Rusinga Island

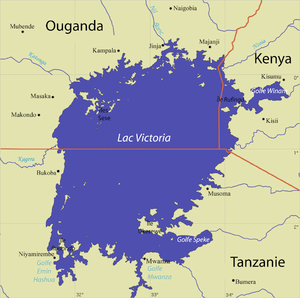

Rusinga Island, with an elongated shape approximately 10 miles (16 km) from end to end and 3 miles (5 km) at its widest point, lies in the eastern part of Lake Victoria at the mouth of the Winam Gulf. Part of Kenya, it is linked to Mbita Point on the mainland by a causeway.[1]

Demography

The local language is Luo, although the ancestors of the current inhabitants were Suba people who came in boats several hundred years ago from Uganda as refugees from a dynastic war. Many Rusinga place names portray Suba[2] origins, including the island's name itself and its central peak, Lunene. There was an extinct language of Uganda called Singa, alternatives Lusinga and Lisinga, spoken only on Rusinga Island (which, of course is in Kenya). It belonged to the same group of Niger–Congo as Suba.[3] As of 2006, estimates of Rusinga's population range between 20,000 and 30,000. The entire island is part of the Homa Bay County.

Most residents of Rusinga make their living from subsistence agriculture (maize and millet), as well as fishing. The native tilapia is still caught, though this species (like all others native to the lake) has been decimated by the voracious Nile perch that was introduced into the lake in 1954. Constant onshore winds cool the lakeward side of the island and provide clean beaches with ideal swimming and boating conditions, but poor roads between Rusinga and the nearest town, Homa Bay, inhibit trade and tourism. The brightly glittering black sands of the beaches are made of crystals of melanite garnet, barkevikite hornblende, and magnetite eroded from the uncompahgrite lava fragments in the agglomerates that overlie the fossil beds.

The island is also notable as the family home and burial site of Tom Mboya, who before his assassination in 1969 was widely pegged as Jomo Kenyatta's successor as President of the new nation of Kenya.

Palaeontology

Rusinga is widely known for its extraordinarily rich and important fossil beds of extinct Miocene mammals, dated to 18 million years.[4] The island had been only cursorily explored until the Leakey expedition of 1947-1948 began systematic searches and excavations, which have continued sporadically since then. The end of 1948 saw the collection of about 15,000 fossils from the Miocene, including 64 primates called by Louis Leakey "Miocene apes."

All the species of Proconsul were among the 64 and all were given the name africanus, although many were reclassified into nyanzae, major and heseloni later. Mary Leakey discovered the first complete skull of Proconsul, then considered a "stem hominoid", in 1948. Excavation of the fossil was completed by Louis' native assistant, Heselon Mukiri (whence Walker's 1993 name heseloni). Many thousands of fossils are now known from five major sites, with abundant hominoids including an almost complete skeleton of a second species of Proconsul, as well as Nyanzapithecus, Limnopithecus, Dendropithecus and Micropithecus,[5] all of which show arboreal rather than terrestrial adaptations. The first true monkeys do not appear until around 15 million years ago, so it is widely supposed that the diverse Early Miocene African catarrhines like those found on Rusinga filled that adaptive niche. The phylogenetic position of these primates has been debated. It has been theorized that Proconsul is a stem catarrhine and therefore ancestral to both Cercopithecids (Old World monkeys) and hominids (great apes and humans), rather than a stem hominoid.[6]

Pleistocene mammal fossils, including an extinct antelope called Rusingoryx, notable for its nasal dome hypothesised to produce loud calls, known nowhere else, are also common in former shoreline deposits around the edges of the island, left behind as Lake Victoria has slowly subsided over the centuries due to erosion in its outlet.

Geology

The fossil beds are layers of volcanic ash produced by a succession of explosive eruptions during the earliest stages of a volcano that eventually covered an area 75 miles in diameter. The volcano is now eroded down to the frozen magma in its vent that makes up the Kisingiri hills on the mainland opposite Rusinga, and the surrounding remnants of the cone: the semicircular Rangwa mountain range, and the islands of Rusinga and neighboring Mfangano Island. This rift valley volcano on the southern flank of the now-inactive Winam Gulf tapped much deeper in the mantle than oceanic or subduction zone volcanos, and its lavas and explosive ash clouds thus contained much more carbonate and alkali than normal. This meant that even though the Miocene environment was a tropical rainforest, the chemistry of the successive ash beds was that of a desert dry lake, preserving everything from caterpillars and berries to apes and elephants in an unusual situation found only in a few other East African volcanos, notably Menengai and Homa Mountain in western Kenya, Napak and Mount Elgon in Uganda, and the much younger Ol Doinyo Lengai in Tanzania, which created the fossil beds of Olduvai Gorge.

See also

- Lake Victoria

- Louis Leakey

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- Rusinga Cultural Festival

Notes

- The Google clickable map can be found at and a road map can be found at . A district map is at

- See Suba at the ethnologue.com website.

- See Singa at the ethnologue.com website.

- For a Potassium-Argon determination of the date refer to Miocene Stratigraphy and Age Determinations, Rusinga Island, Kenya, article by J. A. VAN COUVERING & J. A. MILLER in Nature 221, 628 - 632 (15 February 1969). The abstract and bibliography are displayed no charge.

- A University College London research article discussing finds of these fossil apes at Koru and elsewhere, including Rusinga, can be found at New Finds of Small Fossil Apes from the Miocene Locality at Koru in Kenya by T. Harrison. The article is displayed at the nyu.edu site, no charge.

- , Harrison T. 1987. "The phylogenetic relationships of the early catarrhine primates: a review of the current evidence." Journal of Human Evolution 16(1), 41-80

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Rusinga Island. |

- GEF RUSINGA ISLAND Projects, United Nations Development Programmes.

- Greening Rusinga Island, Africa Now site.

- Palaeoenvironments of Early Miocene Kisingiri volcano Proconsul sites: Evidence from carbon isotopes, palaeosols and hydromagmatic deposits, article by Erick Bestland and Evelyn Krull, Journal of the Geological Society, September, 1999. An extensive abstract of this highly technical article is displayed at no charge.

- Living Waters Intl, Since 2006, Living Waters Intl, a faith based non-profit organization, has been providing clean water, medical care, a feeding center, orphan assistance and educational facility upgrades, sustainable vegetable gardens, to the people of Rusinga Island, Kenya, Africa