Romance (meter)

The romance (the term is Spanish, and is pronounced accordingly: Spanish pronunciation: [roˈmanθe]) is a metrical form used in Spanish poetry.[1] It consists of an indefinite series (tirada) of verses, in which the even-numbered lines have a near-rhyme (assonance) and the odd lines are unrhymed.[1][2] The lines are octosyllabic (eight syllables to a line);[1][3] a similar but far less common form is hexasyllabic (six syllables to a line) and is known in Spanish as romancillo (a diminutive of romance);[1] that, or any other form of less than eight syllables may also be referred to as romance corto ("short romance").[3][4] A similar form in alexandrines (12 syllables) also exists, but was traditionally used in Spanish only for learned poetry (mester de clerecía).[1]

Poems in the romance form may be as few as ten verses long, and may extend to over 1,000 verses. They may constitute either epics or erudite romances juglarescos (from the Spanish word whose modern meaning is "juggler"; compare the French jongleur, which can also refer to a minstrel as well as a juggler). The epic forms trace back to the cantares de gesta (the Spanish equivalent of the French chansons de geste) and the lyric forms to the Provençal pastorela.

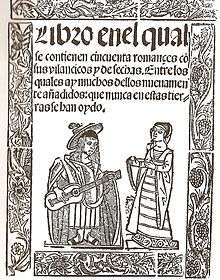

In the Spanish Golden Age, however, which is when the term came into wide use, romance was not understood to be a metrical form, but a type of narration, that could be written in various metrical forms. The first published collection of romances, Martín Nucio's Cancionero de romances (about 1547), was, according to Nucio's prologue, published not as poetry, but as a collection of historical source materials. Despite a considerable amount of poetic theory and history published during that period, there is no reference to romance as a term of meter prior to the nineteenth century. It did not mean an 8-syllable meter.[5]

Notes

- A. Robert Lauer, Spanish Metrification Archived 2010-06-20 at the Wayback Machine, University of Oklahoma. Accessed online 2010-02-10.

- Ana Rodríguez-Fischer, Prosa española de vanguardia, Volume 249 of Clásicos Castalia, Editorial Castalia, 1999. ISBN 84-7039-834-2. p. 92n. Available on Google Books.

- Romance, Diccionario de la Lengua Española, Vigésima segunda edición, Real Academia Española. Accessed online 2010-02-10.

- Rodríguez-Fischer p. 92n gives romance corto and romancillo as synonyms for one another.

- Daniel Eisenberg, “The Romance as Seen by Cervantes”, El Crotalón. Anuario de Filología Española, tomo 1 (1984), pp. 177-192, https://web.archive.org/web/20150702023853/http://users.ipfw.edu/jehle/deisenbe/cervantes/romance.pdf, retrieved August 4, 2015.