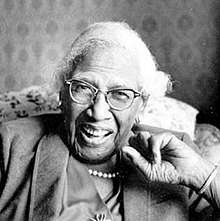

Rosina Tucker

Rosina Tucker (1881–1987) was an American labor organizer, civil rights activist, and educator. She is best known for helping to organize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first African-American trade union. At the age of one hundred, Tucker narrated an award-winning documentary about the union, Miles of Smiles, Years of Struggle.

Rosina Tucker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Rosina Budd Harvey 4 November 1881 Northwest, Washington, D.C. |

| Died | 3 March 1987 (aged 105) |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Rosina Corrothers |

| Occupation | labor organizer, civil rights activist, educator |

| Spouse(s) | James D. Corrothers Berthea J. Tucker |

Early life

Rosina Budd Harvey was born in Northwest Washington, D.C., on November 4, 1881. She was one of nine children of Lee Roy and Henrietta Harvey, both former slaves from Virginia. Her father, who worked as a shoemaker, taught himself to read and write and fostered a love of books in his children. In 1897 Rosina Harvey was visiting an aunt in Yonkers, New York, when she met the poet James D. Corrothers, who was a guest minister there. She married Corrothers on December 2, 1899. The couple had a son, Henry Harvey Corrothers, and raised Corrothers' other son from a previous marriage. Following the death of her husband in 1917, she moved back to Washington, D.C., where she worked for the federal government as a file clerk. She married Berthea "B.J." Tucker, a Pullman porter, on November 27, 1918.[1]

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

The porters' union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, launched in 1925 with A. Philip Randolph as president. B.J. Tucker joined immediately, and he and Rosina began organizing in Washington. The porters worked long hours, and had little time for union activities. Many also feared that they would lose their jobs if their employers learned of their union involvement. For this reason, the porters' wives did much of the organizing, often holding meetings in secret. Rosina Tucker attended several secret meetings with A. Philip Randolph and other union leaders. On behalf of the union she visited some 300 porters at their homes in the Washington area, distributing literature, recruiting members, and collecting dues. She also organized the local Ladies' Auxiliary, which raised funds for the union by hosting dances, dinners, and the like. When the Pullman Company learned of Rosina Tucker's union activities, they fired her husband in retaliation. After Tucker confronted her husband's supervisor at his office, her husband was rehired. Tucker described the scene later:[1]

I looked him right in the eye and banged on his desk and told him I was not employed by the Pullman company and that my husband had nothing to do with any activity I was engaged in ... I said, 'I want you to take care of this situation or I will be back.' He must have been afraid ... because a black woman didn't speak to a white man in this manner. My husband was put back on his run.[2]

In 1938 she attended the national union conference in Chicago, where she chaired the Constitution and Rules committee. That year she was elected secretary-treasurer of the union's auxiliary, a position she held for over 30 years.[2] In 1941 she helped organize the union's first March on Washington, which was called off when President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802. She later helped organize the March on Washington of 1963.[1]

Later years

Rosina Tucker continued her union and civil rights activities for many years. She helped organize laundry workers, teachers, and red caps in the Washington area.[2] She lobbied Congress for labor and education legislation and testified before House and Senate committees on day care, education, labor, and D.C. voting rights. At the age of 102, she testified before a Senate subcommittee on aging; at 104, she was still traveling the country giving lectures. She also wrote an autobiography, My Life as I Have Lived It, which was published posthumously in 2012.[1]

Tucker narrated a 1982 documentary film about the union, Miles of Smiles, Years of Struggle. Produced by Jack Santino and Paul Wagner, the film has won numerous awards, including four regional Emmys and a CINE Golden Eagle.[3]

She was 105 years old when she died on March 3, 1987.[1]

Publications

- Ruffin, C. Bernard, ed. (2012). My Life as I Have Lived It: The Autobiography of Rosina Corrothers-Tucker, 1881-1987. Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0788453649.

- Chateauvert, Melinda (1997). Marching Together: Women of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252066368.

Honors and awards

- Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women, 1983.[4]

- Honored by the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights[1]

- Inducted into the D.C. Women's Hall of Fame, 1993[5]

- The A. Philip Randolph Institute's annual Rosina Tucker Award is named for her.

References

- Smith, Jessie Carney (2015). "Rosina Tucker". The Complete Encyclopedia of African-American History. Visible Ink Press. pp. 1470–1472. ISBN 9781578595839.

- "Civil rights activist Rosina Tucker honored at age 101". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. August 24, 1983.

- "Miles of Smiles, Years of Struggle". Paul Wagner Films.

- "The Evening Hours". The New York Times. October 14, 1983.

- "Commission Honors Five District Women". The Washington Post. 26 March 1993. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

External links

- "Rosina Tucker: A Century of Commitment". IIP Digital/U.S. Department of State.