Riemann–Lebesgue lemma

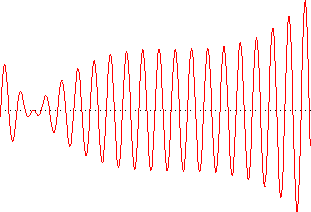

In mathematics, the Riemann–Lebesgue lemma, named after Bernhard Riemann and Henri Lebesgue, states that the Fourier transform or Laplace transform of an L1 function vanishes at infinity. It is of importance in harmonic analysis and asymptotic analysis.

Statement

If ƒ is L1 integrable on Rd, that is to say, if the Lebesgue integral of |ƒ| is finite, then the Fourier transform of ƒ satisfies

Proof

First suppose that , the indicator function of an open interval.

Then:

as

By additivity of limits, the same holds for an arbitrary step function. That is, for any function of the form:

We have that:

Finally, let be arbitrary.

Let be fixed.

Since the simple functions are dense in , there exists a simple function such that:

By our previous argument and the definition of a limit of a complex function, there exists such that for all :

By additivity of integrals:

By the triangle inequality for complex numbers, the [triangle inequality] for integrals, multiplicativity of the absolute value, and Euler's Formula:

For all , the right side is bounded by by our previous arguments. Since was arbitrary, this establishes:

for all .

Other versions

The Riemann–Lebesgue lemma holds in a variety of other situations.

- If ƒ is L1 integrable and supported on (0, ∞), then the Riemann–Lebesgue lemma also holds for the Laplace transform of ƒ. That is,

- as |z| → ∞ within the half-plane Re(z) ≥ 0.

- A version holds for Fourier series as well: if ƒ is an integrable function on an interval, then the Fourier coefficients of ƒ tend to 0 as n → ±∞,

- This follows by extending ƒ by zero outside the interval, and then applying the version of the lemma on the entire real line.

- A similar statement is trivial for L2 functions. To see this, note that the Fourier transform takes L2 to L2 and such functions have l2 Fourier series.

- However, the lemma does not hold for arbitrary distributions. For example, the Dirac delta function distribution formally has a finite integral over the real line, but its Fourier transform is a constant (the exact value depends on the form of the transform used) and does not vanish at infinity.

Applications

The Riemann–Lebesgue lemma can be used to prove the validity of asymptotic approximations for integrals. Rigorous treatments of the method of steepest descent and the method of stationary phase, amongst others, are based on the Riemann–Lebesgue lemma.

Proof

We'll focus on the one-dimensional case, the proof in higher dimensions is similar. Suppose first that ƒ is a compactly supported smooth function. Then integration by parts yields

If ƒ is an arbitrary integrable function, it may be approximated in the L1 norm by a compactly supported smooth function g. Pick such a g so that ||ƒ − g||L1 < ε. Then

and since this holds for any ε > 0, the theorem follows.

References

- Bochner S., Chandrasekharan K. (1949). Fourier Transforms. Princeton University Press.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Riemann–Lebesgue Lemma". MathWorld.

- https://proofwiki.org/wiki/Euler%27s_Formula