Richard Graves

Richard Graves (4 May 1715 – 23 November 1804) was an English cleric, poet, and novelist. He is remembered especially for his picaresque novel The Spiritual Quixote (1773).

Richard Graves | |

|---|---|

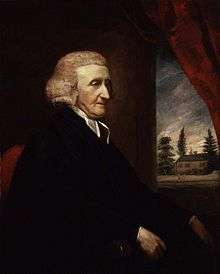

Richard Graves by James Northcote, 1799. | |

| Born | 4 May 1715 |

| Died | 23 November 1804 (aged 89) |

Early life

Graves was born at Mickleton Manor, Mickleton, Gloucestershire, to Richard Graves (1677–1729), an antiquary, and his Welsh wife Elizabeth, née Morgan.[1] Morgan Graves (died 1770) of the Inner Temple, and the cleric Charles Caspar Graves, were his brothers.[2][3][4]

Graves was educated first at a school run by William Smith, Curate at Mickleton from 1729, and then at John Roysse's Free School in Abingdon (now Abingdon School).[5] Smith's well-read daughter Utrecia later formed part of his life, a relationship he broke off before her death in 1743.[1][6]

Oxford don

Graves gained a scholarship at Pembroke College, Oxford, matriculating on 7 November 1732. George Whitefield was a servitor of Pembroke College, and they took their BA degree on the same day in July 1736. In the same year he was elected to a fellowship at All Souls College. Close for a time to Holy Club members, he retreated from the nascent Methodism of the group. He went to London to study medicine, attended the lectures of Dr Frank Nicholls on anatomy, but fell ill.[1][7] His brother Charles Caspar Graves, on the other hand, was for a time close to the Wesleys.[8]

Returning to Oxford, Graves took his master's degree in 1740, and was ordained. He was appointed to the curacy of Tissington in Derbyshire by William Fitzherbert of Tissington Hall, a colleague at the Inner Temple of his elder brother Morgan Graves. For three years Graves was the family chaplain at the Hall, where he rambled through the district later described in his major novel. After resigning this charge, he made a tour in the north, and at Scarborough met a distant relative, Samuel Knight, Archdeacon of Berkshire. Knight obtained for him the curacy of Aldworth, near Reading, Berkshire, where he was in residence in 1744. The parsonage was out of repair, so that he lived in the house of a gentleman farmer, Mr Bartholomew of Dunworth, whose daughter he married.[1][7]

Graves's marriage meant that he automatically ceased to be a Fellow of All Souls in January 1749.[7][9]

Later life

For a period, Graves was short of money. Through the interest of Sir Edward Harvey of Langley, near Uxbridge, he was presented in 1748 by William Skrine as rector of Claverton, near Bath, Somerset. He was inducted in July 1749, came into residence in 1750, and until his death never left the living for long.[7]

Ralph Allen obtained for Graves in 1763 the adjoining vicarage of Kilmersdon, and also found him an appointment as chaplain to Mary Townshend, Countess Chatham. About 1793 he took the rectory of Croscombe, also in Somerset, but held it temporarily. He purchased the advowson of Claverton from Allen's representatives in 1767, but later resold it to them. The old rectory house had been built in part by Allen in 1760, but it was enlarged by Graves.[7]

Graves for 30 years took pupils, whom he educated with his own children. Until his parsonage house was enlarged he rented from Mrs. Warburton for sixty pounds a year the large house at Claverton, and "the great gallery-library was turned into a dormitory". Through his preferments and teaching he gradually prospered, and among his purchases was the manor of Combe in Combe Monckton, Somerset. He reportedly, at nearly 90, walked almost daily to Bath. He was a Whig in politics, who mixed widely in society, was a frequent guest of Allen or the Warburtons at Prior Park, and "contributed to the vase", taking part in the literary circle at Anna, Lady Miller's house at Batheaston. Shenstone paid him repeated visits at Claverton, between 1744 and 1763.[7]

Graves died on 23 November 1804, and was buried in the parish church on 1 December. A mural tablet was placed there to his memory.[7]

Associations

Among Graves's college friends were William Blackstone, Richard Jago, William Hawkins: and William Shenstone, who became a close friend. Graves later wrote Recollections of Shenstone. The fourth elegy by Shenstone is Ophelia's Urn. To Mr. G—— (i.e. Graves), and the eighth elegy is also addressed To Mr. G——, 1745. Letters from Shenstone to Graves are in vol. iii. of the former's Works; a letter addressed to Mr. —— on his marriage, written 21 August 1748, may refer to Graves. In the Works, ii. 322–3, are "To William Shenstone at the Leasowes by Mr. Graves",’ and "To Mr. R. D. on the death of Mr. Shenstone", signed "R. G."[7]

At Tissington Hall, Graves made the acquaintance of Charles Pratt, Sir Edward Wilmot, Nicholas Hardinge, and other notable persons. He served as private tutor to Prince Hoare and Thomas Malthus. He was a close friend of Anthony Whistler, Ralph Allen, and William Warburton; Ralph Allen Warburton, the bishop's only son, and author Henry Skrine of Warleigh, were other pupils. Shenstone's letter to Graves on the death of Anthony Whistler was among the manuscripts of Alfred Morrison.[7]

Works

Graves was a collector of poems, a translator, essayist and correspondent.[7]

The Spiritual Quixote

Graves's major work is the picaresque novel, The Spiritual Quixote (1773). It a satire on John Wesley, George Whitefield, and Methodism in general, which he saw as a threat to his Anglican congregation.[10]

The book's full title was The Spiritual Quixote, or the Summer's Ramble of Mr. Geoffry Wildgoose, a Comic Romance (anon.), 1772, 1773, 1774 (two editions), 1783, and 1808. It was in Anna Barbauld's collection British Novelists, and in Walker's British Classics. It ridiculed the intrusion of the laity into spiritual functions and the enthusiasm of the Methodists.[7]

The hero has been identified with Sir Harry Trelawny, 5th Baronet (unlikely by chronology), Joseph Townsend and his own brother Charles Caspar Graves. The novel is said to have arisen out of the arrival in the parish of Claverton of a shoemaker from Bradford-on-Avon, who held a meeting in the village. The rambles in the novel brought Wildgoose to Bath, Bristol, the Leasowes of Shenstone, and the Peak District. A key to several of the personages was supplied by Alleyne Fitzherbert to John Wilson Croker. Graves's own love life was portrayed in vol. ii.[7]

Other works

Graves from early life wrote verses for magazines, and some of his poems appeared in the collections of Robert Dodsley (iv. 330–7) and George Pearch (iii. 133–8). He also wrote several plays, while his prose works were popular in his day. He published:[7]

- The Festoon; a Collection of Epigrams (anon.), 1766 and 1767

- Galateo, or a Treatise on Politeness, translated from Il Galateo overo de’ costumi of Giovanni della Casa, 1774

- The Love of Order; a Poetical Essay, in three cantos (anon.), 1773. Dedicated to William James of Denford, Berkshire

- Euphrosyne; or Amusements on the Road of Life, 1776; 3rd edition vol. i. 1783; 2nd edition vol. ii. 1783, with appendix of pieces written for the Poetical Society at Batheaston

- Columella; or the Distressed Anchoret, a Colloquial Tale, 1779. In praise of an active life as superior to that of a small country gentleman, and possibly suggested by the career of Shenstone

- Eugenius; or Anecdotes of the Golden Vale (anon.), 1785, 2 vols. A tale of life in a Welsh valley

- Lucubrations, consisting of Essays, Reveries, &c., by the late Peter of Pontefract, 1786

- Recollections of some particulars in the Life of the late William Shenstone, in a Series of Letters from an intimate Friend of his [i.e. Graves] to … esq., F.R.S. [William Seward], 1788

- The Rout; or a Sketch of Modern Life, from an Academic in the Metropolis to his Friend in the Country, 1789

- Plexippus; or the Aspiring Plebeian (anon.), 1790, 2 vols.

- Fleurettes; a translation of Fénelon's "Ode on Solitude".

- Meditations of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, a new translation from the Greek original, with a Life, Notes, &c., by R. Graves, 1792; new edition, Halifax, 1826; from the Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

- Hiero on the Condition of Royalty, a Conversation from the Greek of Xenophon, by the Translator of Antoninus, 1793

- The Heir-Apparent, or the Life of Commodus, from the Greek of Herodian, with a preface adapted to the present time, 1789

- The Reveries of Solitude, consisting of Essays in Prose, a new translation of the "Muscipula", and Original Pieces in Verse, 1793

- The Coalition; or the Opera Rehearsed, a Comedy in three acts, 1794. This work included Echo and Narcissus, a dramatic pastoral which originally appeared in Euphrosyne, vol. ii

- The Farmer's Son; a Moral Tale, by the Rev. P. P., M.A., 1795

- Sermons, with A Letter from a Father to his Son at the University, Bath, 1799

- Senilities, or Solitary Amusements in Prose and Verse, with a Cursory Disquisition on the Future Condition of the Sexes, by the Editor of the "Reveries of Solitude", 1801

- The Invalid, with the Obvious Means of Enjoying Health and Long Life, by a Nonagenarian, editor of the "Spiritual Quixote," 1804; dedicated to Prince Hoare

- The Triflers, consisting of Trifling Essays, Trifling Anecdotes, and a few Poetical Trifles, to which are added "The Rout" and "The Farmer's Son." By the late Rev. R. Graves, 1805

Graves wrote the 30th number, on "grumbling", in Thomas Monro's Olla Podrida In the Gentleman's Magazine, 1815, pt. ii. p. 3, are some Lines written by him under an hour-glass in the grotto at Claverton.[7]

Family

Graves married Lucy Bartholomew (died 1777), a farmer's daughter from Aldworth, after eloping to London with her around the end of 1746, in August 1747; she bore him a son, Richard, shortly. She had been baptised in 1730, and was uneducated; he had sent her to a private school in London before the marriage.[1] His friends did not immediately accept his marriage, but came round to it.[11]

The couple had four sons and a daughter.[1] Their son Richard Charles Head Graves was vicar of Great Malvern.[12][13] Two other sons were Morgan and Danvers.[14]

See also

References

- Oakleaf, David. "Graves, Richard (1715–1804)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11313. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- s:Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715-1886/Graves, Morgan (1)

- s:Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715-1886/Graves, Charles (Gasper)

- Persons: Graves, Charles Caspar (1740–1787) in "CCEd, the Clergy of the Church of England database" (Accessed online, 23 April 2017)

- "Object 6: Portrait of Thomas Tesdale". Abingdon School.

- Persons: Andrewes, Lancelot (1729–1729) in "CCEd, the Clergy of the Church of England database" (Accessed online, 23 April 2017)

- Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney, eds. (1890). . Dictionary of National Biography. 22. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- "Galland – Gwyther (The University of Manchester Library)". Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- All Souls College, History of the College: Victorian Reform

- Quoted in Hill, C.J. (1935) "The Literary Career of Richard Graves, the Author of The Spiritual Quixote." Smith College Studies in Modern Languages XVI.1–3. 18.

- Marjorie Williams (1946). Lady Luxborough Goes to Bath. B. Blackwell. p. 42.

- in The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21), Volume X. The Age of Johnson. XI. Letter-Writers. §22. Richard Graves and his literary work.

- Debrett, John (1822). Scotland and Ireland. G. Woodfall. p. 1238. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- s:Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715-1886/Graves, Rev. Richard

Further reading

- Tracy, C (1987) A Portrait of Richard Graves ISBN 0-8020-5697-0

- Hill, CJ (1935) "The Literary Career of Richard Graves, the Author of The Spiritual Quixote." Smith College Studies in Modern Languages XVI.1–3

External links

Attribution

![]()