Common snook

The common snook (Centropomus undecimalis) is a species of marine fish in the family Centropomidae of the order Perciformes. The common snook is also known as the sergeant fish or robalo. It was originally assigned to the sciaenid genus Sciaena; Sciaena undecimradiatus and Centropomus undecimradiatus are obsolete synonyms for the species.

| Common snook | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Centropomidae |

| Genus: | Centropomus |

| Species: | C. undecimalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Centropomus undecimalis (Bloch, 1792) | |

| |

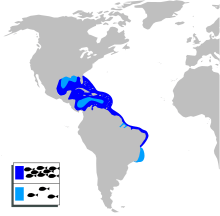

| Range map of the common snook | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Sciaena undecimalis Bloch, 1792 | |

One of the largest snooks, C. undecimalis grows to a maximum overall length of 140 cm (4.6 ft), but common length is 50 cm (1.6 ft). The IGFA world record is 24.32 kg (53 lb 10 oz) caught in Parismina Ranch, Costa Rica, by Rafael Montalvo.[3][2] Of typical centropomid form, it possesses drab coloration except for a distinctive black lateral line. It can also have bright yellow pelvic and caudal fins, especially during spawn.[4]

General ecology

Reproductive ecology

The common snook is a protandric hermaphrodite fish species.[5] The common snook's spawning season appears to span the months of April to October, with the peak spawning occurring during July and August.[6] Spawning typically occurs in near-shore waters with high salinities.[7] Following the spawning period, the juveniles then migrate to the brackish waters of the nearby estuarine environments.[7] When these juveniles mature, they return to the higher-salinity waters of the open ocean to join the breeding population.[7]

Habitat ecology

The common snook is an estuarine-dependent fish species.[8] Within estuaries, juvenile common snook are most often found inhabiting areas such as coastal wetland ponds, island networks, and creeks.[9] Despite being a euryhaline species of fish, the common snook does show a tendency to gravitate towards lower-salinity conditions in the early stages of its life.[10] By being able to adapt and thrive in both high- and low-salinity conditions through osmoregulation, common snook display a high level of habitat plasticity.[11] Common snook are opportunistic predators whose feeding habits indicate a positive relationship between their size and the size of their prey, meaning that as the snook grows, it feeds on larger and larger prey.[12] Common snook have been found to occasionally engage in cannibalism, though this behavior is rare.[13] This usually occurs during the winter when adult and juvenile common snook are in close proximity to one another within their estuarine habitats.[13] This form of cannibalism where the juveniles are fed on by the adults is referred to as intercohort cannibalism.[13] The adult common snook that do cannibalize juveniles most likely target them because the juveniles may be the largest of the available prey, so are nutritionally efficient to prey upon.[13]

Physiological ecology

Common snook, like many species of fish, are very in tune with their environments; even a slight change in their surroundings can have a significant impact on their behavior. For example, common snook are able to determine when to start and stop spawning based on the temperature and salinity of the water they inhabit, the amount of rainfall in the area, and whether or not the moon is full.[14][15] However, in some cases, disturbances in their environment can have very negative effects on the snook population. One example is the devastating results of a cold snap. Snook are very susceptible to cold temperatures, with the effects ranging from the complete halt of all feeding at a water temperature of 14.2 °C (57.6 °F), to the loss of equilibrium at 12.7 °C (54.9 °F), to death at a temperature of 12.5 °C (54.5 °F).[16] Recently, a cold snap in January 2010 resulted in a 41.88% decline in nominal abundance of the common snook population in southwest Florida from the previous year and a 96-97% decrease in apparent survival estimates.[17]

Distribution and habitat

C. undecimalis is widespread throughout the tropical waters of the western Atlantic Ocean from the coast of the North Carolina to Brazil including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.[18] Snook likely originated in Central America, and changes in the earth's climate brought the snook to Florida. During a great warming trend after the Ice Age, snook moved northward along the Mexico shoreline. They followed the perimeter of the Gulf of Mexico, along the west and east coasts of Florida. Massive snook are found in Central America, although they seem to look a little different because of the weather and water quality, but they are the same. No restrictions exist in most of Central America on the size or quantity of snook one can keep, consequently many locals have been keeping and killing these large snook for quite a while.[19] Occurring in shallow coastal waters (up to 20 m (66 ft) in depth), estuaries and lagoons, the fish often enter fresh water. They are carnivorous, with a diet dominated by smaller fishes, and crustaceans such as shrimp, and occasionally crabs.[20]

Human interest

Three United States Navy submarines have been named for this species, USS Robalo (SS-273) and USS Snook (SS-279) in the Second World War and USS Snook (SSN-592) in the 1950s.

Considered an excellent food fish, the common snook is fished commercially and foreign-caught fish are sold in the US. When cooking snook, the skin must be removed, because it imparts an unpleasant taste, described as soapy, to the fish.[21]

Snook are also prized as game fish, being known for their great fighting capabilities.[22] The IGFA All Tackle World Record for Common snook stands at 53 lb 10oz (24.32 kg) caught by Gilbert Ponzi near Parismina Ranch, Costa Rica. Previous world records were caught in Fort Myers, Florida and Gatun Spillway Canal Zone, Panama.[23]

Protection in Florida Gulf Coast

"At the June 2012 Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) meeting, Commissioners voted to keep the recreational harvest of snook in Gulf of Mexico waters closed through Aug. 31, 2013. This closure will offer the species additional protection after a 2010 cold kill detrimentally affected the population. Snook closed to harvest in Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic waters in January 2010 after a severe cold kill affected snook population number."[24]

All snook are "catch-and-release only" in the Gulf of Mexico until August 31, 2013. At that time, the FWC can choose to open or close snook harvest for another season. The commercial harvest or sale of snook is prohibited by the same regulations.

At the June 2013 FWC meeting, commissioners voted to let the recreational harvest of snook reopen in Gulf of Mexico waters from September 1 that year. The next stock assessment for snook was scheduled for 2015, but has not yet occurred as of June 2016, effectively leaving the fish under a protected status.[25]

References

- Mendonça, J.T.; Chao, L.; Albieri, R.J.; et al. (2019). "Centropomus undecimalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T191835A82665184. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T191835A82665184.en. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2019). "Centropomus unidecimalis" in FishBase. December 2019 version.

- "IGFA World Record - All Tackle Records - Snook, common". igfa.org. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- "Common Snook - Centropomus undecimalis - Details - Encyclopedia of Life". eol.org. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Perera-García, M.A.; Mendoza-Carranza, M.; Contreras-Sánchez, W.M.; Huerta-Ortíz, M.; Pérez-Sánchez, E. (2011). "Reproductive biology of common snook Centropomus undecimalis (Perciformes: Centropomidae) in two tropical habitats". Revista de Biología Tropical. 59 (2): 669–681.

- Tucker, J.W.; Campbell, S.W. (1988). "Spawning season of common snook along the east central Florida coast" (PDF). Florida Scientist. 51 (1): 1–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-28. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- Gracia-Lopez, V.; Rosas-Vazquez, C.; Brito-Perez, R. (2006). "Effects of salinity on physiological conditions in juvenile common snook Centropomus undecimalis". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 145 (3): 340–345. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.07.008.

- Taylor, R.G.; Grier, H.J.; Whittington, J.A. (1998). "Spawning rhythms of common snook in Florida". Journal of Fish Biology. 53 (3): 502–520. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1998.tb00998.x.

- Stevens, P.W.; Blewett, D.A.; Poulakis, G.R. (2007). "Variable habitat use by juvenile common snook, Centropomus undecimalis (Pisces: Centropomidae): applying a life-history model in a southwest Florida estuary" (PDF). Bulletin of Marine Science. 80 (1): 93–108.

- Peterson, M.S.; Gilmore, G.R. (1991). "Eco-Physiology of Juvenile Snook Centropomus Undecimalis (Bloch): Life-History Implications" (PDF). Bulletin of Marine Science. 48 (1): 46–57.

- Rhody, N.R.; Nassif, N.A.; Main, K.L. (2010). "Sarasota, FL, US, p. 30. Rhody, N. R., Nassif, N. A., and Main, K. L. 2010. Effects of salinity on growth and survival of common snook Centropomus undecimalis (Bloch, 1792) larvae". Aquaculture Research. 41 (9): 357–360. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2109.2010.02511.x.

- Blewett, N.R.; Hensley, R.A.; Stevens, P.W. (2006). "Feeding habits of common snook, Centropomus undecimalis, in Charlotte Harbor, Florida" (PDF). Gulf and Caribbean Research. 18: 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-28. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- Adams, A.J.; Wolfe, R.K. (2006). "Cannibalism of juveniles by adult common snook (Centropomus undecimalis)" (PDF). Gulf of Mexico Science. 24 (1/2): 11.

- Peters, K.M.; Matheson Jr., R.E.; Taylor, R.G. (1998). "Reproduction and early life history of common snook, Centropomus undecimalis (Bloch), in Florida" (PDF). Bulletin of Marine Science. 62 (2): 509–529.

- Aliaume, C.; Zerbi, A.; Miller, J.M. (2005). "Juvenile snook species in Puerto Rico estuaries: Distribution, abundance and habitat description". Proc. Gulf Carib. Fish. Institute. 47: 499–519.

- Shafland, P.L.; Foote, K.J. (1983). "A lower lethal temperature for fingerling snook (Centropomus undecimalis)" (PDF). Northeast Gulf Science. 6: 175–177.

- Adams, A.J.; Hill, J.E.; Barbour, A.B. (2012). "Effects of a severe cold event on the subtropical, estuarine-dependent common snook, Centropomus undecimalis" (PDF). Gulf and Caribbean Research. 24: 13–21.

- "Common Snook - Centropomus undecimalis - Details - Encyclopedia of Life". eol.org. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- "Costa Rica Snook - Fish For Snook". Fish For Snook. Archived from the original on 2016-01-24. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- "Common Snook - Centropomus undecimalis - Details - Encyclopedia of Life". eol.org. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- "Snook: A rare seasonal treat that's worth the effort". naplesnews.com. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- "Common Snook - Centropomus undecimalis - Details - Encyclopedia of Life". eol.org. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- "Snook, Common". igfa.com. International Game Fish Association. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- "Snook". Myfwc.com. Retrieved 2016-06-24.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 28, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2004). "Centropomus undecimalis" in FishBase. October 2004 version.

- "Centropomus undecimalis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2004-12-20.

- Snook or Robalo types as game fish

- Zeigler, Norm (2007). Snook on a Fly: Tackle, Tactics, and Tips for Catching the Great Saltwater Gamefish. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0201-4.

- FWC Regulations on snook 2017

External links

- Photos of Common snook on Sealife Collection