Red Spears' uprising in Shandong (1928–1929)

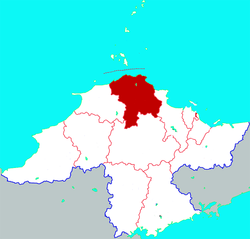

The Red Spear Society staged a major uprising in 1928–1929 against the rule of Liu Zhennian, the Nationalist government-aligned warlord ruler of eastern Shandong province in Republican China. Motivated by their resistance against high taxes, rampant banditry and the brutality of Liu's private army, the Red Spear peasant insurgents captured large areas on the Shandong Peninsula and were able to set up a proto-state in Dengzhou county. Despite this, the whole insurgency was eventually crushed by Liu in late 1929.

| Red Spears' uprising in Shandong | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Red Spear Society | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Liu Zhennian | Regional leaders | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| Village militias | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000–30,000[2] | 50,000–60,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Low | High | ||||||

| High civilian casualties | |||||||

Background

The Red Spear Society was a movement and network of peasant self-defense and vigilante militias that sprung up throughout China in response to the chaos of the Warlord Era in the 1910s and 1920s. As the influence of the Red Spears grew, branches of the movement were set up in several Chinese provinces, such as Shandong. The largest area of Red Spears activity in Shandong was its western counties, while the Shandong Peninsula in the east remained relatively calm until the late 1920s. The only eastern area with a large Red Spears presence was Laiyang county.[5][6]

This changed in fall of 1928, as banditry on the peninsula rapidly increased, leading to additional villages joining the Red Spear Society to defend themselves. The Red Spears' power and influence consequently grew greatly.[7] Meanwhile, the situation for the civilian population in eastern Shandong worsened due to the ascension of Liu Zhennian. Liu, a former subordinate of Fengtian warlord Zhang Zongchang, defected to the Nationalists during the Northern Expedition in 1928. In return, the new Nationalist government in Nanjing allowed him to keep the Shandong Peninsula as his personal fiefdom.[8][7] Liu's rule was marked by the brutality of his private army,[7] and high taxes[7] (though these taxes were still lower than those under the previous regime of Zhang Zongchang).[1] Furthermore, Liu did nothing to curb the widespread and escalating banditry. All this motivated additional peasants to join the Red Spears and the peasant movement to take a more aggressive stance against the perceived oppression by the government.[7]

Uprising

The situation began to escalate in late 1928, as the Red Spears organized a militant tax resistance, so that officials no longer dared to venture into areas held by the peasant movement such as Laiyang and Zhaoyuan.[7] The escalating Red Spears' revolt was helped by the deteriorating security in Shandong, as elements of Liu's army mutinied at Longkou and Huangxian in January 1929 and then fled into areas controlled by the Red Spears.[9] This mutiny was followed by a full-blown rebellion of demobilized ex-warlord troops led by Zhang Zongchang who wanted to regain control of Shandong. This insurgency devastated the northern Shandong Peninsula, as over 50 villages and six towns were destroyed by rebel troops. Both Zhang's followers as well as Liu's soldiers plundered, murdered and raped civilians, while captured women and girls were sold as slaves on Huangxian's market for 10–20 Mexican dollars[10][3][11] (the Mexican silver dollar was the main currency used in China at the time). This chaos allowed the Red Spears to further increase their power, as the desperate rural population flocked en masse to their cause in order to receive at least some protection from the rampaging soldiers and bandits.[3]

By the time Liu Zhennian managed to crush the warlord rebellion in summer 1929, the Red Spear Society had grown so powerful that it had set up a proto-state in Dengzhou county. There, it had established a headquarters, named a magistrate, taken over the local administration and introduced land as well as head taxes in order to fund itself.[3] In several other counties the peasant rebels at least prevented tax collection by government officials. The Red Spears also introduced compulsory membership to a certain degree, so that at least one member of every family in those villages the insurgents controlled had to be a Red Spear. Those among the rural population who worked at Zhifu were also forced to pay a special tax which was used by the Red Spears to buy weapons and ammunition.[3] Access to the insurgent areas was tightly controlled, and anyone wearing a government or military uniform was shot on sight. At this point, even those who did not speak the local dialect and therefore appeared to be outsiders, no longer dared to venture into the Red Spears' territory.[3] The peasant insurgents even came to behave like a mafia, looting, raping, robbing and kidnapping for ransom.[13] The victims of these activities mostly belonged to the wealthier upper class or were Christians, who consequently fled into the city of Dengzhou. As historian Lucien Bianco noted, secret societies in rural China had the "chronic tendency to degenerate into gangs", though at least some of the peasant rebels' criminal activities may have stemmed from military necessity.[13]

The number of Red Spears on the Shandong Peninsula had grown to about 50,000–60,000 in August 1929, and the peasant movement had thus become so strong that Liu Zhennian could no longer ignore them as he had done before. On 23 September, he launched an encirclement campaign between Dengzhou and Huangxian, pursuing a scorched earth policy to force the rebels into submission. His soldiers completely destroyed 18 villages and largely burned more than sixty others, killing all inhabitants they encountered, including women and children. By November, the Red Spears had ceased to exist in the area.[14]

Aftermath

Overall, once Liu had decided to finally take action, he had been able to crush the uprising relatively quickly and easily. According to Bianco, this was typical of rural rebellions at the time, which had only a chance to succeed as long as no concentrated action was undertaken against them by government representatives.[15] Despite continued challenges to his rule, Liu himself remained in power until he was defeated in a war with the ruler of western Shandong, Han Fuju, in 1932. Han was a relatively capable and popular civilian administrator, and his reign restored order and stability on the Shandong Peninsula.[16]

On the other side, many of those peasant rebels who had escaped or simply survived Liu's ruthless campaign found themselves with the official magistrate of Zhaoyuan. He gave the remaining Red Spears leaders jobs and enlisted the common fighters among the ex-insurgents into a local militia. This was an attempt to win them over, so that they would not resume their struggle against the authorities.[17]

References

- Department of State (1943), p. 141.

- Jowett (2017), p. 206.

- Bianco (2015), p. 6.

- Perry (1980), p. 153.

- Bianco (2015), pp. 4–6.

- Perry (1980), pp. 152–154.

- Bianco (2015), pp. 5, 6.

- Jowett (2017), pp. 45, 196, 197.

- Department of State (1943), pp. 140, 141.

- Jowett (2017), p. 197.

- Department of State (1943), pp. 142, 143.

- Bianco (2015), p. 9.

- Bianco (2015), pp. 6, 7.

- Bianco (2015), pp. 7, 8.

- Jowett (2017), pp. 206–208.

- Bianco (2015), p. 7.

Bibliography

- Bianco, Lucien (2015). Peasants without the Party: Grassroots Movements in Twentieth Century China. Abingdon-on-Thames, New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-1563248405.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bonavia, David (1995). China's Warlords. Hong Kong, Oxford, New York City: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Department of State (1943). Papers relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States 1929. Volume II. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Publishing Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jowett, Philip S. (2017). The Bitter Peace. Conflict in China 1928–37. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445651927.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perry, Elizabeth J. (1980). Rebels and Revolutionaries in North China, 1845-1945. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)