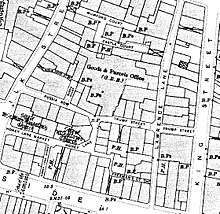

Archaeological investigations of a site on the corner of the modern Milk Street and Russia Row by the Museum of London in 1976-7 confirmed documentary sources in suggesting that Russia Row had no medieval predecessor, the site being entirely taken up with buildings before the fire. Roman remains were found including the location of a Roman street that ran roughly north–south under what is now Russia Row.[4]

Russia Row is joined to Milk Street at its eastern end and also once by Robin Hood Alley which has also been called Robinson's Court, Robin Hood Court and Robin Court.[5] The southern end of the alley was known as Russia Court when the offices of the Russia Company (chartered 1555) were located there.[6]

Henry Harben writes that the street was first recorded in Lockie's Topography of London in 1810.[2] It is not mentioned, however, on Richard Horwood's 1799 or 1813 maps.[7] Gillian Bebbington dates the street to 1804, the year before Russia decided to enter the Napoleonic Wars on Britain's side[8] and The London Encyclopaedia also connects it to Russia's involvement in the war.[9] It is mentioned in The Times in 1804, in pages extracted from The London Gazette, as the address of T. Pierson and W. Samnion, factors paying dividends in that year.[10]

Later history

The street has always been primarily commercial. The hosiery manufacturers I. & R. Morley of Nottingham opened a warehouse in Russia Row as part of their expansion to the City of London, later moving to nearby Wood Street and also having premises in adjacent Milk Street and Gresham Street.[13] In 1852 probate was granted for the will of James Gilburt, a silk manufacturer of No 4 Russia Row.[14] In 1853 it was reported in The London Gazette that the warehouseman William Henry Porter of "Russia-row" had been granted a patent in 1838 for "improvements in anchors", and that Mary Honiball of St John's Wood was disputing this patent, alleging that Porter had not been the first inventor.[15]

In 1835, the City of London School was built on the south side of the street facing Milk Street, on the site of the former Honey Lane Market.[16] It was paid for with money bequeathed for the purpose by John Carpenter, city clerk in the reign of King Henry V.[6] It grew so rapidly that in 1883 it moved to larger premises at the Victoria Embankment.[17]

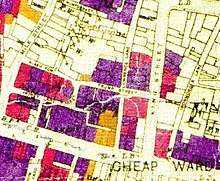

The area north of Cheapside was seriously damaged by Nazi bombing on 29 December 1940 during the Second World War.[12][18] Russia Row has since been completely rebuilt with office buildings and some retail premises at street level. The north side is an office building of 386,000 square feet (35,900 m2)[19] known as 30 Gresham Street that continues along Trump Street and was developed by Land Securities in 2002–03. It was described at the time as "the biggest speculative office development in the capital".[20]

References

- Ordnance Survey map, Digimap. Retrieved 2 February 2018. (subscription required)

- "Russia Row - Ryole (la) - British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus and Bradley, Simon (2002). The Buildings of England London 1: The City of London. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. p. 557. ISBN 9780300096248.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Schofield, John, et al "Medieval buildings and property development in the area of Cheapside" Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, Vol. 41 (1990), pp. 39-237.

- Robin Hood Court.- - Rolls' Yard. British History Online. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Russia Court" in Al Smith (1970) Dictionary of City of London Street Names. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. p. 172. ISBN 0715348809

- Laxton, Paul & Joseph Wisdom. (1985) The A to Z of Regency London. London: London Topographical Society. pp. 30-31. ISBN 0902087193

- "Russia Row" in Gillian Bebbington (1972) London Street Names. London: B.T. Batsford. p. 281. ISBN 0713401400

- "Russia Row" in Christopher Hibbert; Ben Weinreb; John Keay; Julia Keay. (2008). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). London: Pan Macmillan. p. 738. ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "From the London Gazette, August 7, 1804", The Times, 8 August 1804, p. 2.

- Ordnance Survey map of London, 1916, 2nd revision. Digimap. Retrieved 10 January 2018. (subscription required)

- The meticulously hand-coloured bomb damage maps of London – in pictures. The Guardian, 2 September 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- I. & R. Morley, Nottingham. Nottinghamshire History. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Will of James Gilburt, Silk Manufacturer of No 4 Russia Row , City of London. The National Archives. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- "In the matter of letters patent...", The London Gazette, 1854, p. 2338.

- "Honey Lane Market" in Hibbert et al, The London Encyclopaedia, p. 413.

- "City of London School" in Hibbert et al, The London Encyclopaedia, pp. 187-188.

- Smith, p. 139.

- "Buildings going up despite City glut", Jenny Davey, The Times, 20 October 2003, p. 25.

- "Gamble on Gresham St." The Times, 22 May 2003, p. 35.

External links

![]()