Repertoire of contention

Repertoire of contention refers, in social movement theory, to the set of various protest-related tools and actions available to a movement or related organization in a given time frame.[1][2]

Description

Repertoires are often shared between social actors; as one group (organization, movement, etc.) finds a certain tool or action successful, in time, it is likely to spread to others.[1][2] However, in addition to providing options, repertoires can be seen as limiting, as people tend to focus on familiar tools and actions, and innovation outside their scope is uncommon (see diffusion of innovations).[1][3]

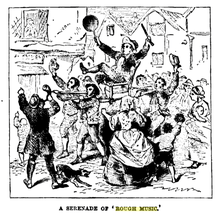

Actions and tools that belong to common repertoires of contention include, but are not limited to: creation of special-purpose associations and coalitions, public meetings, solemn processions, vigils, rallies, demonstrations, sit-ins, petition drives, statements to and in public media, boycotts, strikes and pamphleteering. Repertoires change over time, and can vary from place to place.[2][3] They are determined both by what the actors know how to do, and what is expected from them.[3] Early repertoires, from the time before the rise of the modern social movement, included food riots and banditry.[2] The changing nature of repertoires of contention can be seen in a sample element of the mid-18th century British repertoire of contention, the rough music: a humiliating and loud public punishment inflicted upon one or more people who have violated the standards of the rest of the community.[4] For yet another example, consider that in the recent years, Internet-focused repertoires have been developed (see hacktivism).[1] Recent scholarship has introduced a notion that in addition to the "traditional" and "modern" repertoires, a new, "digital", repertoire may be emerging.[5] In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic modes of contention at the intersection of physical and digital evolved, described by Yunus Berndt as peopleless protests.[6]

While the term is used most often in the social movement theory context, it can be applied to any political actors.[7] Repertoires of contention also existed before the birth of the modern social movement (a period most scholars identify as the late 18th to early 19th century).[3]

The term is attributed to Charles Tilly.[1][3]

References

- Brett Rolfe, Building an Electronic Repertoire of Contention. Social Movement Studies,Vol. 4, No. 1, 65–74, May 2005

- David A. Snow; Sarah Anne Soule; Hanspeter Kriesi (2004). The Blackwell companion to social movements. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 300–. ISBN 978-0-631-22669-7. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- Sidney G. Tarrow (1998). Power in movement: social movements and contentious politics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-521-62947-8. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- Charles Tilly (2003). The politics of collective violence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-0-521-53145-0. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- Jennifer Earl; Katrina Kimport (31 March 2011). Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in the Internet Age. MIT Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-262-01510-3. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- "Peopleless Protest: Standing up for Refugee Rights Despite the Covid-19 Lockdown | Responsibility". RESET.to. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- Charles Tilly (2002). Stories, identities, and political change. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-0-7425-1882-7. Retrieved 22 January 2011.