Ripley Ville

Ripley Ville or Ripleyville was an estate of model houses for the working classes in Broomfields in the East Bowling ward of the City of Bradford in West Yorkshire, England.

Started in 1866 the development was built for the industrialist, politician and philanthropist Henry William Ripley. It was intended as a commercial development of model houses but when completed in 1881 had many aspects of an industrial model village – although residency was not limited to Ripley's employees. It was the only model village in the Borough of Bradford[1] and can be compared with Akroydon in Halifax, built by Ripley's friend and schoolmate Edward Akroyd, Saltaire and model housing schemes in other West Riding textile towns.[2] Ripley Ville contained 196 workmen's cottages, a school and teacher's house, a church, allotment gardens and, on a separate site about a half-mile distant, a vicarage and ten almshouses which are still standing although all the other buildings had been demolished by 1970.

Background

By the 1860s Ripley was managing partner of the Bowling Dye works, founded by his grandfather in 1808. In 1822 the dye works had relocated from West Bowling to a site in Spring Wood next to the Spring Wood Colliery pumping shaft – which supplied the works with steam and water. The works employed 18 men and boys. From 1835 as the junior partner Henry was "regarded as the boss of the dyehouse".[3] He built up the business to be the biggest dye works in Yorkshire. From the Bowling Iron Works he purchased the freehold of the dye works and about 100 acres of land surrounding it and subsequently built up the landholding to about 130 acres.[4] The landholding added to the available water supply – "The whole of the water required for the supply of the works is an available source of 1,250,000 gallons per day". To the dye works income he had added income from several mills[5] rented out on a "room and power" basis, from a water works (supplying 600,000 gallons per day) and a gas works. He was recognised as one of Bradford's "big four" industrialists alongside Titus Salt, Samuel Lister and Isaac Holden. As a councillor, JP and public figure Ripley was deeply involved in the debates which engaged the recently (1847) incorporated borough council and its citizens.

After four decades of rapid economic and population growth Bradford had some of the worst housing and sanitary conditions in the UK and about the lowest life expectancy. A sanitary commissioner reported – "Taking the general condition of Bradford, I am obliged to pronounce it to be the most filthy town I visited."[6] In 1850 Titus Salt relocated his mills outside of the town and embarked on developing his model community at Saltaire. Bradford's Building and Improvement Committee reported in 1855 to the council "Your committee again beg to draw the attention of the Council and the public to the continued practice of building houses back-to-back. Out of 1401 sanctioned, 1070 or 76.9 per cent are laid out upon that objectionable principle.".[7] Bradford council passed a series of building bylaws (1854, 1860, 1866 and 1870[8] ) intended to ensure that new houses were of a decent standard. The bylaw of 1860 effectively banned construction of back to back houses which had been the predominant form of working class housing for 30 years.[9] The building interests mounted a campaign to have the bylaw rescinded, maintaining it was impossible to build "through" houses at a price that working-class people could afford and as evidence pointed to the precipitate fall in new building starts. In the elections of 1865 the chairman of the Building and Improvement Committee lost his seat and was replaced by a councillor more sympathetic to the building interests. In 1866 Bradford council issued a revised by-law which allowed construction of "back to backs" provided they met stringent requirements for space, ventilation, water supply and sanitary provision. These "tunnel backs" became Bradford's predominant form of working-class houses during the next 20 years. The council approved no further plans for back to back houses after the 1870 bylaw but the builders had a sufficient stock of approvals to continue building them well into the 1890s.[10]

Ripley was not convinced by the arguments of the speculative builders. In November 1865 he issued a prospectus for the construction of 300 "Working-men's dwellings" on his own land.[11] They were four-bedroom through houses with rear yards and front gardens and equipped with an internal WC. The houses were intended for sale to small landlords and owner occupiers with a provision for rental purchase and some renting. The Bradford firm Andrews and Pepper were appointed architects. The specification for the Ripley Ville houses was influenced by the proponents of model housing, such as J.Hole[12] and Godwin, editor of "The Builder" and the practices of contemporary model builders in the West Riding. By the mid 1860s the views of the improvers had moved on from the provision of basic accommodation to considerations of lighting, ventilation, heating, storage, privacy and open space.[13] The design of the Ripley Ville houses incorporated these enhanced standards, and in several respects exceeded them.

Construction

Planning permission to build 254 houses was granted on 24 January 1866. Four invitations to tender appeared in the Bradford Observer – the first on 23 March 1866 and the fourth and final on 21 March 1867.[14] amounting in total to 200 houses. The reduction in the number of houses to be built in part reflected the decision to include a school. Planning approval for the school was given 8 June 1867.

All the houses were completed by early 1868 and the school was in use by autumn that year. Houses built under tenders 1 and 2 were completed with internal WCs in the cellar. A change of plan in spring 1867 led houses built under tenders 3 and 4 having external ash closets. Tenders 1 and 2 houses were retrofitted with external ash closets and the WCs removed. Reasons for the change remain obscure.[15]

On 11 December 1868 the Bradford Ten Churches Building Committee announced its intention to build its tenth church in Ripley Ville on land donated by Ripley.[16] T.H and F Healey who designed Our Lady and St James Church in Worsbrough were appointed architects. St Bartholomew's Church was consecrated in December 1872. The architecture and townscape of Ripley Ville was complete and remained substantially unchanged until demolition a century afterwards. In 1875 a vicarage for the incumbent of St Bartholomew's was completed on land given by Ripley at the extreme southern boundary of his landholding. At that time it was a semi rural environment. In 1881 ten almshouses were built at the cost of Ripley on a plot close to the vicarage. Six of the almshouses replaced almshouses built in 1857 on a site which had been partly taken over by the Thornton Railway.[17]

Site and architectural scheme

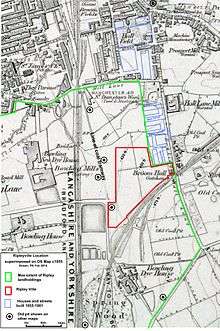

In 1865 more than 80 acres of Ripley's land holding were still undeveloped. The area was dotted with the Bowling Iron Company's former mine workings. Several old mine shafts had been converted to wells to provide the dye works with its soft water supply. Ripley Ville occupied most of the Broom Hall Estate: Broom Hall was a working farmhouse into the 1860s. The northern part of the estate had been acquired by the Great Northern Railway Company (GNR) to build the Bowling Curves that opened in 1867. The site chosen for Ripley Ville had the disadvantage being irregularly shaped with steep gradients. Its central street fell 40 feet over a distance of 300 feet but it was relatively free of old mine workings and contiguous to the urban development along Hall Lane which gave access to the town centre.

The site's gradients and the irregular shape determined the architectural scheme. Thirteen terraces of houses along four residential streets were laid out on a north–south axis. The outer streets, Vere Street and Ripley Terrace had houses on one side and full width carriageways. The internal Sloane and Saville Streets had 6 ft pedestrian walkways separating the front gardens. The cobbled back streets provided access for wheeled traffic and contained the mains services (water, gas, sewerage). Three streets on an east-west alignment (Ellen Street, Linton Street and Merton Street) provided access to the residential streets and locations for retail premises and public buildings.

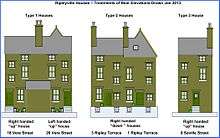

The development had 196 houses with three sizes of house, 25 of the largest Type 1 houses in two terraces, 140 of the intermediate Type 2 houses in nine terraces and 31 of the smallest Type 3 houses in two terraces. The front elevations, apart from a small difference in width, were identical for each type, and permitted a unified architectural scheme.

The church was completed four years after the houses and school by other architects and it seems that Andrews and Pepper's scheme anticipated a major building at this point. The impact of the completed scheme was dramatic, especially when viewed from the east. Ripley terrace was virtually level along its 750 ft length. The slight fall of about 4 ft was compensated for by building up gardens walls in the lower section so that doors and windows remained in alignment. Behind the south section of the terrace the school buildings rose above the house roofs with the pinnacle of the clock tower about 50 feet above the roof ridge of the houses. Behind the central and north sections of Ripley Terrace the roof lines of the successive terraces rose in echelon with the gable of St Bartholomew's rising 40 feet above the highest roofs. The pyramidical theme was repeated in the front elevations of the terraces.

Architectural punctuation of the terraces' front elevations was provided by tall gables to the terminal and central houses. In the north section the outer terraces had gables intermediate between the central and terminal houses. Different designs of gable window were used in different terraces. Left and right handed houses were used to provide symmetry. In a left-handed house the front door was to the left of the ground floor window. In a-right handed house it was to the right. The handedness changed in the centre of the terrace and was marked by a gable house. Between the gable house and its partner was a double chimney stack. Thus there were no chimney stacks on the terminal walls of the terrace and each terminal wall had a front door adjacent to it.

Externally the houses were of hammer-dressed Bradford stone set in black ash mortar with sills and lintels of sawn stone. Brick was used for internal walls and liners to external walls but was nowhere externally visible. House roofs were Welsh slate. Privies were of hammer dressed stone with Elland Flag roofs. Back yard walls were of hammer dressed stone, about 4 ft 6 in high and with triangular capstones. Ripley Terrace and Vere Street front garden walls were about 3 ft high with broad rounded capstones surmounted by wrought iron railings. Gardens of the internal "front" streets had wrought iron railings of about 3 ft 6 in height set on stone plinths and with wrought iron gates.

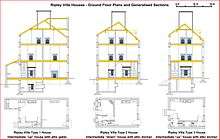

All three types of house had two attic bedrooms, two first floor bedrooms and a cellar. Ground floor designs varied between the types.

Type 1 houses had a frontage of 16 ft 7 inches and a depth of 28 feet. They had two large ground floor rooms and a scullery in a back extension. The cellar was fitted out as a "cellar kitchen" with a sink and range. The cellar also contained a WC and a coal store.

Type 2 houses had a frontage of 15 ft 9" and a depth of 24 feet. They had a large front ground floor room and a smaller back room. The basement contained a storage cellar, WC in houses built under tenders 1 and 2 and coal store.

Type 3 houses had a frontage of 16 ft 7" and a depth of 20 feet. They had a single "through room" and small scullery on the ground floor. The basement contained a storage cellar, a coal store and a second enclosure. No WCs were fitted to type 3 houses, all of which were built under tenders 3 and 4.

All habitable rooms in the houses had gas lighting. The streets were gas lit supplied from Ripley's gas works in Mill Lane. All habitable rooms had a fireplace or range. In the bedrooms fireplaces were decorative cast iron. Type 1 houses had ranges in the back room and cellar kitchen and a polished slate fireplace in the ground floor front room. Type 2 houses had ranges in both ground floor rooms. Type 3 houses had a range in the single ground floor room.

Internal staircases from the ground floor were constructed of stone. Attic staircases were timber. The staircases were well lit by windows in the rear elevation. Cellars and back rooms had stone flagged floors, other floors were suspended timber

Front attic bedrooms were lit by casement windows in the dormer or on the case of gable houses a variety of decorative window designs. All other windows above ground apart from the back attic bedrooms of end of terrace gable houses, which had sky lights were double opening sashes of large size. Provision was made for built in storage. Cellars were fitted with stone shelves and three storage alcoves set into the wall. Living rooms had a cupboard mounted on a set of drawers. Walk in clothes closets were provided on the attic landings. In keeping with other Andrews and Pepper buildings all materials were of excellent quality and standards of workmanship and finish very high.

Context

Discussion about the superiority of the Ripley Ville houses compared to the average working-class houses of the time focused on the provision of WCs. In November 1866 Mr Gott, the corporation's chief engineer gave evidence to the Pollution of Rivers Commission.[18] He said there were 26,000 houses in the town and 19,500 privies – of which 1,500 were WCs, 6,000 ash pits and 12,000 pail closets. Half of all houses, 13,000 in total, did not have sole use of a privy and WCs were installed in 5.7% of the total housing stock. WC's were a middle class preserve and virtually unknown in working class dwellings[19] – other than the houses being constructed in Ripley Ville.

A more useful comparator is habitable rooms per house and usable space in sq ft. The typical working class cottage built in the 1850s was a "one up and one down". The houses in Fig.4 in Hird Street (built c.1858, under the 1854 bylaw) are typical of this type- one is included in the table as a comparison with the Ripley Ville houses.

| Measure | Type 1 house | Type 2 house | Type 3 house | c1858 back to back | c1875 tunnel back |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usable space sq ft | 1135 | 853 | 703 | 401 | 510–620 |

| Habitable rooms | 7 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3–4 |

Also included is an example of tunnel back to backs which were built in large numbers in Bowling after the 1866 bylaw change. The tunnel gave access to the rear two houses and a group of four privies. Most such houses exceeded the bylaw minimum (the 1870 bylaw still permitted construction of the one up and one down) by including a side scullery and often a small front garden. In the example in the table the ground floor had a good size living room and a side scullery with access to the tunnel. Such houses had either two or three bedrooms, the third being in a flying free hold over the tunnel. Even the three-bedroom type was considerably smaller than the type 3 Ripley Ville house.

The type 1 and 2 Ripley Ville houses were comparable in size to the houses built at Saltaire for supervisors and managers and to contemporary lower-middle-class houses elsewhere.

It is difficult to judge how the example set by developers such as Ripley affected the standards of speculative builders. Writing in 1891 William Cudworth had no doubt about the beneficial impact of the improved dwellings movement over the longer term. "There can be no question that the housing of the operative classes is comparably better than it was fifty years ago. There is more provision for separate bedrooms.... The cottage of today with its wide streets and separate closets is a fair approach to sanitary perfection".[20] Working-class houses comparable in space and number of rooms to the Ripley Ville houses started to be built in Bowling from about 1895 and were built in large numbers between 1900 and 1914. From about 1906 they usually had a bathroom with a WC on the first floor.[21] Use of a transverse staircase as opposed to the longitudinal staircase in the Ripley Ville houses allowed access to a bathroom in addition to the rear bedroom. Retro fitting of bathrooms to the earlier houses of this type was accomplished by partitioning the rear bedroom. The transverse staircases were very steep compared to the Ripley Ville staircases and had no direct lighting. In most houses of this period attic bedrooms were lit only by skylights and did not have fireplaces. Although this type of house was comparable to the Ripley Ville houses of a half century earlier some aspects of the design were less satisfactory.

The 1911 census shows that the recently built houses were occupied by the upper stratum of the working classes with a high proportion of white collar workers and school teachers. The lower strata of the working classes had to await the building of council estates in the 1920s and 1930s to obtain three and four-bedroom houses with a bathroom and garden.[22]

School

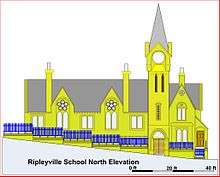

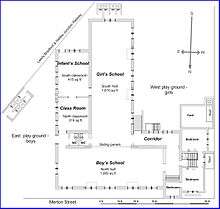

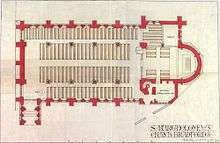

The school building was financed by Ripley and run by the non-denominational British and Foreign School Society It was designed by Andrews Son and Pepper in a gothic revivalist style. The halls and classrooms were on a single level with service rooms in a basement. Internally the ground floor (total area 4,192 sq. ft.) was mainly taken up by two large halls of double height. The south hall of 1600 sq. ft. accommodated the girls primary school and the northern hall of 1300 sq. ft. accommodated the boys. Two smaller classrooms accommodated the infants.[23] Later photographic evidence suggests that the class room block as built varied from the plan. Instead of two unequally sized classrooms with an entrance lobby to the north there were two equally sized rooms separated by a centrally placed entrance lobby. The entrance door was beneath a gabled semi-dormer with a round window in the gable – very similar to the gables of the north façade.

The formal entrance to the school was through a carved and columned arched doorway on the ground floor of a very decorative clock tower. The tower was about 75 ft in height and had four clock faces – illuminated at night.

Each of the two play grounds had a pupils' entrance: junior girls and infants in the west and junior boys in the east. Boundary walls, gates and railings to the street frontages were similar to those of the workmen's cottages.

The large halls were separated by sliding panels which could be drawn back to create a single space of about 2,900 sq ft. which was used for social events and public meetings. Contemporary press reports refer to the "fine and spacious hall" where "between four and five hundred people sat down to tea."

The teacher's house had three levels and apart from ornate external stone carving was similar in size and features to the workmen's cottages. The basement contained a storage cellar, pantry and space for a WC. As with the houses and school building it is not certain that any WC's were actually installed. The ground floor contained two living rooms, one with a sink, range and access to a private yard. An entrance hall opened to the stair hall. At the mezzanine landing of the stair was a door into the school corridor. On the first floor there were two bedrooms, each with a fireplace, and a smaller bedroom in the clock tower. Flues from the four fireplaces were carried to a single central chimney stack supported by an arch (hidden in the roof space) across the stair hall. This was unusual and expensive form of construction, but visually impressive.

Heating of the halls and classrooms was by coke stoves. In the 1880s Ripley's estates department converted the north hall for use as offices. A central heating boiler was installed in the basement and the coke stoves were replaced by radiators. Some features of the building prefigured, on a smaller scale, Andrews and Pepper's design for the grammar school in Manor Row (1872).

St Bartholomew's Church

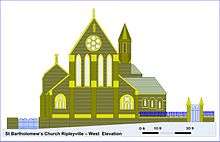

St Bartholomew's was the last church constructed under the Bradford Ten Churches building Campaign inspired by Charles Hardy, managing partner of the Low Moor Iron works and a leading Anglican layman. Ripley agreed to provide a site at no cost after he and Hardy had inspected it in 1868.[24] The building cost in excess of £7,000, was largely met by donations from the Hardy family. The church contained a chapel with a window dedicated to the memory of Charles Hardy

In 1870 T. H and F. Healey were appointed architects. Planning permission was given in January 1871[25] and the Incorporated Church Building Society (ICBS) approved the design and a grant towards the cost. Site preparation works involving large-scale engineering started immediately. The foundation stone was laid at a service of dedication in April 1871 and the church was consecrated in December 1872. The bell turret was finished in 1874 when ICBS paid its grant towards the costs

Press articles covering the dedication[26] and consecration[27] ceremonies provide a detailed account of the architecture. The style was a simplified Early English. External masonry was Bradford stone and its roof was made of green Westmoreland slate. The churchyard had low stone walls with decorative wrought iron railings and gates. Internally the church walls were of pressed brick with moulded capitals to the columns and arches of polychrome brick – reportedly, "a very cheerful effect". Its 740 sittings were provided free. The church occupied the dominant site in Ripley Ville and with the west gable apex 70 ft above street level the external appearance was very impressive. The architectural carving was executed by Charles Mawer.[28]

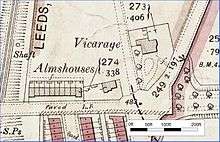

Vicarage and almshouses

The first vicar, Mr Rice, lived in a rented house at 22 Edmund Street which still exists. The parish, under the leadership of Ripley, decided a more permanent arrangement was needed. Ripley donated the site (0.406 acres) on New Cross Street about half a mile south of the church. The architects were T.H and F Healy who placed an invitation to tender in the Bradford Observer on 26 February 1874. The vicarage was completed in 1875, costing £2,050. The Ecclesiastical Commissioners provided £1,300 and the parish raised £750 from benefactions.[29] Contemporary press articles describe it as "on the scale of a "gentleman's residence" and as having "both day and night nurseries".[30] No plans survive but from the large scale Ordnance Survey map its ground area can be measured as 2036 sq.ft compared with the 505 sq.ft. ground area of a type 1 Ripley Ville house.

By the late 1920s the vicarage was uneconomic. Vicars' salaries were insufficient for domestic servants and it may have been affected by mining subsidence.(The adjacent Durston's House was demolished about that time.) It was sold to a property developer who demolished and replaced it with a row of houses by 1931. The parish took the lease of a detached house at 205 Hall Lane until 1942 when on amalgamation of the St Luke's parish with St Bartholomew's the former St Luke's vicarage in Caledonia Street became available. Both the vicarages were early-19th century houses of elegant classical design. The Caledonia Street house had been built for a local mill owner in 1834

In 1881 Ripley paid for ten almshouses in New Cross Street a short distance from the vicarage. Six replaced alms houses built in 1857[31] by his parents near their house, Bowling Lodge. The old almshouses site had been partly taken over by the GNR line from Ripleyville to Thornton. The commemorative plaque of 1857 was re-affixed to the new almshouses which are grade II listed.[32] The architect was James Ledingham[33] who had worked as an assistant to Andrews and Pepper.

Plans deposited by Ledingham[34] show that each house had a ground area of about 350 sq. ft.(the projecting end of terrace houses were slightly larger) with a frontage of about 18 ft. On the ground floor front was a living room containing a range. To the rear was a scullery with a sink and access to a back yard containing an ash house, coal store and a gate to a service road. On the first floor front was a bedroom with a fireplace and walk in wardrobe. On the mezzanine level was a WC.

The relative isolation of the area where the vicarage and almshouses were built was greatly reduced in 1881 when the GNR opened Bowling Junction station, about 50 yards distant from the almshouses. It had services to Bradford (about 5 minutes journey time), Leeds, Halifax and Wakefield.

Occupancy of the almshouses was not limited to former Ripley employees but was open to all old residents of Bowling. Occupants received an allowance of 3/- per week.

Retail premises

Six end terrace houses adjoining Linton Street and two adjoining Ellen street were retail premises at the time of the 1871 census. All except No 2 Vere Street continued in commercial use until demolition. Architectural and structural changes were in most cases carried out at the time of construction.

Ripley would not allow the sale of beer in Ripley Ville – although the 1872 Smith's Directory records Stephen Gibson of No 2 Linton Street as a grocer, tea dealer and beer retailer.[35] Initially there was no public house but residents could drink at the Locomotive Inn (which predated Ripley Ville) at No 7 Ellen Street or in Hall Lane at the Bowling Hotel or any of the four beer retailers recorded there in Smiths Directory.

During the 1870s the shop at No 2 Linton Street was joined to the adjacent house (40 Saville Street) and modifications undertaken. The 8-bedroom building was run by Mrs Gibson as a shop and coffee tavern and probably a temperance hotel. In the 1890s (after Ripley's death) Benjamin Spenser[36] obtained a beer license. Under the name Gibson Hotel it continued as the village pub until demolition.

In 1874 the Co-op opened a store at No 10 Ellen Street replacing temporary store at No 5 Ellen Street. Branch 11 was an imposing building and continued trading until demolition in 1960.

Early history

Ripley's expectations for the model development were not fully met. He had intended the houses should be for outright purchase – but very few, mainly the end terrace houses adapted for retail use, were purchased outright. A scheme for rental purchase was abandoned because of low take up. Most of the houses were offered for rent but the take up was slow. Ripley's political opponents accused him of charging exorbitant rents.[37] The 1871 census returns bears out the slow take up and high rent levels. In one terrace of 13 houses 7 were unoccupied. Overall 17 of the 196 properties were unoccupied and 24 were in multiple accommodation.

In 1868 the building society movement was still in its infancy. Caffyn[38] notes – "By the late 19th century many building societies' requirements excluded less affluent workers from membership. Borrowers from the Bradford Equitable Building society and the Freehold Land Society for example, were largely foremen, clerks, school-masters, shopkeepers and the like.." Only in the first decade of the 20th century were significant numbers of working-class people in south Bradford able obtain a mortgage for house purchase

The Bradford Observer gave an impression of an active community life in Ripley Ville. Cricket and football teams were successful in local leagues. Meetings and other events took place in the school hall on a regular basis. There are reports of teas and tea evenings, usually with Ripley hosting the event and making a speech. The opening of the Co-op store was marked by an event at Ripley Ville school.[39] Speeches were made by officers of the Bradford Industrial Society and by the Rev A.B Cunningham, a travelling lecturer of the University Extension Movement.[40] Other meetings were held to raise money for the vicarage and church organ, and to celebrate its installation in 1878. In 1881 when it was announced that the parish of St Bartholomew's had a debt of £800, Ripley led the fund raising campaign and it was paid off in months. The tone of press reports show Ripley greatly enjoying himself as leader of his new community

The Thornton Railway, of which Ripley was an enthusiastic proponent, opened in 1878 with a station, St Dunstan's, in Ripley Ville. The following year the line was extended to Halifax and in 1883 to Keighley. Ripley Ville was a node on the expanding rail network.[41] With services to Bradford, Leeds, Halifax, Wakefield and intermediate villages and suburbs the station expanded commercial and job opportunities for the residents.

A main sewer from The Roughs to central Bradford was completed by Bradford Corporation. The Ripley Ville sewer system, installed 1866-8 but out of use following the change of plan over WCs, was connected to it. Subsequently, the external ash closets of the Ripley Ville houses were converted to WCs.

Sir Henry Ripley (knighted in 1881) died in early 1882. His younger son, also Henry, succeeded him as manager of the dye works. After his death most of Sir Henry's property, including the Ripley Ville estate, was administered by a body of trustees. The junior school ceased to operate in the early 1880s when the Board School took its pupils. Ripley's trustees and their estates office moved into the junior school accommodation. The infants school continued until just before the First World War. Its premises continued in use as a parish hall and village social centre until after the Second World War.

Successive census results give a picture of a prosperous and stable community. Ripley had achieved his aim of providing houses for the working classes but the census returns of 1881 and 91 show that the residents represented the upper stratum of working class occupations. White collar occupations were well represented, especially in the type 1 houses of Vere Street. Skilled craftsmen and self-employed tradesmen were numerous, with the construction and engineering trades well represented. Some residents had become members of the middle classes. Edward Wright of no. 83 Ripley Terrace, described in earlier censuses as a master mill-right, engineer and employer of labour, is described in later censuses as the owner of an engineers' tool supply company.

Subsequent history

In 1899 ownership and control of the dye works passed to the newly created Bradford Dyers Association. Members of the Ripley family ceased to have any personal relationship with Ripley Ville.

In 1896 the Midland Railway obtained an act of Parliament authorising it to build a through railway from its main line at Royston to connect with its existing tracks at Bradford Foster Square.[42] The proposed line of railway passed under Ripley Ville. The Midland's cash offer of £6,000 for the purchase of Ripley property was unacceptable to the Ripley Trust who also felt that there was a direct threat to the soft water supply to the dye works. An Arbitration hearing in 1900[43] awarded the Ripley Trust £14,000 for 3 acres of land in Ripley Ville. This included 4 terraces of houses and a strip of land across Ladywell Fields. After another Act of Parliament in 1912 and several changes of plan the Midland Railway decided, in the changed economic circumstances after the Great War, to abandon the scheme. Bradford Corporation (who were wholly in favour of the scheme and deeply regretted its abandonment) agreed to buy all the land acquired by the Midland. This included, in addition to much land in the centre of the city, the four terraces of houses in Ripley Ville and Ladywell fields. Ladywell Fields were designated as a public park. Management of the four terraces of houses passed to the Borough's housing department.

With control of Ripley Ville rented houses divided between Ripley's Trustees and the Corporation there were no co-ordinated attempts to upgrade and modernise the estate. Both landlords followed a policy of minimum maintenance. Ripley's Trustees undertook no external painting after about 1920. Linton Street and Merton Street remained un-adopted. They had never been paved other than with a scattering of blast furnace slag. Vere Street, Ellen Street and the back streets had cobbled carriageways and flagged pavements and remained in a fairly decent state. The council "tarmaced" Ripley Terrace when it became a bus route.

There was no electricity supply to the houses until 1938 when supply cables were laid by the municipal power authority. Ripley's Trustees required tenants to contribute to the cost of connection (£60 in 1958) so take up was slow. Some houses still used gas lighting in the 1960s. By that time the estate had a very neglected appearance. Removal of the iron gates and railings "for the war effort" in 1941 had made maintenance of front gardens very difficult – especially in the internal rows where there were no garden walls.

Under the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, Bradford Corporation adopted "The Bradford Development Plan" in 1951. (Mainly authored by Stanley Wardley, the city's Chief Engineer) The plan envisaged large scale demolition of 19th-century houses in Bowling and redevelopment for "light industrial" use. In the late 1950s the Corporation's demolition program approached Ripley Ville. By 1958 the houses in Hird Street and most of those in Hall Lane had been demolished. The Ellen Street co-op and St Bartholomew's church had been demolished by 1962. In 1970 the Ripley Ville houses and School were demolished and the site levelled for redevelopment. There were few protests and no mention of the desirability of preserving an historical and architectural heritage.

21st century

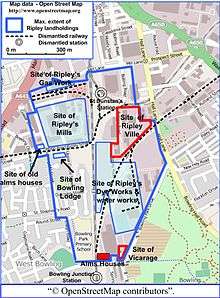

Apart from minor changes the pattern of land use on Ripley's land holdings and the built environment established at the time of Henry Ripley's death continued into the 1960s and until the demolition of Ripley Ville in 1970. Subsequently, Ripley's dye works and mills have also been demolished and redeveloped and previously undeveloped land has been built on. In recent years (2014) even some major railway engineering features have been obliterated and it is now difficult to see how former land use relates to the modern landscape. Fig.16 shows some of the earlier features superimposed on a recent (2014) street map.

Sources of information

Unlike his contemporaries Titus Salt and Samuel Cunliffe Lister, Henry William Ripley had no biographer. Information about Ripley and Ripley Ville must be drawn from a wide range of sources. Principal sources are listed in the bibliography. Some must be treated with caution.

Henry William Ripley and his model village of Ripley Ville were well covered by contemporary press articles. Bradford had a very active local press at that time. Rhodes "Bradford Past and Present" provides a history and list of publications to 1890.[44] The article is anonymous but the author was probably William Cudworth. The Bradford Observer in particular is a very rich source of comments and reports.[45] Digitised copies are available on the British Newspaper Archive website. Copies of other local publications are held at Bradford Library.

The various works of the local historian and reporter William Cudworth, a younger contemporary of Ripley, are also a valuable source of information. In the "History of Bowling" he provides an account of the geology and mining history of the area and describes the deepening of former pumping shafts to the Rough Rock level to tap the soft water aquifer. He provides a history of the dye works and in his references to Ripley Ville gives details of the rental purchase scheme and its abandonment. However, the usually reliable Cudworth misdates".[46] the building of Ripley Ville to 1863–4 – an error perpetuated by some later authors.

Cudworth's "Historical Notes on the Bradford Corporation " provides an account of the development of water and sewage works and the building by-laws.

Few publications between Cudworth's death and the 1970s dealt directly with Ripley, Ripley Ville or the history of Bowling and for this period newspaper reports are the principal source of information. The "Centenary Yearbook" (1947) records that Bradford's sewage treatment problems were not properly solved until completion of the Esholt scheme in the early years of the 20th century and that the water supply problems continued until completion of the Nidderdale scheme in the inter war years.[47] Writing in 1982 David Wright noted[48] in the Introduction to "Victorian Bradford" that "Although Bradford produced some eminent historians of the city in the Victorian age, its history during the first half of the twentieth century remained sunk in a mass of antiquarianism and neglect. Only on the last fifteen years or so has there appeared a significant and fruitful crop of academic historical studies". These studies from about 1970 were often inspired by Jack Reynolds of the University of Leeds or sponsored by Bradford Library and the recently (1966) chartered Bradford University.

The unpublished dissertation by Derek Pickles shows that the eastern and southern boundaries of Ripley's landholding followed the lines of former coal tramways, and that Ripley Road which bisected the dye works was also a tramway route. Richardson's "Geography of Bradford" (1976) provides a modern spatial analysis and shows the impact of earlier transport and mining features on the location of subsequent industrial and residential developments. A paper "All Change" (1986) presented to the Bradford Society of Antiquaries describes how the Midland Railway Company's scheme for a through line led to divided ownership of the Ripley Ville estate.

Publications by Caffyn, Sheeran and Jowitt (1986– 1990) deal directly with workers houses in the 19th century. They provide many house plans, photographs and descriptions. They also describe the works of "model builders" and the aims of the "model housing" movement. All make reference to Ripley Ville but include no plans or photographs. Cafin's remit from the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments was to record extant buildings so such an absence is understandable: Ripley Ville had been demolished twenty years before the time of her survey. Sheeran and Jowitt probably had no good documentary evidence available. The location of Andrews and Pepper's archive, if it still exists, is unknown. The plans included in Ripley's prospectus and planning applications (Deposit Plans) held at Bradford library are no more than rough sketches. Absence of evidence may also account for the incorrect statements by Koditschek"[49] – that

"Ripley built 300 cottages to sell on mortgage to his workers.......When it became clear that the model dwellings were beyond the means of the majority of workers, a less ambitious scheme was implemented, providing cheaper units only marginally superior to existing housing in other working-class districts..... Ripley Ville disappeared as a distinctive community and remained only a name on a map"

In 2008 R.L Walker published a well researched booklet "When was Ripley Ville Built?". The booklet finally laid to rest Cudworth's incorrect dating. Using documents and copies of newspapers held at Bradford Library Walker established the dates and contents of Ripley's prospectus for the Ripley Ville houses, the grant of planning approval and issues of invitations to tender by Andrews and Pepper. This placed Ripley's initiative firmly in the context of the "bylaw revolt" and 1865 local elections. The expansion of the scheme to include a school and church were placed in the context of Henry Ripley's transition from local to national politician. One of the first events in the school (reported in the Bradford Observer) was a meeting in support of Ripley's candidature in the 1868 parliamentary election.

In 2011 R.L Walker established a website "Rediscovering Ripley Ville". The site has stimulated interest in the history of Ripley Ville and the dye works. Several of the "guest posts" are by former residents of Ripley Ville, who have provided copies of rare photographs. Some former residents had retained survey notes and measured drawings of the houses – details of which have been posted on the site. These are the source of the plans and section drawings shown in Fig. 6.

Another local history website "My West Bowling" has photographs of Ripley Ville and the surrounding area. The site also contains a series (1891–1934) of large scale (1:2500) Ordnance Survey Maps, available for viewing or download. These maps were marked up by Smith, Gotthard & Co. Land Agents and Surveyors to show land ownership boundaries (including Ripley's landholdings) and ownership changes. The 1911 maps are marked up to show the Midlands's through railway scheme described in "All Change".

Records and papers of Ripley' Dye Works and Ripley's Trustees are held at the West Yorkshire Archive, Wakefield. The WYA site provides an on line index to the collection

See also

- East Bowling

- Broomfields, Bradford

- Saltaire

- Ackroyden

- Bowling Ironworks

References

- Saltaire was not incorporated into the City of Bradford until the 1970s

- Jowitt (1986) includes descriptions of Saltaire, Copley, Ackroyden, West Hill Park, Wilshaw and Meltham Mills.

- Cudworth (1891), p. 247

- Cudworth (1891), p. 248

- Cudworth (1891), p. 257: "the enterprise and forsight of the late Sir Henry Ripley who erected .. many large blocks wholly devoted to the worsted industry"

- James Smith, Report on the Sanatory Condition of the Town of Bradford, Health of Towns Commission, 2nd Report, 1845, Vol. XVIII, Pt.2, p.315.

- George Sheeren.Back-to-back houses in Bradford. Bradford Antiquary 1986 in volume 2, pp. 47–53, of the third series.

- Cudworth (1882) – entries under the relevant years.

- Sheeran (1990), pp. 12–15

- Caffyn (1986), pp. 92–93

- Walker (2008), pp. 12–13

- Hole (1868)

- Caffyn (1986), chapter 8 "Improvement", pp. 82–106

- Walker (2008), pp. 13–15 sets out the planning approval and invitations to tender dates.

- Caffyn (1986), p. 89 reports that a plan for WC's in the Akroyden houses was dropped in view of the high water charges the Halifax Corporation demanded. Bradford Corporation bought Ripley's public supply water works in late 1866; this may have resulted in an increase in charges above the level Ripley's water works would have levied. The Corporation water works was desperately short of water in the 1860s and 1870s and discouraged the use of WC's. See Jowitt & Wright (1986), pp. 144–146.

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 14 December 1868 "Church building at Bradford". Leeds Mercury 12 December 1868 "Proposed New Church at Bowling"

- During construction the Thornton Railway Company was incorporated into the Great Northern Railway Company (GNR).

- Bradford Observer, 22 November 1866. p6 col 1 "the Rivers Commission"

- The Peadbody Islington Estate opened in 1865 had WCs. This may be the only example of provision of WCs in working class dwellings that predates Ripley Ville. The estate was of tenement blocks. Ten flats on each floor shared four WCs. For further details visit the Peabody Website at http://www.peabody.org.uk/media/2598/islington-archaeological-report-final-2012.pdf

- Cudworth (1977), p. 58; also quoted in Sheeran (1990), p. 30.

- Cf 1891, 1903 and 1912 1:2500 OS maps of Bowling." My west Bowling" web site.

- Caffyn (1986), p. 145

- Use of spaces are shown on the deposit plan held at West Yorkshire Archives Bradford. Building plan reference 4473/1-5.

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. 14 December 1868. "Church Building at Bradford"

- West Yorkshire Archives Bradford. Building Plan 6503/1-3, submitted 20 January 1871. The ground plan is identical to the As Built plan in ICBS archive.

- Bradford Observer Tuesday 11 April 1871. "St Bartholomew's Church:Laying the Foundation Stone"

- The Leeds Times 14 December 1872. Service of Consecration. The Memorial church of St Bartholomew's at Ripleyville.

- Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer - Wednesday 11 December 1872 p3 col3–5: Consecration of St Bartholomew's Church, Bradford

- Leeds Mercury, 25 August 1874 "Augmentation of Benefices"

- George Sheeran in " Brass Castles", pages 8–17, analyses the relationships between social class, wealth, income and house size and design in Victorian Bradford. St Bartholomew's Vicarage can be classed as a villa of the "affluent". Chapter 3 "The Workings of the House" provides exemplar plans of similar houses to the vicarage. The section " A room for Everything" describes the social assumptions behind design decisions

- Cudworth (1891), pp. 249–250

- Historic England. "Bowling Dyeworks Almshouses – 9/885 II (1132972)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- James Ledingham, 1849–1926. Born Aberdeen. Articled to A & W Reid of Elgin and Inverness in 1864. Assistant to Andrews & Pepper, Bradford 1870 to 1880. Commenced independent practice in 1880, initially at 53 Market Street, later at 1 New Ivegate. Passed RIBA qualifying exam in 1884; admitted ARIBA 1885 elevated to FRIBA 1892. He enjoyed a prosperous practice in Bradford, particularly in Manningham.

- West Yorkshire Archive, Bradford. Bradford Building Plan 11110/1-4

- Bradford Directory (2009), p. 138

- Benjamin Spencer was reported in the 1901 census as "grocer and beerseller" at "38 and 40 Linton Street"

- Bradford Observer, 4 November 1868 "Election Intelligence"

- Caffyn (1986), p. 78

- Bradford Observer 28 March 1874 Page 3 "The New Co-operative store at Ripleyville"

- Crockford's Clerical Directory 1896 lists Dr. A.B Cunningham as Vicar of Great St Mary's Cambridge (the University Church), Rural Dean of Cambridgeshire and Fellow of Trinity College

- Richardson (1976), pp. 56–59, esp. Fig. 14

- Thornhill (1986)

- Birmingham Daily Post 1 May 1900 "Heavy Arbitration Award"

- Rhodes (1890), pp. 57–70: "The Bradford Newspapers"

- David James "William Byles and the Bradford Observer" in "Victorian Bradford" (1982)

- Cudworth (1891), p. 249

- Bradford Centenary Yearbook, "Water Supply" and "Better Sanitation"

- "J.A. Jowitt and D. Wright(editors) "Victorian Bradford" page 1

- Koditschek. Class Formation and Urban Industrial Society in Bradford Page 433.

Bibliography

- Corporation, Bradford (1856). The Acts relating to the Transfer of the Bradford Waterworks to the Corporation of Bradford.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Directory, Bradford (2009) [1872]. Smiths Directory of Bradford 1872. Bank House Directories. ISBN 9781904408482.

- Directory, Bradford (2011) [1912]. Kelly's Directory of Bradford 1912. TWC Publishing.

- Caffyn, Lucy (1986). Worker's Houses in West Yorkshire 1750–1920. HMSO. ISBN 0-11-300002-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cudworth, William (1882). Historical Notes on the Bradford Corporation. Old Bradfordian Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cudworth, William (1888). Worstedopolis. Old General Books Memphis.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cudworth, William (1891). Histories of Bolton and Bowling. Bradford: Thomas Brear & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cudworth, William (1977) [1891]. Condition of the Industrial Classes. Collected articles from the Bradford Observer. Mountain Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Firth, Gary (2006). J. B. Priestley's Bradford. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-3865-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Firth, Gary (2001). Salt and Saltaire. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-1630-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hole, J. (1868). The Homes of the Working Classes with suggestions for their improvement. Longmans Green & Co. London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James, John (1967) [1841]. The History and Topography of Bradford. Longmans, republished by Mountain Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jowitt, J. A., ed. (1986). Model Industrial Communities in Mid Nineteenth Century Yorkshire. University of Bradford. ISBN 1-85143-016-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jowitt, J. A.; Wright, D. G., eds. (1986). Victorian Bradford. University of Bradford. ISBN 0-907734-01-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keighley, Mark (2007). Wool City. Whitaker and Company. ISBN 978-0-9555993-1-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Koditschek, Theodore (1990). Class formation and Urban Industrial Society Bradford 1750–1850. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521327717.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pickles, Derek (1966). The Bowling Tramways. Unpublished.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rhodes, J. F. (1890). Bradford Past and Present. J. F. Rhodes and Sons, Bradford.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richardson, C. (1976). A Geography of Bradford. University of Bradford. ISBN 0-901945-19-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scruton, William (1968) [1889]. Pen and Pencil Sketches of Old Bradford. Mountain Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheeran, George (1986). Good Houses Built of Stone. Allenwood Books. ISBN 0-947963-03-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheeran, George (1990). The Victorian Houses of Bradford. Bradford Libraries. ISBN 0-907734-21-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (First published in 1986 in volume 2, pp. 47–53, of the third series of The Bradford Antiquary, the journal of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society)

- Sheeran, George (1993). Brass Castles. Ryburn Publishing. ISBN 1-85331-022-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thornhill, John (1986). "All Change – Bradford's through railway scheme". Bradford Antiquary. 3rd. 2. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, R. L. (2008). When was Ripleyville Built?. SEQUALS. ISBN 0-9532139-2-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Observer, Yorkshire (1947). The Centenary Book of Bradford. YO, presented to Bradford Corporation.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ripley Ville. |

- Rediscovering Ripley Ville. http://www.rediscoveringripleyville.wordpress.com/

- My West Bowling http://sites.google.com/site/mywestbowling/home/

- West Yorkshire Archive Service. http://www.archives.wyjs.org.uk/archives-wakefield.asp

- Bradford Timeline Web Site. http://www.bradfordtimeline.co.uk/

- Bradford Society of Antiquaries http://www.bradfordhistorical.org.uk/antiquary/

- Newspapers http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

- ICBS Archive, Lambeth Palace Library https://web.archive.org/web/20170218143922/http://www.churchplansonline.org/

- Peabody Website http://www.peabody.org.uk/media