Richard Gerstl

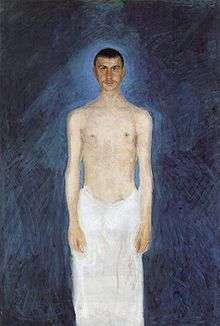

Richard Gerstl (14 September 1883 – 4 November 1908) was an Austrian painter and draughtsman known for his expressive psychologically insightful portraits, his lack of critical acclaim during his lifetime, and his affair with the wife of Arnold Schoenberg which led to his suicide.

Richard Gerstl was born in a prosperous civil family, to Emil Gerstl, a Jewish merchant, and Maria Pfeiffer, non-Jewish woman.[1]

Early in his life, Gerstl decided to become an artist, much to the dismay of his father. After performing poorly in school and being forced to leave the famed Piaristengymnasium in Vienna as a result of "disciplinary difficulties," his financially stable parents provided him with private tutors. In 1898, at the age of fifteen, Gerstl was accepted into the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, where he studied under the notoriously opinionated and difficult Christian Griepenkerl. Gerstl began to reject the style of the Vienna Secession and what he felt was pretentious art. This eventually prompted his vocal professor to proclaim, "The way you paint, I piss in the snow!"

Frustrated with the lack of acceptance of his non-secessionist painting style, Gerstl continued to paint without any formal guidance for two years. For the summers of 1900 and 1901, Gerstl studied under the guidance of Simon Hollósy in Nagybánya. Inspired by the more liberal leanings of Heinrich Lefler, Gerstl once again attempted formal education. Unfortunately, his refusal to participate in a procession in honor of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria further ostracized him and led to his departure. Gerstl felt that taking part in such an event was "unworthy of an artist." His final exit from Lefler's studio took place in 1908.

In 1904 and 1905, Gerstl shared a studio with his former academy classmate and friend, Viktor Hammer. Although Hammer had assisted in Gerstl's admittance to Lefler's tutelage and their relationship was friendly, it is difficult to determine how close the two men were as Gerstl did not associate with other artists. Regardless of their personal feelings, by 1906, Gerstl had acquired his own studio.

Art

Gerstl was a pioneer of Austrian Expressionism. An exhibition from 7 through 14 July 1907 at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna is the only known exhibition of his work that occurred during his lifetime. He was radically opposed to and rejected contemporary art practice, namely that of the Jugendstil and Gustav Klimt. He belonged for many years, as a young artist, to the so-called Schoenberg Circle. His proximity to the Viennese avant-garde was appreciable.

His works were rediscovered in the early 1930s, and their significance was recognized after 1945. Nevertheless, to this day little is known of this representative of the Austrian Expressionists. Sixty of his paintings and 8 drawings, most of which are in the Leopold Museum and the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, are known to be extant.

Alois Gerstl, brother of Richard, found canvases and sketches in the artist's atelier, which he left for many years with a forwarding agent. Ultimately, thirty-four paintings were saved from destruction by Otto Kallir, a gallery owner. Kallir bought and restored the paintings, and his 1931 exhibition Richard Gerstl -- A Painter's Destiny caused quite a stir. The exhibition would later appear in Munich, Berlin, and Aachen. He became a key figure for the Austrian art scene, inspiring artists of the post-war era, even still in the time of Viennese Actionism. Since the 1980s, with the inclusion of his work in exhibitions of art from turn-of-the-century Vienna, Gerstl has been recognized in the canon of art history.

The Kamm Collection (Stiftung Sammlung Kamm) of the art gallery Kunsthaus Zug in Zug, Switzerland possesses ten of Gerstl's paintings on eight canvases. They include landscapes and a variety of portraits.

Arnold Schoenberg

Although Gerstl did not associate with other artists, he did feel drawn to the musically inclined; he himself frequented concerts in Vienna. Around 1907, he began to associate with composers Arnold Schoenberg and Alexander von Zemlinsky, who lived in the same building at the time. Gerstl and Schoenberg developed a mutual admiration based upon their individual talents. Gerstl apparently instructed Schoenberg in art.[2]

During this time, Gerstl moved into a flat in the same house and painted several portraits of Schoenberg, his family, and his friends. These portraits also included paintings of Schoenberg's wife Mathilde, Alban Berg and Zemlinsky. His highly stylized heads anticipated German expressionism and used pastels as in the works by Oskar Kokoschka. Gerstl and Mathilde became extremely close and, in the summer of 1908, she left her husband and children to travel to Vienna with Gerstl. Schoenberg was in the midst of composing his Second String Quartet, which he dedicated to her. Mathilde rejoined her husband in October.[2]

Distraught by the loss of Mathilde, his isolation from his associates, and his lack of artistic acceptance, Gerstl entered his studio during the night of 4 November 1908 and apparently burned every letter and piece of paper he could find.[2] Although many paintings survived the fire, it is believed that a great deal of his artwork as well as personal papers and letters were destroyed. Other than his paintings, only eight drawings are known to have survived unscathed. Following the burning of his papers, Gerstl hanged himself in front of the studio mirror and somehow managed to stab himself as well.

The incident had a significant impact on Arnold Schoenberg and his "drama with music" (i.e., opera) Die glückliche Hand is based on these events.

After his suicide at the age of twenty-five, his family took the surviving paintings out of Gerstl's studio and stored them in a warehouse until his brother Alois showed them to the art dealer Otto Kallir in 1930 or 1931. Although Gerstl had never managed to exhibit a show during his lifetime, Kallir organized an exhibition at his Neue Galerie. Shortly afterward, the Nazi presence in Austria hindered the further acclaim of the artist and it was not until after the war that Gerstl was known in the United States. Sixty-six paintings and eight drawings attributed to Gerstl are known, although it is possible he destroyed many more or that others could have been lost over the years.

Bibliography

- Stefan Üner: Richard Gerstl. Früh vollendet, spät entdeckt, in: Parnass, 3/2019, p. 118–124.

References

- Hans Morgenstern "Jüdisches Biographisches Lexikon", Lit Verlag

- H. H. Stuckenschmidt, Schoenberg: His Life, World and Work (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1977), p. 93-97.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richard Gerstl. |

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richard Gerstl. |