Rumi ghazal 163

Rumi's ghazal 163, which begins Beravīd, ey harīfān "Go, my friends", is a well known Persian ghazal (love poem) of seven verses by the 13th-century poet Jalal-ed-Din Rumi (usually known in Iran as Mowlavi or Mowlana). The poem is said to have been written by Rumi about the year 1247 to persuade his friend Shams-e Tabriz to come back to Konya from Damascus.

In the poem Rumi asks his friends to fetch his beloved friend back home, and not accept any excuses. In the second half he praises his beloved and describes his marvellous qualities. He finishes by sending his greetings and offers his service.

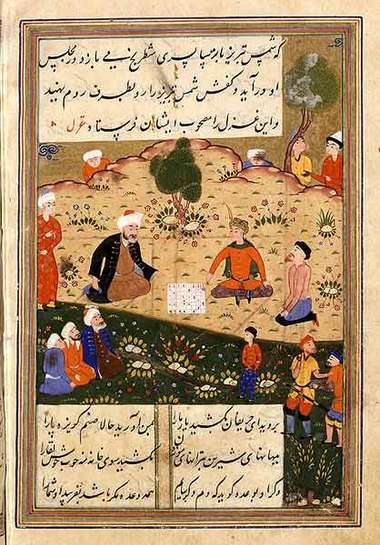

The poem is popular in Persian-speaking countries and has been set to music by a number of musicians including the Afghan singers Hangama and Ahmad Zahir. It is also famous for a miniature painting of 1503 containing three of the verses and illustrated with a picture of Shams-e Tabriz playing chess.

The situation

Around 1226 Jalal-ed-Din Rumi, aged 19, settled with his father at Konya (ancient Iconium), the capital of the Seljuq prince Ala-od-Din Keykobad. On his father's death in 1231, Jalal-ed-Din took over his duties as religious teacher and had a large following of students. It was in 1244 that a certain dervish, a man of great spiritual enthusiasm, Shams-e Tabriz, came to Konya. Jalal-ed-Din was so smitten by Shams that "for a time he was thought insane". However, Shams became unpopular with Rumi's followers and after a year and a half he was forced to leave Konya. Hearing that Shams was in Damascus, Rumi sent his eldest son Sultan Walad there to persuade Shams to return, taking this poem with him. Shams was persuaded to return to Konya, but shortly afterwards he disappeared and it is presumed that he was murdered. At the time of this poem, Rumi was about 40 years old, and Shams was 62.[1][2] Since Rumi was married in 623 A.H. (about 1226),[3] Sultan Walad was about 20 years old.

The Persian miniature

The Persian miniature illustrated here was painted in c. 1503, some 250 years after the event depicted. In the upper half are these introductory words explaining the origin of the poem:

- که شمس تبریز با ترسا پسری شطرنج مے بازد در مجلس

- او در آید و کفش شمس تبریز را رو بطرف روم نهید

- و این قزل را مصحوب ایشان فرستاد

- ke Šams-e Tabrīz bā tarsā pesar-ī šatranj mī[4] bāzad dar majles-e ū dar-āyad va kafš-e Šams-e Tabrīz rā rū be taraf-e Rūm nehīd va īn qazal rā mashūb-e īšān ferestād.

- "When Shams-e Tabriz was playing chess with a Christian boy, he (Sultan Walad) came upon the place where he was sitting and persuaded him to return to Konya (literally, turned Shams-e Tabriz's shoe in the direction of Rūm), and he (Rumi) sent this ghazal referring to him (Shams)."

In the lower half of the painting are the first three verses of ghazal 163.

As is often the case in miniature paintings, the same persons are represented more than once.[5] The painting is divided into three sections. At the top Sultan Walad (top right) and a companion are seen arriving; two beardless young men, one dressed in red, the other in blue, who can be seen later to be followers or disciples of Shams, are with them, presumably guiding them to the spot. In the central panel, Shams is seen playing chess with the Christian boy, watched by the young man in the red gown on the left and by Sultan Walad on the right. (The young man appears to have on a damask gown, appropriate to someone from Damascus.) In the lowest panel, which shows the scene at night, the men in red and blue gowns are seated next to Shams (the man in red now has a beard but is probably the same man), while Sultan Walad and his companion, dressed in clothes suitable for travel, are on the right. The companion is carrying a sword and is presumably a bodyguard to protect Sultan Walad on the journey.

The type of chess depicted in the painting, called shatranj, was similar to modern chess, but with different rules. (See Shatranj.)

The poem

The transcription below represents the pronunciation used today in Iran. The sound خ (as in Khayyam) is written x, and ' is a glottal stop. It is probable, however, that the Afghan pronunciation (see External links below), in which a distinction is made between ī and ē, ū and ō, and gh and q, and final -e is pronounced -a, is closer to the pronunciation of medieval times used by Rumi himself. (See Persian phonology.)

Overlong syllables, which take the place of a long and short syllable in the metre, are underlined.

- 1

- بروید ای حریفان بکشید یار ما را

- به من آورید آخر صنم گریزپا را

- beravīd 'ey harīfān * bekešīd yār-e mā rā

- be man āvarīd 'āxer * sanam-ē gorīz-pā rā

- Go friends, fetch our beloved;

- bring me please that fugitive idol!

- 2

- به ترانههای شیرین به بهانههای زرین

- بکشید سوی خانه مه خوب خوش لقا را

- be tarānehā-ye šīrīn * be bahānehā-ye zarrīn

- bekešīd sū-ye xānē * mah-e xūb-e xoš-leqā rā

- With sweet songs and golden excuses,

- fetch home the beautiful-faced good moon.

- 3

- وگر او به وعده گوید که دمی دگر بیایم

- همه وعده مکر باشد بفریبد او شما را

- v-agar ū be va'de gūyad * ke dam-ī degar biyāyam

- hame va'de makr bāšad * befirībad ū šomā rā

- And if he promises that "I will come another time",

- every promise is a trick, he will cheat you.

- 4

- دم سخت گرم دارد که به جادوی و افسون

- بزند گره بر آب او و ببندد او هوا را

- dam-e saxt garm dārad * ke be jādov-ī o afsūn

- bezanad gereh bar āb ū * va bebandad ū havā rā

- He has such warm breath, that with magic and enchantments

- he can tie a knot in water and make air solid.

- 5

- به مبارکی و شادی چو نگار من درآید

- بنشین نظاره میکن تو عجایب خدا را

- be mobārakī o šādī * čo negār-e man dar āyad

- benešīn nazāre mīkon * to 'ajā'eb-ē Xodā rā

- With blessedness and joy, when my beloved appears,

- sit and keep gazing on the miracles of God.

- 6

- چو جمال او بتابد چه بود جمال خوبان

- که رخ چو آفتابش بکشد چراغها را

- čo jamāl-e ū betābad * če bovad jamāl-e xūbān?

- ke rox-ē čo āftāb-aš * bekošad cerāqhā rā

- When his glory shines, what is the glory of the beautiful?

- Since his sun-like face kills the lamps.

- 7

- برو ای دل سبک رو به یمن به دلبر من

- برسان سلام و خدمت تو عقیق بیبها را

- borow ey del-ē sabok-row * be Yaman be delbar-ē man

- berasān salām o xedmat * to 'aqīq-e bī-bahā rā

- Go, o lightly-moving heart, to Yemen, to the stealer of my heart;

- take my greetings and my service to that jewel without price.

Metre

The metre is known as bahr-e ramal-e maškūl.[6] In Elwell-Sutton's system it is classified as 5.3.8(2).[7] It is a doubled metre, with each line consisting of two identical eight-syllable sections divided by a break:

- | u u – u – u – – || u u – u – u – – |

This rhythm is identical with the Anacreontic metre of Ancient Greek poetry, named after the poet Anacreon (6th/5th century BC) from Asia Minor.

References

- Nicholson, R. A. Selected Poems from the Divani Shamsi Tabriz. pp. xvi–xxiii.

- Mojaddedi, Jawid (2004). Jalal al-Din Rumi: The Masnavi Book 1. (Oxford). pp. xv–xvii.

- Nicholson, R. A. Selected Poems from the Divani Shamsi Tabriz. pp. xvii.

- The backwards pointing tail of the letter ye represents the sound ē found in medieval Persian and still today in the Urdu alphabet.

- For another example, see Naqdhā rā bovad āyā.

- Thiesen, F. (1982). A Manual of Classical Persian Prosody, p. 161.

- Elwell-Sutton, L. P. (1976). The Persian Metres, p. 137.

External links

- Ghazal 163. Text and notes (Ganjoor).

- Recitation (Iranian pronunciation)

- Recitation (Iranian pronunciation, female speaker)

- Recitation by Abdolkarim Soroush

- Ghazal 163 sung by the Afghan singer Hangāma (Afghan pronunciation)

- Ghazal 163 sung by Afghan singer Ahmad Zahir. (Afghan pronunciation)

- Ghazal 163 sung by female singer