Retinotopy

Retinotopy (from Greek τόπος, place) is the mapping of visual input from the retina to neurons, particularly those neurons within the visual stream. For clarity, 'retinotopy' can be replaced with 'retinal mapping', and 'retinotopic' with 'retinally mapped'.

Visual field maps (retinotopic maps) are found in many mammalian brains, though the specific size, number, and spatial arrangement of these maps can differ considerably between species.

Retinotopic maps in cortical areas other than V1 are typically more complex, in the sense that adjacent points of the visual field are not always represented in adjacent regions of the same area. For example, in the second visual area (V2), the map is divided along an imaginary horizontal line across the visual field, in such a way that the parts of the retina that respond to the upper half of the visual field are represented in cortical tissue that is separated from those parts that respond the lower half of the visual field. Even more complex maps exist in the third and fourth visual areas V3 and V4, and in the dorsomedial area (V6). In general, these complex maps are referred to as second-order representations of the visual field, as opposed to first-order (continuous) representations such as V1.[1] Additional retinotopic regions include ventral occipital (VO-1, VO-2),[2] lateral occipital (LO-1, LO-2),[3] dorsal occipital (V3A, V3B),[4] and posterior parietal cortex (IPS0, IPS1, IPS2, IPS3, IPS4).[5]

History

The discovery of visual field maps in humans can be traced to neurological cases, arising from war injuries, described and analyzed independently by Tatsuji Inouye (a Japanese ophthalmologist) and Gordon Holmes (a British neurologist). They observed correlations between the position of the entry wound and visual field loss (see Fishman, 1997[6] for an historical review).

Description

In many locations within the brain, adjacent neurons have receptive fields that include slightly different, but overlapping portions of the visual field. The position of the center of these receptive fields forms an orderly sampling mosaic that covers a portion of the visual field. Because of this orderly arrangement, which emerges from the spatial specificity of connections between neurons in different parts of the visual system, cells in each structure can be seen as contributing to a map of the visual field (also called a retinotopic map, or a visuotopic map). Retinotopic maps are a particular case of topographic organization. Many brain structures that are responsive to visual input, including much of the visual cortex and visual nuclei of the brain stem (such as the superior colliculus) and thalamus (such as the lateral geniculate nucleus and the pulvinar), are organized into retinotopic maps, also called visual field maps.

Areas of the visual cortex are sometimes defined by their retinotopic boundaries, using a criterion that states that each area should contain a complete map of the visual field. However, in practice the application of this criterion is in many cases difficult.[1] Those visual areas of the brainstem and cortex that perform the first steps of processing the retinal image tend to be organized according to very precise retinotopic maps. The role of retinotopy in other areas, where neurons have large receptive fields, is still being investigated.[7]

.jpg)

Retinotopy mapping shapes the folding of the cerebral cortex. In both the V1 and V2 areas of macaques and humans the vertical meridian of their visual field tends to be represented on the cerebral cortex's convex gyri folds whereas the horizontal meridian tends to be represented in their concave sulci folds.[8]

Methods

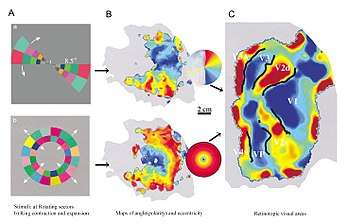

Retinotopy mapping in humans is done with functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI). The subject inside the fMRI machine focuses on a point. Then the retina is stimulated with a circular image or angled lines about focus point.[9][10][11] The radial map displays the distance from the center of vision. The angular map shows angular location using rays angled about the center of vision. Combining the radial and angular maps, you can see the separate regions of the visual cortex and the smaller maps in each region.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Retinotopy. |

- Biological neural network

- Cortical magnification

- Frontal eye field

- Tonotopy

- Visual space

References

- Rosa MG (December 2002). "Visual maps in the adult primate cerebral cortex: some implications for brain development and evolution". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research = Revista Brasileira de Pesquisas Medicas e Biologicas. 35 (12): 1485–98. doi:10.1590/s0100-879x2002001200008. PMID 12436190.

- Brewer AA, Liu J, Wade AR, Wandell BA (August 2005). "Visual field maps and stimulus selectivity in human ventral occipital cortex". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (8): 1102–9. doi:10.1038/nn1507. PMID 16025108.

- Larsson J, Heeger DJ (December 2006). "Two retinotopic visual areas in human lateral occipital cortex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (51): 13128–42. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1657-06.2006. PMC 1904390. PMID 17182764.

- Tootell RB, Mendola JD, Hadjikhani NK, Ledden PJ, Liu AK, Reppas JB, Sereno MI, Dale AM (September 1997). "Functional analysis of V3A and related areas in human visual cortex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 17 (18): 7060–78. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-07060.1997. PMC 6573277. PMID 9278542.

- Silver MA, Ress D, Heeger DJ (August 2005). "Topographic maps of visual spatial attention in human parietal cortex". Journal of Neurophysiology. 94 (2): 1358–71. doi:10.1152/jn.01316.2004. PMC 2367310. PMID 15817643.

- Ronald S. Fishman (1997). Gordon Holmes, the cortical retina, and the wounds of war. The seventh Charles B. Snyder Lecture Documenta Ophthalmologica 93: 9-28, 1997.

- Wandell BA, Brewer AA, Dougherty RF (April 2005). "Visual field map clusters in human cortex". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 360 (1456): 693–707. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1628. PMC 1569486. PMID 15937008.

- Rajimehr R, Tootell RB (September 2009). "Does retinotopy influence cortical folding in primate visual cortex?". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (36): 11149–52. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1835-09.2009. PMC 2785715. PMID 19741121.

- Bridge H (March 2011). "Mapping the visual brain: how and why". Eye. 25 (3): 291–6. doi:10.1038/eye.2010.166. PMC 3178304. PMID 21102491.>

- DeYoe EA, Carman GJ, Bandettini P, Glickman S, Wieser J, Cox R, Miller D, Neitz J (March 1996). "Mapping striate and extrastriate visual areas in human cerebral cortex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (6): 2382–6. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.2382D. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.6.2382. PMC 39805. PMID 8637882.

- Engel SA, Glover GH, Wandell BA (March 1997). "Retinotopic organization in human visual cortex and the spatial precision of functional MRI". Cerebral Cortex. 7 (2): 181–92. doi:10.1093/cercor/7.2.181. PMID 9087826.