Rotunda radicals

The Rotunda radicals were a diverse group of London radical reformers who gathered around the Blackfriars Rotunda after 1830.

Terminology

They were known at the time as Rotundists or Rotundanists. The Rotundists were identified by one historian as the followers of William Lovett.[1] Lovett belonged to the Radical Reform Association which in the summer of 1830 was holding weekly meetings at the Rotunda.[2] Graham Wallas, however, stated that "Rotundanist" was used for the membership of the National Union of the Working Classes (NUWC);[3] the Rotunda was an organising venue for Henry Hetherington and James Watson in running the NUWC.[4]

Uses of the Rotunda

In May or June 1830 Richard Carlile took over the Rotunda, and it became a centre for radical lectures and meetings. Carlile borrowed £1275 to renovate and lease the place, backed by William Devonshire Saull and Julian Hibbert.[5] Lectures then continued in the room where Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Hazlitt had spoken when the Surrey Institution was housed in the Rotunda, with a capacity of about 500.[6] Carlile lectured and Robert Taylor preached there, with invited speakers.[7]

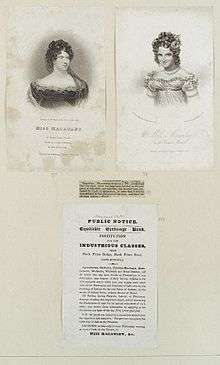

Henry Hunt presented a petition to Parliament on 5 September 1831, with signatures from a Rotunda meeting; it asked for "the Liberation of those Imprisoned for selling cheap Publications in the Streets".[8] John Gale Jones spoke there in 1830–1,[9] Zion Ward in 1831.[10] Eliza Sharples started her speaking career there in 1832.[11] There were also waxworks and wild beasts.[12]

James Elishama Smith gave his Lecture on a Christian Community at the Rotunda, as the headquarters of the National Union of the Working Classes,[13] in 1833; Carlile had given up the lease in 1832.[14] From 1833 it had a period called the Globe Theatre.[12]

References

- Christina Parolin (2010), Radical Spaces: Venues of popular politics in London, 1790–c. 1845; Google Books.

Notes

- Clement Boulton Roylance Kent, The English Radicals; an historical sketch (1899), p. 310; archive.org.

- Goodway, David. "Lovett, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17068. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Graham Wallas, The Life of Francis Place 1771 to 1854 (1908, 2004 reprint), p. 272; Google Books.

- Iain McCalman, Radical Underworld: prophets, revolutionaries, and pornographers in London, 1795-1840 (1986), p. 231; Google Books.

- Parolin, p. 200; Google Books.

- Richard W. Davis, Richard J. Helmstadter (editors), Religion and Irreligion in Victorian Society: essays in honor of R. K. Webb (1992), pp. 51–2; Google Books.

- Martin, Philip W. "Carlile, Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4685. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hansard, Minutes, HC Deb 05 September 1831 vol 6 cc1131-2.

- Parolin, p. 3; Google Books.

- Stunt, Timothy C. F. "Ward, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28693. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Royle, Edward. "Carlile, Elizabeth Sharples". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38370. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- British History Online, Old and New London: Volume 6 by Edward Walford (1878) pp. 368-383.

- Stunt, Timothy C. F. "Smith, James Elishama". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25826. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Davis and Helmstadter, p. 60; Google Books.