Reginald Piggott

Reginald "Reg" Piggott (1930 – c. 2014) was a British book cartographer whose maps were known for their elegance, clarity, and distinctive italic script. His work was published by Cambridge University Press and The Folio Society among other presses. Early in his life, he was a campaigner for better handwriting and in 1957 organised a survey of British handwriting which drew over 25,000 responses and was subsequently published in book form. He advocated the use of a form of italic script to replace the civil service script widely used in Britain which he thought tended to illegibility when written at speed.

Early life and family

Reginald Piggott was born in 1930.[1] He married Marjorie. He was a long time resident of Decoy Lodge, Decoy Road, Potter Heigham, Norfolk.

Handwriting survey

In February 1957,[2] eleven newspapers and journals published a letter from Reginald Piggott of 10 Finlay Drive, Dennistoun, Glasgow, in which he requested samples of handwriting. By far the greatest response came from readers of The Observer whose readers sent him 15,000 samples of their writing. In an article in that paper in March 1957, Piggott explained that he had been interested in the history of handwriting since he had begun to study calligraphy and that he wished to develop a "practical, everyday cursive" script to replace the civil service style then in use in Britain that was derived from Victorian copperplate writing but which tended to illegibility when written at speed. By gathering samples of handwriting, he hoped to develop a new style that would command widespread acceptance. He made clear that he was not a graphologist and was not offering insights into the character of the writer.[3]

Piggott envisaged a simplified script that dispensed with loops and flourishes and reduced letter forms to as fundamental a shape as possible. In a running script, joins were to be made in the simplest manner. He went on to discuss the beauty of italic script, which he used in his own writing, and the unsuitability of the ball point pen to produce it before concluding that once his research was complete "and it is certain that the new style is near perfect", then it could be widely adopted, leading to a great improvement in the handwriting of the nation.[3]

The results of the survey were published in 1958 as Handwriting: A national survey, together with a plan for better modern handwriting by which time Piggott had acquired over 25,000 samples of handwriting.[4][5] He analysed the results of his survey according to multiple characteristics including sex, age and occupation, and concluded with a chapter outlining a plan for better modern writing using a form of italic script.[6][7] Writing in the New Scientist, Gail Vines placed Piggott's research and the public's enthusiasm for the project in the context of rapid social and technological change in the 1950s that resulted in a moral panic about declining standards of penmanship that reflected a generalised anxiety about threats to standards in a changing world.[8]

Cartography

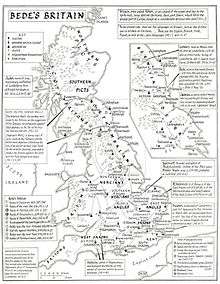

Piggott's cartography was known for its clarity and elegance which was aided by his distinctive italic lettering. In 2014, the travel writer Nicholas Crane described him as "the most brilliant book-cartographer of our generation".[9]

He produced numerous maps for Cambridge University Press,[10] and had a long association with The Folio Society for whose books he produced many works, including a double page map of the spread of the Great Fire of London which was included in their volume on that subject published in 2003. He prepared the maps for The Oxford Illustrated History of Britain (1984) and with his wife Marjorie for volumes of Nikolaus Pevsner's The Buildings of England.

In 2012, Aurum Press published Mile by mile London to Paris in which the route between the cities was mapped out by Piggott with a text by Matt Thompson, assuming a journey by the Golden Arrow, when it existed, and the Eurostar more recently.

Selected publications

- Practical handwriting. Blackie & Son, London & Glasgow, 1955.

- Handwriting: A national survey, together with a plan for better modern handwriting. Allen & Unwin, London, 1958.

- Mile by mile London to Paris: The entire route by historic Golden Arrow and modern Eurostar. Aurum, 2012. (With Matt Thompson) ISBN 978-1845137724

References

- British Library catalogue. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "Handwriting", Reginald Piggott, Letters to the Editor, The Observer, 17 February 1957, p. 2.

- "Handwriting To-morrow", Reginald Piggott, The Observer, 10 March 1957, pp. 10 & 12. ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Retrieved 4 July 2016. (subscription required)

- Hensher, Philip. (2012). The Missing Ink: How Handwriting Made Us Who We Are. Macmillan. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-230-76736-2.

- Sassoon, Rosemary. (2007). Handwriting of the Twentieth Century. Bristol: Intellect Books. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-84150-178-9.

- "Handwriting: A national survey", Linton Godown, The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science, Vol. 49, No. 6 (Mar.- Apr., 1959), pp. 625-626.

- "On Italic Handwriting", Frank N. Freeman, The Elementary School Journal, Vol. 60, No. 5 (Feb., 1960), pp. 258-264.

- "The big scribble", Gail Vines, New Scientist, 25 June 2005, p. 54.

- "Cartographers: Masters of omission" by Nicholas Crane in Folio, March 2014, pp. 37-41.

- Maps of Anglo-Saxon England. Kemble: The Anglo-Saxon Charters Website. Retrieved 22 April 2016.