Renkioi Hospital

Renkioi Hospital was a pioneering prefabricated building made of wood, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel as a British Army military hospital for use during the Crimean War.

Background

During 1854 Britain entered into the Crimean War, and the old Turkish Selimiye Barracks in Scutari became the British Army Hospital. Injured men contracted illnesses—including cholera, dysentery, typhoid and malaria—due to poor conditions there.[1] After Florence Nightingale sent a plea to The Times for the government to produce a solution, the British government were alarmed by the revelation of the appalling state and statistics of military hospitals in the first phase of the war.

Design

In February 1855, Isambard Kingdom Brunel was invited by the Permanent Under Secretary at the War Office, Sir Benjamin Hawes (husband of his sister Sophia), to design a pre-fabricated hospital for use in the Crimea, that could be built in Britain and shipped out for speedy erection at a still-to-be-chosen site.[2]

Brunel initially designed a unit ward to house 50 patients, 90 feet (27 m) long by 40 feet (12 m) wide, divided into two hospital wards. The design incorporated the necessities of hygiene: access to sanitation, ventilation, drainage, and even rudimentary temperature controls.[3] These were then integrated within a 1,000-patient hospital layout, using 60 of the unit wards.[4] The design took Brunel six days in total to complete.[5]

Fabrication

From 1849 Gloucester Docks-based timber merchants Price & Co. became involved in supplying wood to local contractor William Eassie, who was supplying railway sleepers to the Gloucester and Dean Forest Railway. Eassie's company diversified after the railway boom period, manufacturing windows and doors, as well as prefabricated wooden huts to the gold prospectors in Australia.[4] As a result, when the Government wanted to provide shelter to the soldiers in the Dardanelles, Price & Co. chairman Richard Potter had tendered to supply Eassie design as a solution, and gained a 500-unit order.[4] Potter then travelled to France and obtained an order from the French Emperor for a further 1,850 huts to a slightly modified design.

French Army soldiers arrived in Gloucester Docks in December 1854 to learn how to erect the huts. Supply was delayed by the need to transfer the resultant packs from broad-gauge GWR to standard-gauge LSWR tracks, with the last packs shipped from Southampton Docks in January 1855.[4]

Having worked with Eassie on creating the slipway for the SS Great Eastern,[6] Brunel approached Price & Co. about producing the 1,000-patient hospital. The last of the units was shipped from Southampton on one of 16 ships, less than five months later.[4][7]

Construction

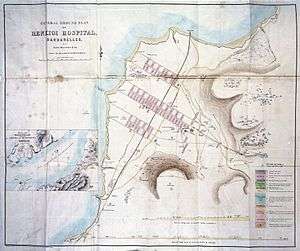

In January 1855, the Government had selected Dr Edmund Alexander Parkes to travel to Turkey to select a site for the hospital, organise the facility, and superintend the whole operation. Parkes had selected Erenköy on the Asiatic bank of the Dardanelles near the fabled city of Troy. This was located 500 miles (800 km)—then three or four days' journey—from the Crimea, but importantly outside the malaria zone in which Scutari was located.[8] Parkes remained on-site until the end of the war in 1856.[9]

After William Eassie Snr had seen the awful state of construction of the previously shipped British Army huts at Balaklava, he sent his son to supervise the construction of the hospital.[4] The whole kit of parts had reached the site by May 1856, and by July was ready to admit its first 300 patients. Although hostilities had ceased in April, by December it had reached its capacity of 1,000 beds,[5] scheduled to expand to 2,200.[3]

Management and operations

Renkioi was designated a civilian hospital, under the War Office but independent of the Army Medical Department, and hence outside the management of Florence Nightingale. It had a nursing staff selected by Parkes and Sir James Clark, including as a volunteer Parkes's sister;[10] while other staff included Dr John Kirk, later of Zanzibar fame.

Run as a model hospital, it "demonstrated the best practices of the age". This was in contrast to the Army medical facilities, which between them had two clinical thermometers and one ophthalmoscope. Also, despite the Royal Navy's success in preventing scurvy through the provision of concentrated fruit juice, the army failed to learn the same lesson, and so its Crimean soldiers suffered from scurvy.

Renkioi Hospital however had a short life. It received its first casualties in October 1855, after the fall of Sevastopol, was closed in July 1856, and was sold to the Ottoman Empire in September 1856.[11]

But even for such short used institutions, it was feted as a great success. Sources state that of the approximately 1,300 patients treated in the hospital, there were only 50 deaths.[12] In the Scutari hospital, deaths were said to be as many as 10 times this number.[3] Nightingale referred to them as "those magnificent huts".[13]

Present

Today almost nothing survives from it, although regular tourist trips do take in the site.

The practice of building hospitals from prefabricated modules survives today,[8] with hospitals such as the Bristol Royal Infirmary being created in this manner.

Notes

- "Report on Medical Care". British National Archives (WO 33/1 ff.119, 124, 146–7). Dated 23 February 1855.

- "Prefabricated wooden hospitals". British National Archives (WO 43/991 ff.76–7). Dated 7 September 1855.

- "Renkioi Hospital". New Civil Engineer. 12 October 2000. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- "William Eassie – notable Victorian contractor". Gloucester Society for Industrial Archeology. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- "The 1840s and 1850s". brunel200.com. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- Parsons, Brian. "Eassie, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/98214. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Buchanan, R. Angus. "Brunel, Isambard Kingdom". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3773. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Lessons from Renkioi" (at the Internet Archive). Hospital Development Magazine. 10 November 2005. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- John A. Shepherd, The Crimean Doctors: a history of the British medical services in the Crimean War, vol. 1 (1991), p. 441; Google Books.

- Dr Christopher Silver RAMC (2007). Renkioi: Brunel's Forgotten Crimean War Hospital. Valonia Press. ISBN 978-0-9557105-0-6.

- "Palmerston, Brunel and Florence Nightingale’s Field Hospital" (PDF). HMSwarrior.org. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- "Britain's Modern Brunels". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

References

- Dr Christopher Silver RAMC (2007). Renkioi: Brunel's Forgotten Crimean War Hospital. Valonia Press. ISBN 978-0-9557105-0-6.